health and social care

CONCEPTUAL GUIDE TO THE HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE MODULE

Prepared by Katherine Laxer and Pat Armstrong

INTRODUCTION

The health and social care module provides a lens through which to conduct comparative analyses of health and social care workers. It seeks to capture the dynamics of restructuring and precarious employment, using both statistical depictions and library resources. Health and social care is an industry comprised typically of high concentrations of women workers that has undergone fundamental restructuring. This industry is often defined narrowly to include professional and associate professional providers, leaving out a large array of other providers, both paid and unpaid, working in health and social care. The narrow definition is in part reflective of how industry is defined in the statistics; that is on the basis of employer rather than the location of employment. This definitional approach reinforces the invisibility associated with contracting out and the invisibility of groups of mostly women workers in care. It also hides the impact on care providers working within settings where conditions of work increasingly resemble those of other service industries that are accorded little value. Contracting out, supported by such a definition, allows more readily for the replacement of workers by a variety of providers with fewer or no formal credentials and who are paid less or not paid at all. However, the definitions of categories that hide contracting out, combined with different ways of categorizing workers that reflect specific contexts, limit these comparisons in various ways.

Despite variations in the distribution of work across and within countries, and over time, health and social care are primarily women’s work (Doyal 1995; Benoit and Heitlinger 1998; Meyer, Herd and Michel 2000; Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008). Spotlighting the concentration of women in this sector, the World Health Organization observes that “tradition, deeply embedded notions of woman’s social worth and the value of her work, and the distribution of power within a society all explain, in part, why caregiving tasks have fallen disproportionately on women” (WHO 2002: viii). The historical and contemporary association of this work with women is accompanied by the assumption that women are naturally equipped to perform it (Cancian and Oliker 2000; Twigg 2004; Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008). Although women have struggled to make the skills involved visible and valued, much of the work continues to be defined as unskilled, requiring little if any formal training, and thus minimal financial remuneration (Armstrong 2013; Baines 2004; Whitaker 2004). The majority of care work remains hidden in the household, where it is performed primarily by women who seldom have credentials indicating that they have formal training for such work (Armstrong 2012). Yet, the variation across countries and over time, as well as between households and formal economies, demonstrates that there is little that is natural about the division of labour in health and social care. Moreover, research has exposed the skilled nature of the work and the ways women continually teach other women, challenging the notion of women simply doing what comes “naturally” (Nishikawa and Tanaka 2007). Some groups of women who work in care have been relatively successful in their struggle to have their skills recognized and their status acknowledged as professional (Armstrong and Armstrong 2009) or at least semi-professional but the majority still have their work dismissed as simply women doing what comes naturally.

The resources in this module capture some of the variation and consequences of new labour market developments in the health and social care sector. Although it remains necessary to identify the assumptions about women’s innate capacities and skills when developing comparisons, it is also necessary to attend to the structural constraints on their employment, to the relationship between paid and unpaid work and the struggles for both recognition and reward. In addition, it is important to remember that there are significant differences among women in relation to their economic, geographic and other social locations.

Following the lead of Armstrong and Armstrong (2004), the statistical data in this module primarily allow us to do what Deborah Stone describes as “lumping” (2000: 91): emphasizing what is common in women’s work and the kinds of work women share. Though the data lend themselves most easily to lumping, this is not the only reason for doing so. Lumping allows us to establish overall patterns that, for strategic as well as analytical reasons, can be the most effective approach. Nevertheless, much is obscured about both differences and inequities when we focus on patterns for women as a group. We must at the same time be aware of and attentive to differences among women. Miriam Glucksman’s (2000: 16) approach of “slicing” data to create multiple and complex pictures of particular people in particular places, emphasizes difference not commonality. Though slicing is much more difficult to do with the data available, it allows us to establish some differences among countries and to recognize profound inequities such as those related to gender, racialized groups, age, (dis)ability and “spatially related distinctions” (Vosko 2006: 14-15). Statistical analysis of the sort possible here does not permit us to explore several factors such as funding and other health care policies, access to childcare, attitudes towards women and sexual orientation, all of which shape the distribution as well as the nature of the division of labour. Moreover, some work, such as personal care in the home or unpaid extra work in the labour force may not be captured at all (Armstrong and Armstrong 2004).

We think of the limitations in the data as silences and we must continually ask who is missing and what is missing from the statistical portrait we have generated. The noises are created by the availability and construction of the data, shaping what we can see and how we can see it. The module compensates for the statistical silences by turning to the library resource tool and qualitative research including articles and books that point to the factors absent from the data and the sorts of indicators that would better portray this sector.

This module is structured around a set of four key questions. These include:

1. What is health and social care?

2. What are the contexts for health and social care?

3. Who are the care providers?

4. What are the conditions of work?

Our key concepts stem from these questions and include: a) health and social care – medical model, social determinants of health model; b) care context – care region, public, private and not-for-profit, care setting; c) care providers – professionals and professionalization, support providers, unpaid providers, migrant providers; and d) care conditions – schedules of care, care workers’ representation, worker health.

Following a consideration of our key concepts, we describe of our indicators and conclude with a set of demonstrations generated from our comparative statistical tables.

KEY CONCEPTS

Health and Social Care:

Though we define health care and social care as including “all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health” (WHO 2006), silences in the data make it impossible to capture all those involved. These silences are a reflection not only of assumptions about women’s capacities, but also of how care is conceptualized generally. The conceptualization of care matters because it determines how the scope of this industry is demarcated and how categories are defined in the common statistical measures. Approaches to care reflect both ideas about what constitutes necessary, appropriate, effective and efficient care, and ideas about gender, individual and family responsibility, citizenship, and dependency (Fraser and Gordon 1994; Williams 2003). Different approaches to care influence which services are publicly funded and which services are funded privately as well as how services are structured. They shape the practices, locations, built spaces and discourses of care as well as the social relations between care providers and those with care needs. Models of care represent and influence how such ideas are operationalized and embedded at multiple levels of policy and practice. Moreover, models of care underlie both the understanding of care work and the construction of data on this work. There are two dominant models in the health services of high-income countries and both can have similar implications for how health care work is counted.

