introduction

INTRODUCTION

Prepared by Leah F. Vosko, CPD Director

Welcome to the Comparative Perspectives on Precarious Employment Database (CPD). This online tool brings together a library of relevant and up-to-date sources in the field (including working papers), unique user-friendly statistical tables, and a thesaurus of concepts. Users can view and analyze its multidimensional tables to explore and compare the contours of precarious employment in thirty-three countries, including Australia, Canada, the United States, twenty-seven European Union (EU) member countries, and three non-EU member countries. The CPD is designed both for researchers and students. It also aims to be an interactive classroom teaching tool. This introduction provides basic information on the CPD’s conceptual approach to precarious employment in a comparative perspective, an explanation of our methodology, and an outline of the design principles behind the creation of harmonized variables used in many statistical tables. We encourage users to read this introduction first and then continue on to our interactive modules on forms of precarious employment, temporal and spatial dynamics, and health and social care.

PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT: A MULTIDIMENSIONAL APPROACH

Social actors and analysts have drawn upon the notion of “precariousness” since the 1970s to describe growing economic polarization and declining social protections, particularly in continental Europe (Bourdieu 1998; Castel 2006). In the social sciences, precarious employment refers to deficiencies in multiple forms of labour market security (Vosko et al. 2009). Underlying social science and policy interest in precarious employment is an understanding that substantial changes have occurred in the normative model of employment in many countries – or customs, conventions and governance mechanisms linking the organization of work and the labour supply (Deakin 2002).

For much of the twentieth century, the standard employment relationship (or SER) served as the normative model of employment (See Leighton 1986; Mückenberger 1989; Rodgers 1989; Büchtemann and Quack 1990; Tilly 1996; Fudge 1997; Fudge and Vosko 2001a; 2001b; Bosch 2004). The SER refers to a situation where a worker has one employer, works for a standardized working time (i.e., 8 hours a day, 40 hours a week, assuming leaves and holidays with pay), is employed continuously (i.e., year-round) on the employer’s premises under direct supervision, enjoys extensive statutory entitlements and social benefits, and expects to be employed indefinitely (Mückenberger 1989; Schellenberg and Clark 1996; Fudge 1997; Vosko 1997, 2009; Bosch 2004).

The SER is linked to practices and institutions that determine the organization of social reproduction, that is the daily and intergenerational reproduction of the working population (for a helpful review of distinct approaches to social reproduction see, Picchio 1992; Clark 2000; Bezanson and Luxton 2006). The organization of social reproduction is shaped by a gender contract, forming the normative and material basis around which sex/gender divisions of paid and unpaid labour operate in a given society (Rubery 1998; cf. Pfau-Effinger 1999). The normative gender contract associated with the SER assumed a “male breadwinner” who earned a family wage in the public sphere and a “female caregiver” who performed unpaid care work in the private domain of the home, accessing social benefits through her spouse (Rubery 1998; Fudge and Vosko 2001a; see Gottfried 2009 on the related notion of a reproductive bargain). Despite the exclusion of many kinds of work and groups of workers from the SER, social benefits and protections were organized around it for much of the twentieth century. In industrialized countries, the SER was and continues to be racialized, albeit differentially: for example, working class women of colour and immigrant women were largely excluded from this employment norm as both women holding responsibilities for unpaid domestic labour in their own households and communities and low-wage workers, many of whom perform tasks associated with social reproduction in the market (see Arat-Koc 1989; Glenn 1997; Zeytinoglu 2000; Cranford and Vosko 2006; McKay 2008). Racialized men have also faced marginalization from the SER both as “minority” populations (e.g., Roediger 1999) and as immigrants (e.g., Bauder 2006; McKay 2008). Access to entitlements and protections under the SER was also (and continues to be) linked to national citizenship, contributing to forming a class of workers who are excluded from many of the rights guaranteed by the SER by virtue of their immigration status (Vosko 2010).

Problems with Common Conceptualizations

Since the 1970s, most OECD countries have experienced substantial increases in one or more of the following forms of employment (i.e., different categories of paid/wage work) and work arrangements: self-employment, homework, on-call employment, part-time employment, or temporary employment (ILO 1999). This trend is correlated with women’s rising participation in paid work, the growth of international migration for employment, and a tendency towards declining job quality for women and men (Standing 1999). In different places, the latter trend is identified as the growth of “atypical” (Europe, e.g., Council of Europe 1985), “non-standard” (Canada, e.g., Economic Council of Canada 1990; Krahn 1991 and 1995), “contingent” (US, e.g., Polivka and Nardone 1989 and 1996) or “precarious” (Europe, e.g., Rodgers and Rodgers 1989) employment. Many studies erect a simple dichotomy organized around the form of employment. Precarious employment is equated with temporary or fixed-term contracts and is assumed to be less secure, while a permanent, full-time job is assumed to be secure and de facto not precarious. This one-dimensional approach does not capture the dynamics of changing employment relationships within or across countries. It also obscures the diversity of forms of employment that exhibit dimensions of labour market insecurity, often including full-time permanent jobs. Indeed, declining union membership and falling real wages and benefit levels have led to the erosion of full-time ostensibly permanent employment in many OECD countries. However, the character of this change is different in different places: while many countries in Western Europe, Canada and Australia have experienced an overall decline in the number of full-time permanent jobs, the US has seen a drastic decline in the quality of these jobs (see Vosko 2010; for country case studies, see also Campbell 2002; and Stone 2004; and Carré and Heintz 2009 on the US).