Medical Model: Much of Western health and social care assumes a bio-medical model of health services. Such an approach defines care primarily in terms of the treatment of body parts based on particular kinds of scientific evidence, with care provided by those with formal training required to employ such evidence (Willis 1983). From this perspective, physicians, dentists and nurses are the primary health care workers. They may be joined by therapists and various technical assistants who support them, many of whom are also identified by formal training requirements. In the bio-medical model, care is separated from other services within the industry and health care is narrowly defined to include only medical treatment or surgery (Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008).

The bio-medical approach distinguishes health care from social care, which is often defined as providing emotional and social support, and which is frequently combined with other means of assistance for daily living such as laundry, food preparation and bathing. Childcare and social work may also be included in the bio-medical model even though this kind of work is much less likely than health care work to require formal credentials and to be recognized as skilled.

Social Determinants of Health Model: For over a quarter century, political economists and other social scientists have been developing a model that focuses on the economic and social determinants of health (Illich 1976; Doyal 1995; Marmot and Wilkinson 2006). There are two ways of seeing this approach. In its most common form, health care is understood as only one determinant among many. This version of the social determinants approach has been used to justify an increasingly narrow understanding that limits the definition of health care to the most acute interventions and the most formally skilled workers, while arguing that health is mainly determined by factors outside the health care system. Thus only those directly involved in providing medical interventions would be included in the analysis of health care work and the rest would be defined out of care. Not surprisingly, the overwhelming majority of the care providers in this second grouping are women. Following this logic, those who provide most of the direct care in homes, communities or long-term care facilities are commonly classified as personal support workers or some similar term implying both that the work is social rather than health care and mainly about what any woman can do. Those who cook, clean, do laundry or clerical work for the ill or disabled are typically defined out of care. Yet this determinants approach can also be the basis for arguing that those factors that influence health outside health care are even more important within health care (Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008). For example, it was learned with H1N1 that cleanliness is the primary defense and research has demonstrated that this is particularly important within health services where immune systems are already compromised. Prior to professionalization and deskilling, much of this work was performed by nurses and recognized as part of care.

With new definitions of care accompanied by the policy and structural changes that support them, more of the work traditionally associated with women becomes less central to what is defined as skilled care work and, hence, becomes more precarious in ways that are reinforced by these models of care. An alternative model, that sees care as relational (Mol 2008; Waerness 1984) in ways that involve a wide array of connections, including all of the factors that determine health, continuity and skills that are often hidden, leads to much different numbers. For the purposes of the module, we try to put as many of the invisible care workers back into the care industry as the data allow, but many are still missing (i.e., silent), and the noises are mainly about those workers defined as professionals. One way we try to include them, which we will describe further in our section on indicators, is to cross-tabulate industry with occupation. By deriving a new variable through this calculation, we can discern those workers typically defined as health care providers within common occupational classifications from those defined within other occupations, such as services or accommodation, but who work within the health and social care industry.

Care context:

The context for care is set at the global, national, regional, and local levels, all shaped by notions of rights and responsibilities for governments and individuals as well as by specific models of care and the role of medicine and women within them (Kittay et al. 2005). Countries vary significantly in the extent to which care is understood as a public good to be delivered as public services, based on universal rights and collective responsibilities. Public involvement has consequences well beyond access as it shapes the nature of preparation for the work, the conditions of work, and the structure of employee rights. It is important then to understand these contexts in using and interpreting the data. The international pressure to make more care a source of profit, combined with pressure to reduce public costs for care and an increasing reliance on migrant labour, has been felt everywhere, but the impact varies with history, conditions, culture and national and local resistance.

Public, Private, Not-for-profit – Blurring boundaries: Virtually no part of any economy throughout the world has been immune to the influence of neo-liberal ideas promoting market approaches (Panitch and Leys 2009; Teeple and McBride 2010). In most high GDP countries, health and social care are increasingly viewed as consumer services suitable for generating profit. International companies have proved to be extremely profitable through the sale of goods and services to those who are ill and disabled, sometimes through the promotion of new diseases that require treatment. New Public Management approaches introduced decades ago promoted the restriction of public services to a narrow range of core functions, leaving the rest for profit-making concerns. For-profit companies have been invited in to deliver services paid for by governments, as well as to offer services no longer publicly provided, such as eye care, medical tests, and childcare in Canada. At the same time, some countries have adopted private sector strategies for the organization of work in the public services that remained. In spite of evidence to the contrary, it was assumed and argued that for-profit strategies could be appropriately applied to the health and social service sector (Armstrong and Armstrong 2010; Hansen 2010).

Competitive bidding as well as the contracting-out of services has increasingly become the norm. “Just-in-time” and/or “just enough” services have become more common, along with new methods for organizing work. Regulations, labour standards and inspections have been relaxed or removed, justified on the grounds that they inhibit the market. Meanwhile, some of the new regulations promote corporate care and limit workers’ rights. Individual responsibility for care has been promoted, with day surgeries, shorter patient stays and the new definition of health care resulting in patients being sent home quicker and sicker. Schools have reduced after-hour care and begun charging for services while public childcare services are constantly under threat. Employment in the female-dominated public care services has become more precarious with the application of market strategies just as more of the responsibility for care has been sent home (Harrington 2000; Bezanson and Luxton 2006; Lyon and Glucksman 2008). More care workers have become self-employed or have been hired for part-time and temporary employment.

Although New Public Management or similar efforts to apply market strategies to health and social care have had a profound impact, it is important to note that there are real limits to this application, limits set by the specific nature of these services. Health and social care are not businesses like the rest for a number of reasons. Most importantly, care is an interactive process, and not just tasks done by one person to another. The necessity of responding to individual demands and variability mean that workers require and seek some measure of autonomy. And finally, care is about life and death, trauma and relationships, creating particular demands from the public as well as from workers. While market strategies have been applied variously, popular support for public care has been prevalent and health care workers can appeal to this popular support in shaping their work. At the same time, governments have sought popular support by claiming that health care costs are out of control and waiting lists too long, hence the need for market methods in order to save the system. And yet labour is sustained by a popular concern for losing public services or for incompetent providers, making this interest group powerful when threatening withdrawal of work compared to car makers, for example. They can also appeal to popular support for practitioners’ control over who gets to practice what, invoking the need for skill and science to protect those requiring care.