Dimensions of Labour Market Insecurity

In contrast, our conceptualization of precarious employment builds on a growing body of scholarship that takes a multidimensional approach to precarious employment (Rodgers 1989; Laparra et al. 2004); Vosko 2000, 2006; Barbier 2005). Overcoming a simple dichotomy between “standard” and “non-standard” jobs and the conflation of the former with job security and the latter with job insecurity, our approach assumes that any job – regardless of its form – can be precarious. To understand the nature of job insecurity, the CPD focuses on four “dimensions of labour market insecurity” (Rodgers 1989): degree of certainty of continuing employment; regulatory protection; control over the labour process and income level.

1. Degree of Certainty addresses the situation of employed workers who face short-term work contracts or risk of termination (Rodgers 1989). It is also a key dimension of precariousness for self-employed workers (Cranford et al. 2005) whose work is mediated by commercial relationships and often involves performing services for multiple “customers,” a situation that can result in numerous short-term employment relationships (Vosko 2006).

2. Regulatory Protection addresses whether laws and policies are both applicable to workers in need of protection and enforceable. This dimension includes not only protection of working conditions through regulated and enforceable labour standards, but also employment benefits (statutory and social) often linked to the employment relationship such as pensions and unemployment insurance (Bernstein et al. 2006; Vosko 2006).

3. Control over the Labour Process refers to workers’ power over how work is organized and executed. This dimension is affected by membership in a union and/or coverage under a collective agreement among those in employment relationships (Jackson 2003; Anderson et al. 2006). It is also shaped increasingly by membership in an association among self-employed workers (e.g., professional associations; farmers’ unions).

4. Income Level concerns the total direct and indirect income that workers receive in exchange for the sale of their labour power. It includes wages for employees and payments received by the self-employed, government transfers, and government- and employer-sponsored benefits.

These four core dimensions that we focus on in the CPD are far from exhaustive. For example, as the health and social care module illustrates, the availability of social services and the form of their delivery (public or private) is also key. We have nevertheless selected them for two reasons; first, their inclusion aims to reflect existing scholarly literature on dimensions of labour market insecurity (see e.g., Rodgers and Rodgers eds. 1989; Vosko, MacDonald and Campbell eds. 2009; Laparra et al. 2004). Second, given the well-documented limitations of statistical data sources (see below), the inclusion of these dimensions (and exclusion of others) reflects the degree to which particular aspects of precariousness can be explored comparably with statistical data available through labour force and household surveys. Where appropriate, particular modules may incorporate other dimensions germane to their central theme – e.g., dimensions related to occupational health and safety are explored in the health and social care module.

PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

This rise of precarious employment tells us little about how forms of employment and dimensions of labour market insecurity relate. The CPD employs a comparative approach to explore how precarious employment is shaped by particular regulatory contexts, by the social location of workers, by occupation and industry, and by uneven geographies of capitalism. Despite claims of a globalizing world that flattens social and spatial differences (e.g., Ohmae 1990), the CPD reveals both variations and commonalities in precarious employment, the contours of which can inform policy-relevant research and action (Kittay, Jennings and Wassuna 2005).

Dimensions that constitute precariousness in employment are shaped by the regulatory context. Historical and current policy choices and associated legislative frameworks relating to the labour market as a whole and the industrial relations system specifically matter. So too do employment and social policies, which may be applied differently to workers in different phases of the life course. Further, it is not just the design of policies that makes a difference, but also their application and enforcement. Differences in the regulatory context viewed at the national level shape precarious employment in different ways in different countries. Let’s take the EU as an example. Despite the fact that its twenty-seven member countries have agreed to pursue a common employment policy (known as the European Employment Strategy), national policies and institutional structures are responsible for significant variation in job quality within Europe (Davoine, Erhel and Guergoat-Lariviere 2008).

Regulatory context is not only differentiated at the subnational, national, and supranational scale, however. Labour and social protections, and their meanings, can differ within nation states. In Canada, for example, minimum labour standards are largely a provincial matter since the Federal Labour Code covers only 10 percent of all workers, leading to varied levels and modes of regulatory protection across provinces. Moreover, the scale of regulation is itself not fixed: over the last thirty years, we have witnessed a “re-scaling” of regulation (see Swyngedouw 1997; Brenner 1999) both to supra-national bodies like the EU and to local governments (municipal, provincial, etc.). Measuring the import of these shifts and their impacts on dimensions of precarious employment is difficult; nevertheless, it is important to recognize both differences between countries (the unit of analysis for many labour force and household surveys and therefore elevated in the CPD), and to consider regulatory variation and conformity at a variety of spatial scales. Citations in the CPD library aim to bring the latter processes into focus to enrich interpretations of statistical data. The temporal and spatial dynamics module addresses, in part, sub-national and supranational patterns of precarious employment.

It is well-established that social location – particularly inequalities along the lines of socially-constructed differences such as gender, nationality, race, ethnicity, (im)migrant status, (dis)ability and age – shape patterns of precarious employment across, as well as within, subnational, national and supranational jurisdictions (e.g., Bakan and Stasiulis 1997; Zeytinoglu and Muteshi 1999; Burri 2004; see also contributions to Vosko, MacDonald and Campbell eds. 2009; Vosko 2010). In general, workers in precarious jobs belong disproportionately to social groups marginalized through practices of racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression. Who faces a marginalized position in the labour market is further shaped by colonial and postcolonial trajectories, as well as historic forms of inequality within macro-regions and nation-states (McDowell 2008). For example, migrants from formerly colonized and/or exploited parts of the global South are often concentrated in the lower rungs of the labour market in the global North (see for e.g., Jonsson and Nyberg 2009). Comparative analysis must take into account these particular differences. However, many countries either do not collect or do not release data on socially constructed ethnic and/or racial categories, making it difficult, if not impossible, to study precarious employment comparatively through the lenses of race/ethnicity using national surveys. In the CPD, all tables do allow for sex-based analysis. Where possible, the CPD also includes comparative indicators for immigrant status to allow users to consider how entry category or form of immigration shapes and is shaped by precarious employment across different countries.

Comparative analyses are also enriched by attention to industrial and occupational patterns and trends, which can tell us much about economic restructuring and its impacts on marginalized groups who tend to be segregated along such lines. The challenge of industry and occupational analysis is related to restructuring itself. Whereas industry traditionally referred to the products of workers’ labour power and occupation referred to what people did at work, new definitions in many national surveys redefine industry in terms of the type of employer rather than the product of work. This shift reflects and reinforces the trend towards contracting out services in both the public and the private sectors, leading to an increasing number of jobs in lower-tier “service industries.” A significant proportion of growth in the service industry of many high income countries does not indicate a change in where people work but rather who they work for when they do the same kind of job. Such service industries, while associated with increased precarity, are defined in ways that make it difficult to trace trends in labour market insecurity. By crossing industry by occupation, however, we can get a clearer picture of how segregation of women, immigrants, and racialized groups along these lines, and the accompanying precarity, functions. Mapping these categories and their relationship to social location across nation states is difficult. Yet cross-national comparisons can reveal sectors and occupations where precarious employment is more common and distinct patterns in precarity in sectors vulnerable to restructuring (see for e.g., Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008). The CPD undertakes this type of analysis through the lens of health and social care. This sector, concentrating large numbers of women paid workers, provides a lens through which to understand dynamics of restructuring in relation to precarious employment across CPD countries.

Intersecting with regulatory context, social location, and industry and occupation, what we call uneven geographies of capitalism broadly shape how precarious employment is manifest in difference places. Historic and contemporary patterns of production and social relations – including diverse histories of colonialism as well as class and anti-colonial struggle – structure the position of countries, localities and macro-regions in uneven relations to one another (Amin 1976; Harvey 1982; Massey 1984; Sheppard 2002). The contours of deindustrialization, new patterns of production organization, gendered and racialized exploitation, and increasingly deregulated capital flows have reshaped and, many scholars argue, have intensified these uneven geographies over the last forty years (e.g., Arrighi 1994; Harvey 2003). These uneven geographies contribute to considerable variation in precarious employment across different places.

The CPD allows users to examine precarious employment in a subset of countries, many of which share a structurally dominant position in the global economy. CPD countries are also characterized by considerably high levels of industrialization in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries and developed institutions associated with the welfare state. In addition to these structural similarities, the country or subset of countries under examination benefits from commensurable systems of labour force measurement and documentation easily accessible in the English language (see Data Sources below). Our choice of countries stems from these structural similarities and practical concerns (i.e., availability of data). Yet, in building the tool, participating researchers recognize that precarious employment is an important area of research in the global South and in industrial powers of East Asia (Gottfried 2009; Jihye Chun 2009). In the global South, precarious employment is increasingly associated with the so-called “informal economy” (or forms of paid work unregulated by formal laws), as well as the erosion of labour standards and their non-enforcement (Portes 1989; Itzigsohn 2000; Kudva and Beneria 2005). While the CPD does not currently contain statistical tables incorporating countries outside of its 33 country subset, its conceptual guides, library and thesaurus offer the user some ways to consider connections between precarious employment in the global North and the global South.

THE LIBRARY

The CPD library is a searchable citation database of highly relevant theoretical and empirical works including working papers, books, book chapters, journal articles, government documents, and statistical tables. The library is fully integrated with other CPD tools, allowing users to gain greater understanding for the conceptual guides and the statistical tables. Metadata comprising each citation include expert keywords, allowing users to explore the material through simple keyword searching, field searching or complex Boolean searching.

The CPD includes a tutorial on how to use the library.

THE THESAURUS

Serving as a bridge between the library and statistical components, the thesaurus identifies core concepts derived from scholarship on precarious employment. The thesaurus has four central functions. First, it provides a controlled vocabulary for searching the library, helping researchers link the statistical tables and the library resources. Its second function is descriptive—that is, it describes the language of the field, and illustrates relationships between terms, concepts and ideas. Its third function is to facilitate comparison across national states given the diversity of terms that can be used to describe similar phenomena and the use of the same term to mean different things in different contexts. The thesaurus provides country-level descriptors to assist the reader in researching precarious employment at multiple levels and across nation states. Finally, its fourth function is prescriptive in that it seeks to communicate how creators of the CPD understand certain ideas, and the connections between them.