Equally important, are the regular irregularities of demands for services (Armstrong and Armstrong 2010) that make it difficult to predict how many workers will be needed at any particular point in time while requiring the maintenance of this essential service. This can mean that managers seek flexibility in their labour force and on-call hours or agency workers, but it can also mean that traditional market means of measuring and controlling labour are difficult to apply. Although the promoted goal of marketization is greater efficiency, better quality and lower costs, these may not be actual outcomes, calling into question the motives underlying these initiatives. For example, a recent study in Denmark on the introduction of compulsory competitive tendering in home care found very little impact on measures of economic performance, suggesting the adoption of such market strategies reflects both hegemonic ideologies and quests for legitimacy on the part of those implementing reform, not to mention the interest of those searching for profit (Hansen 2010).

Care Region: Funding and delivery of health and social care differ not only across but also within countries. In Canada, the provinces and territories, though required to comply with the Canada Health Act, have independent authority over financing and delivery and also the education and regulation of providers. Jurisdictional differences also exist within the United States, where care can differ considerably from state-to-state. Similarly there are differences within the United Kingdom. Care can also differ on the basis of rural or urban milieu. Finally, with the growth of medical tourism, care regions for patients are gradually extending beyond the borders of their resident country, opening whole new fields of profit-making for low-income countries with ramifications on employment in high income countries. India and Mexico, for example, have become popular destinations for high-end surgeries and other care that is either not provided by resident countries, is cheaper in the destination country, or is more readily available for patients offering to pay the right price. At the same time, some countries such as the Philippines, have invested in health care providers intended for employment in other countries.

Care Setting (institutions, private homes): Health reforms in all high-income countries have supported the relocation of workers to workplaces that have traditionally been lower paid and more precarious (WHO 2006). As hospitals focus on more acute care, day surgeries and shorter patient stays, more of the care work is done elsewhere (Glazer 1990). Some work is done in long-term care facilities and some in group homes or other forms of assisted living was well as in retirement homes and in private households (Leys 2003; Harrington et al. 2004; Lilly 2008; Armstrong et al. 2009). In North America, employment in these areas is much less likely to be unionized. It is much more likely to be delivered by a for-profit agency and by workers defined as unskilled.

The relocation of care from hospitals to other institutional settings has occurred alongside the relocation of care to unpaid care in the home. Governments and employers have been shifting care work into the home, often arguing that it has traditionally been done there. However, the kinds of complex care that are increasingly shifted to the household were never done there before and home settings can be unsanitary, unsafe, and unequipped with the devices needed for intensive care. This allocation of health and social care to households contributes to the precariousness of women’s employment in the formal economy (Lilly et al. 2007). It makes it harder to defend the skill involved in paid work at the same time as it allows governments to limit women’s employment in the sector (Armstrong and Armstrong, 2010). With growing household demands putting pressure on women’s labour force work, women’s health as well paid work can become more precarious (Duxbury et al. 2009).

Especially affected by precarious employment are the many women who work as paid domestic workers in the home, providing direct care and other forms of labour related to care (Blackett 1998; Hochschild 2004; Ehrenrich and Gallotti 2009; Chang 2006). The demand for domestic workers has increased with cutbacks on public services and women’s high rates of employment (Zimmerman et al. 2006). Many workers engaged in domestic employment are dependent for their residency status in the country of their employer, adding a dimension of insecurity (Sweetman and Warman 2010). This discussion is further explored in the module on migration in the gender and work database, and in the module on temporal and spatial dynamics in the CPD.

Care Providers:

In recent years, there have been concerted attacks on the barriers between professions and efforts to make the boundaries around scope of practice more permeable (CIHI 2007). Managers favour such a development because it allows more substitution for a more expensive worker by a cheaper one and reduces control by the profession. Some professions support this process as well, seeking to expand and employ their full range of skills. Nurses, for example, have been seeking the right to do some aspects of work previously restricted to physicians (Allen 1997; Coburn et al. 1999) while personal support workers are seeking to do some work previously restricted to nurses. The result may be both multi-skilling and multitasking, both of which can contribute to greater precariousness (Blackett and Shepard 2003). The process can also mean a devaluing of skills, as opposed to upgrading them.

Professionals and Professionalization: The particular nature of health and social care, as well as the previous domination by university educated men, helps explain why physicians have been successful in demanding relative autonomy over not only their own practices but also over which workers can practice and what they must know to do so. Just as women have moved in large numbers into medicine (e.g. Riska 2001; Riska 2008), however, physicians’ power has come under threat from governments and insurance companies as well as from nurses, through both direct and indirect efforts to exert control over them or limit their scope of practice. In some countries, these efforts to control mean physicians’ work has become more precarious. However, self-employment and flexible working hours do not necessarily equate with precarious employment, given that physicians often have relatively high income and autonomy.

Nurses in many countries have followed the example of physicians and organized as professionals in an attempt to have their skills recognized and to protect their work through state support for their right to practice (Clark and Clark 2003; Armstrong and Silas 2009). They have also sought to shed some of what they defined as non-nursing tasks, partly in an effort to establish their work as skilled and distance themselves from women’s work. Although they have been hampered by their gender, they have enjoyed some success in achieving skill recognition. However, nurses have not gained the kind of autonomy or influence enjoyed by physicians, in part because of the power gained earlier by the mainly male physicians (Witz 1992). In some ways, nurses’ efforts fit well with management interests, because nurses allowed tasks to be separated out, defined as less skilled and, in consequence, made more precarious. In addition, some nurses have escaped oppressive conditions of work and managed to deal with the increasing demands for extra unpaid work by seeking employment through temporary help agencies. This strategy of mitigating oppressive conditions too fits with efforts toward a more flexible labour force, paid only when the work is in high demand.

The nurses’ move towards professionalization has been followed by other workers in the health care field, with varying degrees of success depending on the policies and regulations at the national and local level as well as on gender politics at all levels (Lindsay 2005; Armstrong and Armstrong 2009). Their organizational strategies have the paradoxical outcome of resisting some forms of marketization while reinforcing others.