The CPD includes a tutorial on how to use the thesaurus.

STATISTICAL TABLES

Statistical tables allow for a comparative analysis of precarious employment across different nation states. Researchers can explore in-depth the manifestations of precarious employment in different places and how these relate to workers’ social locations – including sex/gender, citizenship and age. The tables are meant to be used together with the thesaurus of concepts, library of resources, this introduction, as well as the three CPD conceptual guides. The latter include descriptions of variables that proxy, or stand-in for, dimensions of precariousness and social relations.

Inquiring into a multidimensional phenomenon such as precarious employment in different places and contexts, at different scales, over different phases of the life course raises fundamental questions about comparison. Some questions are practical – for example, what forms of employment or dimensions of labour market security, and social locations, and geographies is it possible to measure in available statistical surveys? Other questions are conceptual, and indeed normative. Is it justifiable to compare different forms and dimensions of precarious employment sharing similar attributes? If not, what are the appropriate modes of comparison?

In response to these types of questions, where possible, the CPD attempts to provide statistical tables containing variables reflecting national definitions and a variety of harmonized variables (i.e., harmonized to various degrees), that is, variables integrating existing data from different surveys such that the data are reshaped to become comparable across countries (Clement and Prus 2004).

Principles of Harmonization

In constructing statistical tables to explore precarious employment in a comparative perspective, we build on the insights of scholarly literature from several disciplines that explore the phenomenon through multiple methods (qualitative, quantitative, archival, and policy research, etc.). The CPD subscribes to five principles of harmonization.

1. Practicality – Do the data exist? Can they be compared? This principle reflects issues surrounding whether certain questions are asked by a given survey or set of surveys, how they are asked, missing (and available) data for particular years and/or places, and the categories derived from a given question or set of questions by those who design and conduct surveys.

2. Comparability, but not at any price – This principle reflects the aim to compare likes with likes by considering the meanings of categories in context. For example, scholarship illustrates a correspondence between casual work in Australia and temporary employment in Canada and the EU 27 (Campbell and Burgess 2001) despite an apparent difference in categorization. The CPD aims to reflect these important nuances and differences in the cross-national and regional comparisons its tables facilitate.

3. Meaningful classifications – Many surveys appear to provide information on the same topics. However, it can be difficult or impossible to compare such information in a meaningful way across multiple nation states and/or at different scales. One common example is level of educational attainment. Educational systems differ across the contexts under consideration such that different social meanings are attached to the same or similar credentials in different places and some forms of educational attainment do not exist in certain places, such as apprenticeships. As a result, in some instances, it may be misleading to attempt comparison. Another example is firm-size, often used as an indicator of control over the labour process, but which can have different legal implications in different regulatory contexts, tied especially to regulatory frameworks governing employment relationships. Finally, there is the vexed issue of creating comparable occupational and industrial classifications; this issue is addressed in-depth in the module on health and social care.

4. Maintaining the smallest level of granularity – When the goal is comparison, researchers are confronted with the inevitable trade-off between comparability and finely-grained analysis. To address this trade-off, every CPD table aims at the smallest level granularity by maximizing the level of detail provided in the tables.

5. Pointing to silences/invisibilities in the data – Drawing on feminist political economy, the CPD attempts to expose the ways in which a great deal of labour performed mostly by women is not counted by governments in, for example, measures of gross domestic product (Waring 1988; Picchio 1992), nor is the often invisible contribution of groups such as undocumented migrants, a growing population in many OECD countries (Samers 2001). Standardized categories of occupation and industry, furthermore, miscount feminized labour. These and other elements of invisibility are represented in the database in several tables that include empty cells, a product of the gendered and racialized politics of how work is and is not counted. We also build upon this theme in the CPD modules and in the library resource.

DATA SOURCES

The CPD’s multidimensional comparative and nation- and region-specific tables draw on data from seven sources.

The European Union Labour Force Survey (EU LFS)

The EU LFS is a quarterly rotating sample survey covering the population in private households in the EU, European Free Trade Area (except Lichtenstein) and Candidate Countries. It provides quarterly results of workforce participation for people aged 15 years and above. The sample size is approximately 1.7 million (in 2004). The EU LFS micro data collection starts in 1983. Each national statistical agency is responsible for selecting the sample, preparing the questionnaires, conducting the direct interviews among households, and forwarding the results to Eurostat following a common set of protocols. The main statistical objective of the Labour Force Survey is to divide the population of working age (15 years and above) into three mutually exclusive and exhaustive groups – persons in employment, unemployed persons and inactive persons – and to provide descriptive and explanatory data on each of these categories. Respondents are assigned to one of these groups on the basis of the most objective information possible obtained through the survey questionnaire, which relates principally to their actual activity within a particular reference week.

The EU European Community Household Panel (ECHP) and the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (SILC)

The EU ECHP was conducted in 14 EU member states (EU 15 minus Sweden) from 1994 to 2001 and was replaced by the EU SILC in 2004. The EU SILC is conducted in the EU 28 (plus Norway, Iceland and Switzerland) and has a sample size of slightly more than half a million. The purpose of both surveys is to provide measures on income distribution and social exclusion comparable across EU member states. The EU SILC has both a longitudinal and a cross-sectional component. Longitudinal data pertaining to individual-level changes over time are observed periodically over a four year period. Cross-sectional data contain variables on income, poverty, social exclusion and other living conditions. Like most household surveys, both the ECHP and the SILC only cover people living in private households and exclude collective households and institutionalized populations.

The Household Income and Labor Dynamics of Australia (HILDA)

The HILDA is an Australian household-based panel study conducted on an annual basis since 2001 based at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research, University of Melbourne. Each wave of the survey consists of approximately 7,500 households and 20,000 individuals and longitudinal data are available (i.e., the same people are interviewed over several waves). The survey collects information about economic and subjective well-being, labour market dynamics, and family dynamics.

The United States Current Population Survey (CPS)

The US CPS is a monthly survey of about 50,000 households conducted by the US Census Bureau and US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The survey has been conducted for more than 50 years. The CPS is the primary source of information on labour force characteristics of the US population. The sample is scientifically selected to represent the civilian non-institutional population. Respondents are interviewed to obtain information about the employment status of each member of the household 15 years of age and older although published data covers only those aged 16 and over. Labour statistics from the CPS include employment, unemployment, earnings, hours of work, and other indicators. These are available by a variety of demographic characteristics including age, sex, race, marital status, and educational attainment. They are also available by occupation, industry, and class of worker. Supplemental questions to produce estimates on a variety of topics including school enrollment, income, previous work experience, health, employee benefits, and work schedules are also often added to the regular CPS questionnaire.

The Canadian Labour Force Survey (CA LFS)

The CDN LFS is a monthly survey administered by Statistics Canada since 1976. The survey sample size is approximately 54,000 Canadian households. It excludes people living in institutions, persons under 15, and residents of First Nations reservations. The CDN LFS gathers data primarily concerning standard labour market indicators such as employment status, industry and occupation indicators, wages, union status, job permanency, workplace size, and a variety of traditional personal demographic characteristics.

The Canadian Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID)

The SLID is a household survey conducted by Statistics Canada since 1993. The survey excludes residents of the Yukon, the NWT, Nunavut, persons living on First Nations reservations, and institutionalized populations. The survey contains both a cross-sectional and a longitudinal component. The cross-sectional component is considered the most detailed source of data on income for Canada and also provides additional variables that supplement the Canadian LFS. The longitudinal component follows a total of 15,000 households (sampled from the LFS) over six years in two cohorts (i.e., a new cohort is phased in every three years). The longitudinal component provides a range of information related to transitions, durations, and repeat occurrences related to respondents’ financial and work situations, as well as extensive information on family situation, education, and demographic background.

COMMON INDICATORS: THE HARMONIZED CODEBOOK + DATA DICTIONARY

The key to the available variables, and their definitions, in the CPD is the harmonized codebook + data-dictionary. Created by CPD experts, this codebook contains a listing of all the variables available in the statistical tables, accompanied by an explanation of the delineation of each variable, the mapping processes used to harmonize that variable and the algorithm designed to implement that mapping. The harmonized codebook + data dictionary is a living document, constantly changing in response to new data discoveries and researcher insight. Please refer to it frequently when working with the CPD multidimensional tables.

A number of indicators are common to nearly all the CPD tables. These variables include age, sex, country, and year. All tables also include a weight, thereby allowing for a maximum of four additional indicators in each table.

There are several breakdowns of these variables available in the CPD harmonized codebook, each of which is designed to meet different research needs.

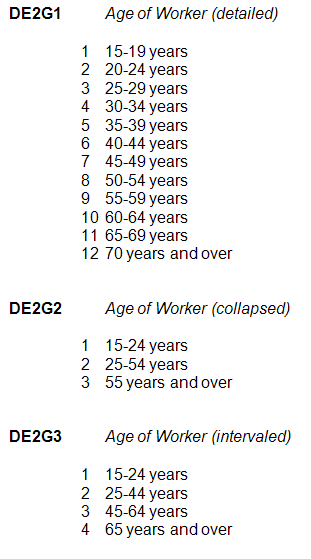

A good example of a common variable is age, which can be delineated quite specifically or broadly depending on the nature of the research question. The following list includes three examples of how age can be measured in CPD tables across the modules.

The first variable is the most detailed, the second is the least detailed, and the third is relatively detailed; consequently, a user less interested in detailed age breakdowns and concerned to look in depth at other variables may wish to select a table including DE2G3 whereas a user concerned centrally with age may opt to examine DE2G1.

In addition to age, sex, country, and year, many CPD statistical tables include the variable for form of employment given its centrality to the study of precarious employment, as described above. This variable is available in several different breakdowns discussed at greater length within the conceptual guide to the forms of precarious employment module. Conceptual guides to each of the modules, another central feature of the architecture of the CPD, aim to acquaint users with indicators common to a given module.

THE MODULES: A RATIONALE

As noted above, the CPD includes three modules on (1) forms of precarious employment, (2) temporal and spatial dynamics, and (3) health and social care, each of which is organized around a set of research questions presented and elaborated in a conceptual guide. These modules are not meant to be comprehensive; rather, they provide different entry points to explore themes of precarious employment in comparative perspective.