The struggle for the professionalization of medicine and nursing has served to both limit access to employment in these fields and ensure that people with specific measured skills do the work (Coburn et al. 1999). The kinds of formal training that are mandated vary in ways that reflect the history of struggle as much as the established evidence on what is required, creating challenges for comparisons across national boundaries or even within them. For example, many high income countries increasingly require university degrees for registered nurses, while some jurisdictions still rely on college diplomas or hospital training. Some require four years, some three and some two years of formal education. The evaluation of foreign credentials is particularly difficult, especially when ideas about race and culture are part of the mix. Though all countries have established methods for accepting foreign credentials, these methods vary in terms of content and process. They shape the silences and noises in the data.

While all countries have clear rules about who can practice medicine and nursing and about what kind of education is required, the farther we move away from these clearly defined occupations, the more vague and varied the rules become. Increasingly, technicians, therapists and some assistants have formal education and credential or licensing requirements and have their own professional organizations, some of which allow them to self-regulate. The emergence of professional organizations, education, and credential requirements tend to create clear boundaries between occupational categories and provide some protection from competition for workers. Countries vary in the extent to which it is difficult to move from one profession to another, but in all countries such a move requires more formal education although the nature and permeability of the boundaries among them vary greatly.

It should be noted that professions often self-regulate, determining what is required to practice and who can practice. Professions often also act like unions, negotiating wages, conditions and benefits.

Personal Care and Support Providers: As a result of both managerial strategies and workers’ efforts, the division of labour in health and social care has become increasingly complex, especially in North America. Along with national regulations and legislation related to health and social care work, these efforts have led to some differences among countries in the division of labour. While all countries in this project have occupational categories for nurses and physicians, what education and credentials they are required to have, their scope of practice and their conditions of work vary significantly. Differences are even greater as soon as we move away from these two categories to include those who take up the tasks shed by these providers and who are, under our approach, counted as part of the health care workforce (for a description of how we calculate this group, please see the section on indicators for this module described below). In countries such as Canada, these workers make up the majority of the health care workforce (Armstrong, Armstrong and Scott-Dixon 2008). They are the clerical, cleaning, laundry, cooking, personal support and homemaking jobs that are primarily done by women and often by women from racialized and/or immigrant communities (Lyon and Glucksman 2008). Many are hired as part of the informal economy, making them even more difficult to trace.

Research has shown support workers to be a particularly precarious group of care workers (Armstrong and Laxer 2006). In Canada, those with collective representation tend to belong to unions based on numerous occupational categories. The boundaries among these occupations are often blurred and allow occupational change, in part because there are few formal educational or credential requirements. This lack of formal requirements may allow easy substitution of one worker for another, limiting workers control and reinforcing precarious employment trends. It contributes to the growing concentration of immigrants and migrant workers among support workers given the absence of restrictions based on credentials. The absence of clear boundaries, combined with very different approaches to education, the division of labour and scope of practice among these workers, make it particularly difficult to develop comparisons across national boundaries or even within them. Measurements of industry and occupation further obscure conditions faced by support providers given that some may not be accounted for in health care workforce statistics. Moreover, some may be informally employed and entirely invisible in the data. This seems to be the case, for example, of those so-called personal companions who are paid by families to help care for their relatives in long-term care facilities.

Unpaid Providers: The bulk of the work in health and social care is done at home without pay, primarily by women (Armstrong 2012; Duxbury et al. 2009; Keefe 2010). It is difficult to capture this work with any accuracy, in part because it is unpaid, in part because it is hidden in the household, and in part because it is combined with other forms of domestic work. In Canada, it will be even harder to capture in the future because the question on unpaid work has been removed from the Census. Also challenging to capture is unpaid extra work performed by paid workers. Referred to as compulsory volunteerism by Baines (2004: 268), this is work that is expected by employers, places additional burdens on care providers, and contributes to the “deskilled and exploited nature of caring labour.” Unpaid care by family members and friends in institutional settings is increasingly recognized by researchers but equally difficult to account for with existing statistical resources. Finally, there are the volunteers who provide care both in homes and institutional settings. Some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Italy, are more reliant on this unpaid care than others (Lyon and Glucksmann 2008). In the Netherlands for example, health policy emphasizes family responsibility for long-term care and has encouraged the growth of respite services provided by unpaid volunteers (Lyon and Glucksmann 2008). Volunteer care, sometimes backed by professional paid care, can reinforce the precariousness experienced by paid providers by contributing to assumptions that the care requires less skill and training, and hence, merits less remuneration. Unpaid work of all varieties affects families and labour force participation, along with the structure of communities (Armstrong 2012; Hodgetts, Pullman and Goto 2003; Lilly, Laporte and Coyte 2010).

While the countries included in the CPD have attempted to capture some of the unpaid care work, the ways data are collected often fail to count the bulk of the daily work involved and the variety of unpaid contributions. Unpaid work is not included among the indicators of health and social care because of the lack of available data from CPD surveys.

Migrant Providers and Migration: Several countries supply a source of migrant labour for health and social care services in wealthier countries (Misra, Woodring and Merz 2006; Spencer et al. 2010). Nurses and childcare workers have, for example, become a major “export” for the Philippines (Ball 2004; Salazar Parrenas 2006). Their migration has a gendered impact on employment and divisions of labour in both high and low income countries. It reflects and reinforces the view that aspects of care require few skills and that workers are easily replaceable, require little to no training, and deserve low pay and few benefits (Salazar Parrenas 2006; Bourgeault and Wrede 2008; Hassim 2008; Sousa Ribeiro 2008). With health care workers motivated to move by higher wages in other countries, the outflow leaves gaps in the availability of qualified care providers in source countries (Vujicic et al. 2004). Given the often informal nature of this care, statistical measures are poor, but trends are nonetheless observed in countries like Italy and the United Kingdom where there is a notable reliance on migrant providers (Sciortino 2004; Lyon and Glucksmann 2008). Certain areas, such as countries of the Mediterranean, cluster in this trend towards attracting migrant providers, “ushering in a new division of labour among family carers (mainly women), female immigrants, and skilled native workers” (Bettio, Simonazzi, and Villa 2006: 271). Migration of professional groups differs in many ways from the migration of support and domestic workers but is also influenced by state policy and sponsorship programs, reflecting the interests of both receiving and source countries and guided in part by international organizations encouraging the development of global standards (Allsop et al. 2009). Migrating workers in health and social care encounter challenges around the recognition of professional and/or educational credentials and licensure that impact their ability to find appropriate work in their area of skill. This can have bearing on psychological well-being and professional identity (Austin 2007). Measuring this workforce, its characteristics, and the overall patterns of largely female migration generated by health and social care reform, is very challenging. It is taken up in part in the CPD module on temporal and spatial dynamics.