Forms of Precarious Employment

The aim of the forms of precarious employment module is to enable researchers to probe how form of employment relates to precariousness in different places. Overcoming the dichotomy between “standard” and “non-standard” jobs and the tendency to treat precariousness as synonymous with the latter, its point of departure is that all employment forms should be examined in relation to dimensions of labour market insecurity (described above). The module draws on research highlighting the significance of the growth of forms of employment such as part-time and temporary paid employment and solo self-employment in many contexts while also revealing the heterogeneity of so-called non-standard employment across nation states and at multiple scales. In addition, it enables users to explore dimensions of labour market insecurity within the closest proxy for the SER (i.e., full-time permanent employment). The module also places an emphasis on allowing users to track cross-national and regional variations between social location, and form of employment, as well as the effects of particular forms on worker well-being.

Temporal and Spatial Dynamics

The temporal and spatial dynamics module allows for gender sensitive analysis of precarious employment incorporating the movement of people through time, space and over the life course. Encouraging researchers to extend the analyses of labour market insecurity beyond a particular time and place, the module permits an exploration of variations in the organization and distribution of its dimensions and worker (im)mobility that occur within and between countries. The module also aims to facilitate scholarship addressing similarities and differences related to the permanence of precarious employment along with patterns of unemployment, underemployment, and inactivity in comparative perspective.

Health and Social Care

The health and social care module endeavors to look at the variations in the distribution of health and social care across and within countries over time. Everywhere health and social care are primarily women’s work. And much of this care remains hidden, under or unpaid, precarious and uncounted. The challenges of this module are to bring the nature of this care work and the conditions of employment of those providing it into focus. The module does so by first defining care and then developing the notion of care context, which encompasses the rights and responsibilities of governments and individuals in the provision of care as well as the specific models of care and the role of medicine and women within them (Kittay et al. 2005). The module attempts to highlight differences in definitions and models of health and social care, while also creating mappings providing opportunities for comparative research.

Through its contents, the HSC module allows researchers to capture some of the variation and some of the consequences of new labour market developments in the health and social care sector. Although it remains necessary to keep the assumptions about women’s “innate” capacities and “skills” in mind when developing comparisons, it is also necessary to attend to the structural constraints on their work and to the relationship between paid and unpaid work. The data used in studying health and social care are quite complex. It is important to look at the similarities among women’s involvement in care. Following Stone (2000), module experts call this lumping. In addition, it is important to remember that there are significant differences among women in relation to their social, economic, geographic and other locations. Glucksman (2000: 16) talks about “slicing” data to create multiple and complex pictures of particular people in particular places in ways that recognize profound inequities. It is critical to remember that much is obscured about both differences and inequalities when researchers focus on patterns for women as a group given the differences among women that are difficult to capture with the data limitations. CPD module experts like to think of these limitations in the data as “silences” requiring us to ask continually who and what is missing from the picture we are able to create using data sources available. The “noises” are created by the availability and construction of the data, shaping what researchers can see and how we can see it. So, for example, work in the health and social care sector is currently primarily defined in terms of occupations and industry, drawing on classificatory schemes that make significant (often androcentric and ethnocentric) assumptions about private and public divisions and responsibilities.

WORKS CITED

Amin, S., and Pearce, B. (1976). Unequal Development: An essay on the Social Formations of Peripheral Capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Anderson, J., Beaton, J., and Laxer, K. (2006). “The Union Dimension: Mitigating Precarious Employment?” In L. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 301-317).

Arat-Koc, S. (1989). “In the Privacy of our own Home: Foreign Domestic Workers as Solution to the Crisis in the Domestic Sphere in Canada”. Studies in Political Economy, 28 (Spring), 33-58.

Armstrong, P., Armstrong, H., and Scott-Dixon, K. (2008). Critical to Care: The Invisible Women in Health Services. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Arrighi, G. (1994). The Long Twentieth Century. London and New York: Verso.

Bakan, A. B., and Stasiulis, D. (1997). “Foreign Domestic Worker Policy in Canada and the Social Boundaries of Modern Citizenship”. In A. B. Bakan and D. Stasiulis (Eds.), Not One of the Family: Foreign Domestic Workers in Canada. (pp. 29-52). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Barbier, J. (2005). “La Précarité: Une Catégorie Française à L’épreuve de la Comparaison Internationale”. Revue Française De Sociologie, 46(2), 351-371.

Bauder, H. (2006). Labor Movement: How Migration Regulates Labor Markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berstein, S., Lippel, K., Tucker, E., and Vosko, L. (2006). “Precarious Employment and the Law’s Flaws: Identifying Regulatory Failure and Securing Effective Protection for Workers”. In L. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 203-220).

Bezanson, K., and Luxton, M. (2006). Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neo-liberalism.

Bosch, G. (2004). “Towards a New Standard Employment Relationship in Western Europe”. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 42(4), 617-636. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2004.00333.x

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Contre-feux: Propos pour Servir à la Résistance contre L’invasion Néo-libérale. Paris: Editions Raison D’agir.

Brenner, N. (1999). “Beyond State-Centrism? Space, Territoriality, and Geographical Scale in Globalization Studies”. Theory and Society, 28(1), 39-78.doi:10.1023/A:1006996806674

Büchtemann, C. F., and Quack, S. (1990). “How Precarious is ‘Non-standard’ Employment? Evidence for West Germany”. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 14(3), 315-329. doi:90/090315+15 803.00/0

Burri, S. (2004). “Indirect Sex Discrimination in Pay and Working Conditions: The Application of a Potentially Dynamic Concept”. The Third Experts’ Meeting, Hosted by the Dutch Equal Treatment Commission.

Campbell, I., and Burgess, J. (2001). “Casual Employment in Australia and Temporary Work in Europe: Developing a Cross-national Comparison”. Work, Employment & Society, 15(1), 171-184. doi:10.1017/S0950017001000083

Campbell, I. (2002). “Extended Working Hours in Australia“. Labour & Industry, 13 (1): 91-110.

Carré, F., and Heintz, J. (2009). “The United States: Different Sources of Precariousness in a Mosaic of Employment Arrangements”. In L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald and I. Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment (pp. 43-59). London and New York: Routledge.

Castel, R. (2006). “Et maintenant, le ‘précariat'”. Le Monde.

Chun, J. J. (2009). “Legal Liminality: The Gender and Labour Politics of Organizing South Korea’s Irregular Workforce”. Third World Quarterly, 30(3), 535-550. doi:10.1080/01436590902742313

Clark, L. (2002). “Disparities in Wage Relations and Social Reproduction”. In L. Clarke, P. de Gijsel and J. Janssen (Eds.), The Dynamics of Wage Relations in the New Europe. (pp. 134-138). Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Clark, P. F., and Clark, D. A. (2003). “Challenges Facing Nurses’ Associations and Unions: A Global Perspective”. International Labour Review, 142(1), 29-47. doi:10.1111/j.1564-913X.2003.tb00251.x

Clark, K., and Drinkwater, S. (2000). “Pushed out or Pulled in? Self-employment Among Ethnic Minorities in England and Wales”. Labour Economics, 7(5), 603-628. doi:10.1016/S0927-5371(00)00015-4

Clement, W., and Prus, S. (2004). The Vocabulary of Gender and Work: Some Challenges and Insight from Comparative Research. Unpublished manuscript.

Cranford, C., Fudge, J., Tucker, E., and Vosko, L. F. (Eds.). (2005). Self-employed Workers Organize: Law, Policy, and Unions. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Cranford, C., and Vosko, L. F. (2006). “Conceptualizing Precarious Employment: Mapping Wage Work Across Social Location and Occupational Context”. In L. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 43-66). Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Council of Europe (1985). Temporary Employment Businesses: General Problems, Specific Problems Relating to Legal or Illegal Hiring out of Workers Across Borders. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

Davoine, L., Erhel, C., and Guergoat-Lariviere, M. (2008). “Monitoring Quality in Work: European Employment Strategy Indicators and Beyond”. International Labour Review, 147(2-3), 163-198.

Deakin, S. (2002). “The Many Futures of the Contract of Employment”. In J. Conaghan, R. M. Fischl and K. Klare (Eds.), Labour Law in an Era of Globalization: Transformative Practices and Possibilities. (pp. 177-196). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Economic Council of Canada. (1990). Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: Employment in the Service Economy. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada.

Fudge, J. (1997). Precarious Work and Families. Toronto: Centre for Research on Work and Society, York University.

Fudge, J., and Vosko, L. F. (2001a). “Gender, Segmentation and the Standard Employment Relationship in Canadian Labour Law and Policy”. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 22(2), 271-310. doi:10.1177/0143831X01222005

Fudge, J., and Vosko, L. F. (2001b). “By Whose Standards? Re-regulating the Canadian Labour Market”. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 22(3), 327-356. doi:10.1177/0143831X01223002

Glenn, E. N. (1997). “Citizenship Today: The Contemporary Relevance of T.H. Marshall (review)”. Contemporary Sociology, 26(4), 460-462.

Glucksmann, M. A. (2000). Cottons and Casuals: The Gendered Organization of Labour in Time and Space. London: Routledge-Cavendish.

Gottfried, H. (2009). “Japan: The Reproductive Bargain and the Making of Precarious Employment”. In L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald and I. Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. (pp. 76-91). New York: Routledge.

Harvey, D. (1982). Limits to Capital. London: Verso.

Harvey, D. (2003). The New Imperialism. New York: Oxford University Press.

ILO. (1999). Report of the Director General: Decent Work. Geneva: International Labour Office.

Itzigsohn, J. (2000). Developing Poverty: The State, Labor Market Deregulation, and the Informal Economy in Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Jackson, A. (2003). In Solidarity: The Union Advantage. Research paper #27. Ottawa: Canadian Labour Congress.

Jonsson, I., and Nyberg, A. (2009). “Sweden: Precarious Work and Precarious Unemployment”. In L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald and I. Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. (pp. 194-210). London and New York: Routledge.

Kittay, E. F., Jennings, B., and Wasunna, A. A. (2005). “Dependency, Difference and the Global Ethic of Longterm Care”. The Journal of Political Philosophy, 13(4), 443. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9760.2005.00232.x

Krahn, H. (1991). Non-standard Work Arrangements. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 3(4), 35-45.