Care Conditions:

Schedules of Care: The provision of much health and social care is around the clock; it involves providers seven days a week, twenty four hours a day. It is not only nurses and physicians who do shift work; it is also cleaners and personal support workers. Indeed, more personal support workers and cleaners than physicians work in shifts. Because shifts are an integral aspect of the work, shift work alone cannot be taken as an indicator of precarious employment even though shift work of any kind has health consequences. Gender can affect the impact of shifts on health given that women spend more time on childcare and household responsibilities than men and hence encounter greater stress from balancing responsibilities (Wong, McLeod, and Demers 2010; Wong et al. 2011). It is important to know whether workers have some control over which shifts they work and whether shifts are planned and confirmed well in advance to allow workers to organize other aspects of their lives. Split shifts have become common in some workplaces, designed around peaks in demand such as mealtime or morning baths and reflecting the strategies taken from the market rather than simply the demands of the work (di Martino 2003; Baines 2004a). Irregular hours are also common in health care, although harder to justify as necessary for the work itself. Given the irregular nature of care demands, the push to reduce care hours to the lowest possible numbers means that managers are increasingly relying on calling in workers for short shifts on short notice. Overtime, both paid and unpaid, has also grown as care providers seek to and are required to make up for the care deficit caused by new managerial strategies (Baines 2004b).

Care Workers’ Representation: Unionized workplaces and those with strong professional associations are likely to have more formal seniority rights and job security, and are less likely to be associated aspects of precarious employment (Jackson 2005; Anderson, Beaton and Laxer 2006). Contracting out of health and social care work makes jobs less secure, as does the adoption of market strategies for jobs that remain in the public sector. Both have resulted in more part-time and casual employment in the health and social care sector. The shift from public to private employer frequently means a loss of union protection as well as of benefits, given that unionization is more common in the public sector, especially for women (Stinson 2004). It also often means a move to a smaller employer or self-employment, both of which frequently mean a loss of benefits and union status (Armstrong and Armstrong 2009; Cranford 2005; Vosko 2006). With relaxed labour standards, especially in areas no longer defined as health services, such workers too often find themselves with little protection. In countries like the United States that rely more on private health insurance, the move to the for-profit-sector, and especially to small firms or to self-employment, can mean a loss of access to health and social care services (Clark and Clark 2003).

Worker Health: Illness and injury rates have been steadily rising among different groups of care providers, making health and social care one of the most dangerous places to work. This is the case even though women are less likely than men to have their illness or injury attributed to their paid work and are less likely than men to report such work-caused health problem (Messing 1998). Care providers have long been at risk from exposure to disease and patients who may become violent (di Martino 2003; Baines 2006). The lifting involved in childcare, patient care, laundry and cleaning work constitutes a health hazard (Vogel 2003; Waters 2006). Needle sticks and other injuries from equipment have also long been a problem. Shift work, particularly night and rotating shift work, is essential to the nature of work in the sector, but has been linked to injuries and to alarmingly disproportionate rates of cancer (Wong, McLeod, and Demers 2010). The speed up of the work under new management strategies, the limited autonomy, and the lack of continuity resulting from part-time and temporary work, have each contributed to increases in illness and injury rates among care providers (see, for example, Lipscomb et al. 2004). Those who work in homes are particularly vulnerable because they work alone, although low staffing levels can also mean care providers in facilities are frequently working alone. Gender influences the risks and outcomes related to occupational health and affects both paid and unpaid providers (Briar 2009). Workers in health and social care are frequently the target of abuse and violence and some work settings report alarming rates of harassment due to factors such as isolation, poor training, and gender (Banerjee et al. 2012; International Labour Organization 2003; Findorff et al. 2004; Morgan, Stewart et al. 2005; Banerjee et al. 2008)

INDICATORS

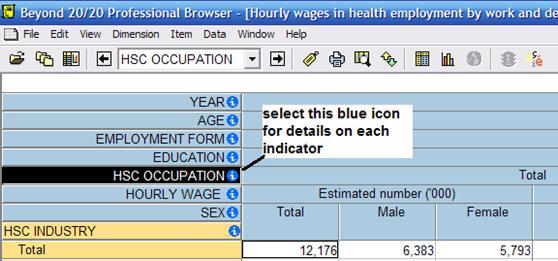

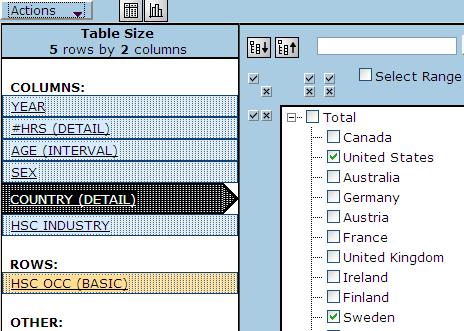

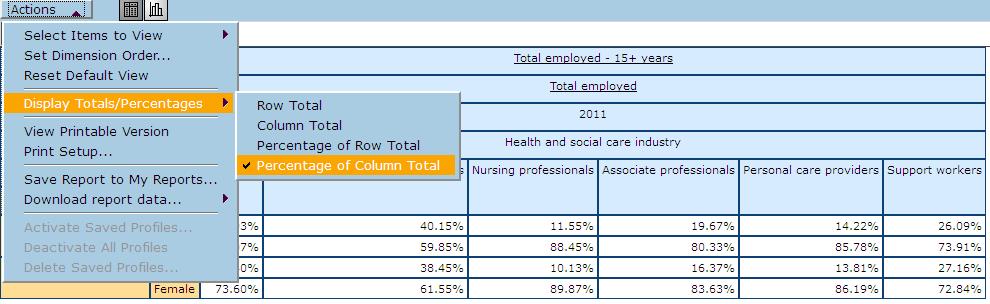

The indicators for health and social care are designed to reflect our conceptual framework, with indicators aimed for each key area: health and social care, contexts of health and social care, health and social care providers, and, conditions of health and social care work. Users are urged to examine indicators selected for use by referring to the harmonized codebook + data dictionary. For example, some indicators, though measuring the same concept, are not directly comparable for every country. Our Beyond 20/20 tables include information links for each indicator and users can also refer to these for details on harmonization (Image 1).

Image 1: Example of Indicator Information Links in a CPD Beyond 20/20 Table

Indicators – Health and Social Care:

We use two indicators to measure the health and social care industry. The basic measure, Health and Social Care Industry, is included within the collapsed industry codes of WC1G1. This measure allows users to compare the health and social care industry with twelve other industries. Our second measure of the health and social care industry (HS1G1) classifies the workforce into “Health and Social Care Industry” and “All Other Industries”. This indicator allows users to focus in on the health and social care industry either to examine it independently or in comparison to all other industries combined:

HS1G1: Health and Social Care Industry

1. Health and Social Care Industry

2. All Other Industries

With the exception of the Current Population Survey from the United States, the survey data samples used by the CPD do not break down the health and social care industry into sub-industries so we were unable to provide a more detailed harmonized health and social care industry variable. However, the health care module of the gender and work database, though using only Canadian survey data, provides detail on the health and social care sub-industries and includes data for the hospital, ambulatory, nursing and residential care, and social assistance industries. Research examining sub-industries in health and social care indicates that subcategory makes a difference in a variety of areas, although lumping the data in this way does reveal some overall patterns and may make international comparisons more accurate, given the variations in definitions as well as in practices at the more specific levels.

Indicators – Care Context:

Our indicators of care context include indicators of time, place, and sector. Time, measured by year, allows users to investigate changes – such as policy and restructuring shifts – affecting the health and social care industry. Data are available for select years from 1983 on. For place we use country and supranational grouping as our indicators. These allow users to examine policy and regulatory contexts associated with particular jurisdictions that align with these geographic distinctions. Some jurisdictional differences are relevant as well at sub-national levels (such as at the level of provinces in Canada), however, due to sample size and other restrictions, the CPD was not able to provide this level of detail. The simplest breakdown of country/supranational grouping available is GE2G1, which includes Australia, Canada, the United States, and the EU27. The most detailed variable for country is GE1G1, which classified samples for Australia, Canada, the United States, and each individual European Union country. Here, too, greater detail reveals regional differences hidden by national level data.

We were limited for our indicator of sector. Though our aim was to provide data on the public, private, for-profit and not-for-profit sectors, the survey samples used by the CPD do not include variables with all of these distinctions. In general, few national surveys collect data on for-profit and not-for-profit labour forces. Consequently, our indicator includes public and private only and is available for Canada, the United States, Australia, and in earlier data, for European countries (WC3G1). When the EU SILC replaced the EU ECHP, it no longer measured sector. The US CPS has collected data on the for-profit and not-for-profit workforces but the sample from this survey that was suitable for harmonizing does not include this variable. The literature indicates the employment conditions vary significantly among these categories.

Indicators – Care Providers:

We have derived two health and social care occupation indicators (HS2G1 and HS2G2) to offer users detail on specific health occupations and we also use a set of social location indicators such as sex, age and immigrant status to measure demographic information. While other social locations are often equally important, these are the only ones for which data are available. Our first measure of health and social care occupations (HS2G1) codes occupations groups into either the health and social care industry or into all other industries combined. This allows users to capture all workers who work in health and social care but who may not be classified in “health occupations” by occupational classifications, such as support workers.

HS2G1: Health and Social Care Occupations

1. Managers

2. Professionals

3. Associate professionals (including personal support in Canada)

4. Personal care providers

5. Support workers

This measure allows for the distinction among managers, professional providers, associate professional providers, personal care providers which includes childcare, homecare and personal support, and support workers which includes occupations such as cleaning, food services and laundry. Users should note that some support providers working in health and social care settings may not be classified within the health and social care industry if their direct employer is a contractor and is classified in another industry (such as accommodation and food service, or other services). Though we would conceptually define these workers as part of health and social care, the manner in which they are classified prevents us from including them. With the growth of contracting-out, this classification issue is an obstacle to understanding and profiling differences among in-house and outsourced health and social care workforces.

Not all national survey samples used by the CPD allow for straightforward harmonization of health and social care occupations. For example, the Canadian data used by the CPD collapses “personal support” workers with “associate professionals”, meaning users should be cautious with categories #3 and #4 in HS2G1 when Canada is included in a comparative analysis. The harmonization of Australian data is also unique as the occupation variable from the HILDA used by the CPD collapses “personal care providers” in such a way that this category could not be pulled out for HS2G1 and HS2G2.

Our final measure for health and social care occupations is HS2G2 and provides the most detailed breakdown of occupational categories by separating physicians and other professionals from nursing professionals:

HS2G2: Health and Social Care Detailed Occupations

1. Managers

2. Physicians and other professionals

3. Nurses

4. Associate professionals

5. Personal care providers

6. Support workers

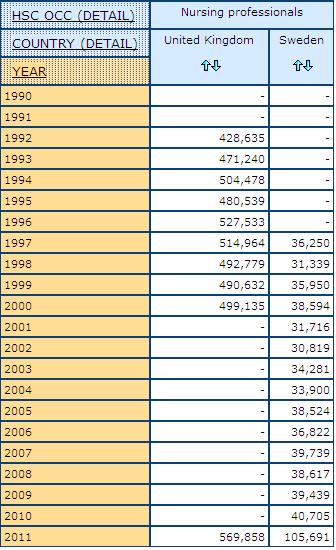

Not all countries allow for the separation of nursing professionals from physicians and other professionals. As a result we could only harmonize this variable using the European Union Labour Force Survey, the Canadian Labour Force Survey and the United States Current Population Survey. The countries within the EULFS have some differences in the amount of occupation detail available and the detail may vary by year depending on the country. For example, between 2001 and 2010, occupation data for the United Kingdom does not separate out nursing professionals (Image 2), a result of data submitted from the UK to Eurostat during those years.