Krahn, H. (1995). Non-standard Work on the Rise. (No. Cat. 75-001E). Statistics Canada.

Kudva, N., and Beneria, L. (2005). “Rethinking Informalization: Poverty, Precarious Jobs and Social Protection”. Rethinking Informalization in Labor Markets, Cornell University.

Laparra, M., Barbier, J., Darmon, I., Düll, N., Frade, C., Frey, L.,Vogler-Ludwig, K. (2004). Managing Labour Market Related Risks in Europe: Policy Implications. European Commission, DG Research, V Framework Programme.

Leighton, P. (1986). “Marginal workers”. In R. Lewis (Ed.), Labour Law in Britain. (pp. 509-512). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Massey, D. B. (1984). Spatial Divisions of Labor: Social Structures and the Geography of Production. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

McDowell, L. (2008). “Thinking Through Work: Complex Inequalities, Constructions of Difference and Trans-national Migrants”. Progress in Human Geography, 32(4), 491-507. doi:10.1177/0309132507088116

McKay, S. (2008). Refugees, Recent Migrants and Employment: Challenging Barriers and Exploring Pathways. New York and London: Routledge.

Mückenberger, U. (1989). “Der wandel des normalarbeitsverhältnisses unter bedingungen einer krise der “Normalität””. (The Change of the Standard Employment Relationship under the Conditions of a Crisis of “Normality”). Gewerkschaftliche Monatshefte, 4, 211-223.

Ohmae, K. (1990). The Borderless World: Power and Strategy in the Interlinked World Economy. New York: Harper Business.

Pfau-Effinger, B. (1999). “Change of Family Policies in the Socio-cultural Context of European Societies”. Comparative Social Research, 18, 135-160.

Picchio, A. (1992). Social Reproduction: The Political Economy of the Labour Market. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press. doi:0521 41872 0

Polivka, A. E. (1996). “Contingent and Alternative Work Arrangements, Defined”. Monthly Labor Review, 119(10), 3-9.

Polivka, A., and Nardone, T. (1989). “On the Definition of “Contingent Work””. Monthly Labour Review, 112(12), 9-16.

Portes, A., Castells, M., and Benton, L. A. (1989). “The Policy Implications of Informality”. In A. Portes, M. Castells and L. A. Benton (Eds.), The Informal Economy: Studies in Advanced and Less Developed Countries. (pp. 298-311). The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Rodgers, G. (1989). “Precarious Work in Western Europe: The State of the Debate”. In G. Rodgers, and J. Rodgers (Eds.), Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. (pp. 1-16.). Belgium: International Institute for Labour Studies.

Rodgers, G., and Rodgers, J. (1989). Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. Brussels: International Institute of Labour Studies.

Roediger, D., Davis, M., and Sprinker, M. (1999). The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (2nd ed.). New York and London: Verso.

Rubery, J. (1998). Women in the Labour Market: A Gender Equality Perspective. Paris: OECD Directorate for Education, Employment, Labour and Social Affairs.

Samers, M. (2001). “Here to Work: Undocumented Immigration in the United States and Europe”. SAIS Review, xxi(1), 131-145. doi:DOI: 10.1353/sais.2001.0022

Schellenberg, G., and Clark, C. (1996). Temporary Employment in Canada: Profiles, Patterns and Policy Considerations. (No. 507). Ottawa: Centre for the Study of Living Standards.

Sheppard, E. (2002). “The Spaces and Times of Globaliztion: Place, Scale, Networks and Positionality”. Economic Geography, 78(3), 307-330. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2002.tb00189.x

Standing, G. (1999). Global Labour Flexibility. Groundsmill: St. Martin’s Press.

Stone, D. (2000). “Caring by the Book”. In M. H. Meyer (Ed.), Care Work and Gender Labour and the Welfare State. (pp. 89-111). London: Routledge.

Stone, K. V. W. (2004). From Widgets to Digits: Employment Regulation for the Changing Workplace. Cambridge, UK.: Cambridge University Press.

Swyngedouw, E. (1997). “Neither Global nor Local: ‘Glocalization’ and the Politics of Scale”. In K. Cox (Ed.), Spaces of Globalization: Reasserting the Power of the Local. (pp. 137-166). New York: Guilford.

Tilly, C. (1996). Half a Job: Bad and Good Part-time Jobs in a Changing Labour Market. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Vosko, L. F. (1997). “Legitimizing the Triangular Employment Relationship: Emerging International Labour Standards from a Comparative Prospective”. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 19, 43-78.

Vosko, L. F. (2000). Temporary Work: The Gendered Rise of a Precarious Employment Relationship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2006). Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2010). Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vosko, L. F., MacDonald, M., and Campbell, I. (Eds.). (2009). Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. New York: Routledge.

Vosko, L., MacDonald, M., and Campbell, I. (2009). Introduction: Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. In L. Vosko, M. MacDonald and I. Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. New York: Routledge.

Waring, M. (1988). If Women Counted: A New Feminist Economics. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Zeytinoglu, I. U. (2000). “Gender, Race, and Class Dimensions of Nonstandard Work”. Industrial Relations, 55(1), 133-167.

Zeytinoglu, I. U., and Muteshi, J. K. (1999). “Gender, Race and Class Dimensions of Nonstandard Work”. Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 55(1), 133-167.