Image 2: Example of Country and Year Variability in the Availability of Data on Nursing Professionals

Age and sex are among our social location indicators for care providers (DE2G1, DE2G2, DE2G3 and DE1G1). Each health and social care table uses one grouping of age and the variable for sex. Some tables provide measures of citizenship and immigration status, both important indicators of social location among health and social care workforces in different countries and regions (DE4G1, DE4G2). Educational attainment and student status are included in some health and social care tables. Differences in educational systems make it challenging to compare the relationship between education and health and social care cross-nationally. However, our indicators on education offer some good comparable distinctions such as “low” to “high” educational achievement (DE5G1) and “less than high school” or “high school or more completed” (DE5G2),), along with two student status indicators (DE6G1 and DE6G2).

Indicators – Care Conditions:

There are several indicators we use to map working conditions in health and social care. These include indicators of forms of employment, regulatory protection, wages and income and most are explained in greater detail in the forms of precarious employment module. For forms of employment, we include variables for full-time/part-time (FE3G1, FE3G2, FE3G3) and for temporary/permanent (FE4G1). Firm size and establishment size are used in health and social care tables as indicators of precariousness since these, in some contexts, are related to access to benefits and stability of employment, with large employers more likely to provide benefits (WC5G1, WC4G1). For measuring aspects of control over the labour process and worker representation we include an indicator of union status (WC6G1) in some tables. We also use several indicators of income, wages and benefits.

Indicators for care conditions that build upon concepts centrally explored in the module on health and social care, such as schedules of care and occupational health, are included in several tables. To measure schedules of care, the CPD has harmonized variables for work schedule:

WC8G1: Work Schedule

1. A regular daytime schedule

2. A regular evening shift

3. A regular night or graveyard shift

4. Other shift work

To look at occupational health, we harmonized variables measuring worker absenteeism and disability and illness. The CPD indicator for absenteeism (HS3G1) classifies absenteeism according to several reasons including “illness, injury and/or temporary disability”, “personal, family”, “vacation”, “labour disputes”, and “other”. We had challenges harmonizing absenteeism data and we urge users to read the details for this indicator (HS3G1) in the harmonized codebook + data dictionary. For example, the Canadian Labour Force Survey variable looks at reasons absent for a full week, while the European Union Labour Force Survey and the United States Current Population Survey look at those absent during the reference week. Our aim was to provide an indicator on “number of days absent” over a particular reference period, however, the survey samples used in the CPD do not include variables that can allow for this type of absenteeism indicator.

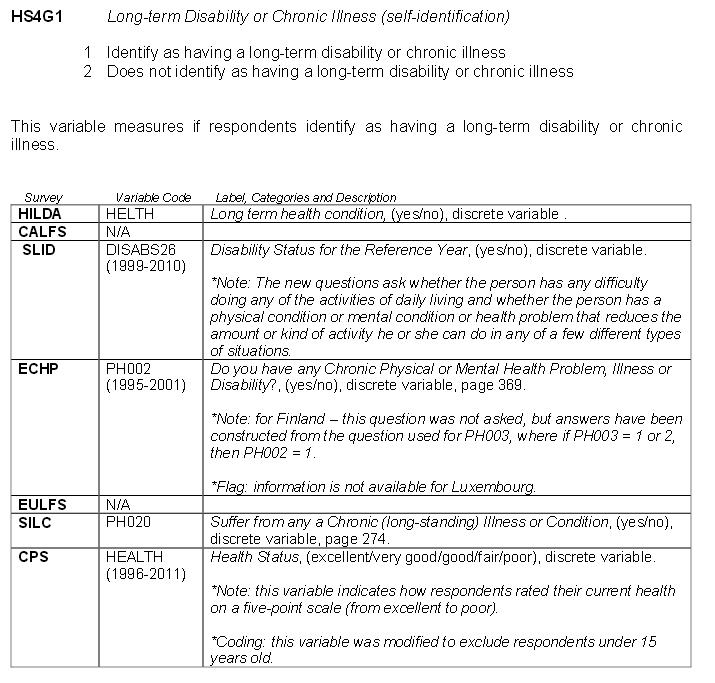

For disability and illness, we have included two indicators (HS4G1, HS4G2). One measures whether or not a respondent identifies as having a long-term disability or chronic illness, the other measures those who have a long-term disability or chronic illness that affects their work. The reason “illness and injury” is also included in the variables for “reason for working part-time” (WC11G1) and “reason for leaving last job” (WC10G1). The health and social care module includes these reasons variables in tables exploring occupational health. Users are urged to consult the harmonized codebook +dictionary for details on indicator harmonization (example Image 3).

Image 3: Example of harmonized codebook + data dictionary Information for Indicator HS4G1

STATISTICS DATABASE

The cross-national comparative statistical tables of the CPD, using the indicators described above, enable researchers to focus on aspects of precarious employment in relation to health and social care. The statistics database can be used to obtain basic information on a topic (e.g., cross-national comparisons of women’s labour force participation) or to examine complex social relations (e.g., gendered precariousness in different countries). The statistical tables are displayed in Beyond 20/20, enabling users to manipulate the data. University and community users doing non commercial research and teaching may access the statistical data. For more information on the data harmonization approach of the CPD, please consult the introduction. Below we have provided links to the statistics database and to information on how to apply for access. Following these links we provide three demonstrations of the data available within the health and social care module, with our key questions guiding our approach.

statistics database

DEMONSTRATION 1

A guide to the health and social care statistical tables

The following demonstrations of the health and social care module begin with several image shots from our Beyond 20/20 multidimensional tables to show users some of the navigation features within the statistical database. We then provide two analytical demonstrations showcasing CPD health and social care data.

Beyond 20/20 Health and Social Care Tables

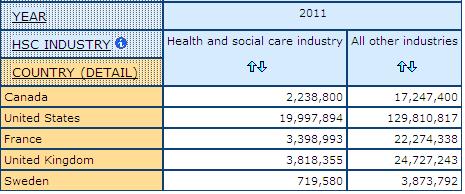

Most health and social care module tables allow users to compare counts of workers in the “health and social care industry” with those in “all other industries”. This variable is cross-tabulated with several CPD indicators to build multidimensional tables on work context, care providers and working conditions. Image 4, from a health and social care Beyond 20/20 table, shows counts for the health and social care industry and for all other industries cross-tabulated with a selection of CPD countries.

Image 4: Example of a Health and Social Care Beyond 20/20 Table

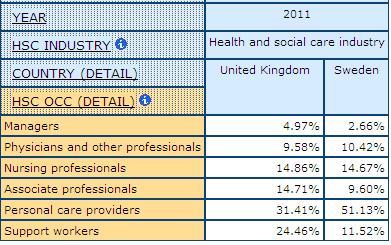

Occupation is included in most tables. The images below demonstrate the two variables that harmonize health and social care occupation data using a comparison of the United States and Sweden as an example. Image 5 shows how to select these countries out of the list of countries.

Image 5: Example of Variable Selection within Beyond 20/20

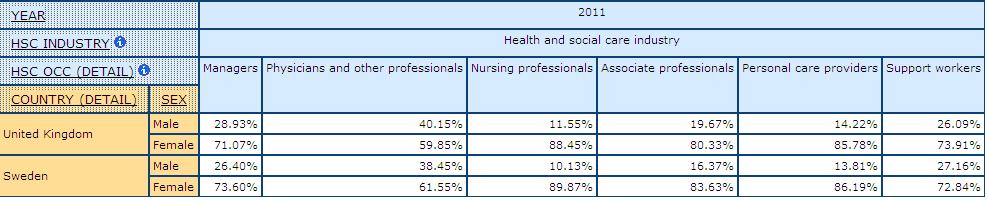

The next images show the United States and Sweden where column percentages have been calculated, demonstrating some of the different configurations and calculations users can make within the CPD Health and Social Care tables.

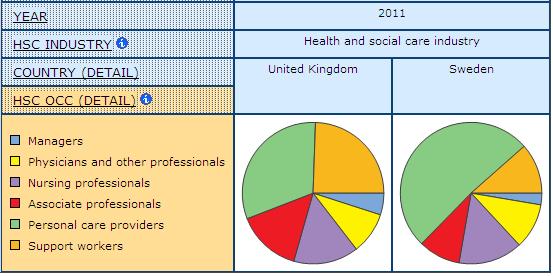

Image 6: Table Output for the United States and Sweden with Column Percentages Calculated

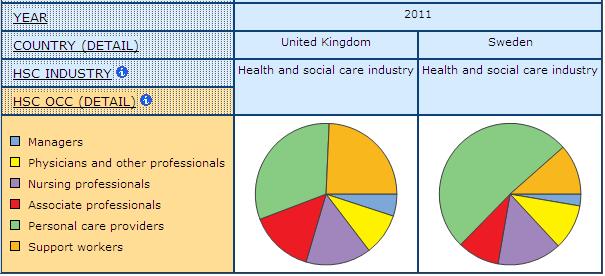

Finally, Image 7 demonstrates a pie visualization that can be done in Beyond 20/20, allowing users to quickly spot differences in any comparisons. In this case the pie visualizations are comparing the division of labour in health and social care in the United States and in Sweden using the basic indicator for health and social care occupations (HS2G1) which has five categories including “managers”, “professionals”, “associate professionals”, “personal care providers” (includes personal support workers, care aides and childcare workers) and “support providers” (includes ancillary occupations such as cleaning, food services, maintenance and other workers).

Image 7: Example of Data Visualization within Beyond 20/20

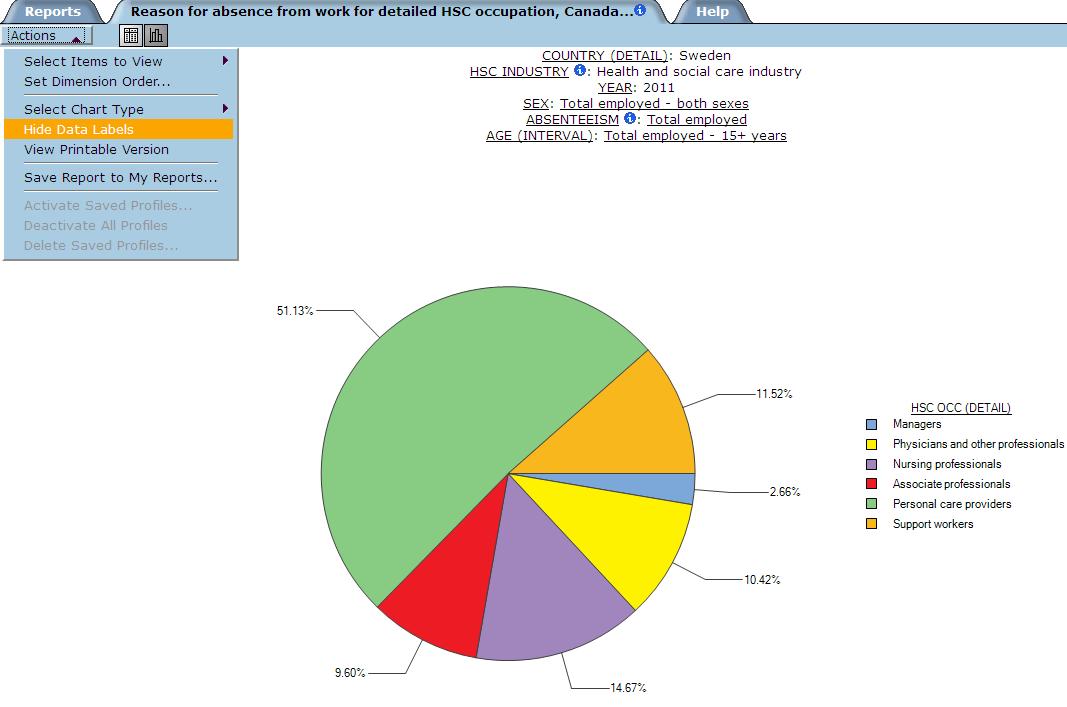

Visualizations may or may not include data labels when several are compared in one table. However, users can select to consider in more detail any visualization or chart by clicking on the image. Image 8 shows an example of the pie above for Sweden which has been selected and for which the data labels have been added (or can be hidden) using the “actions” function within Beyond 20/20.

Image 8: Displaying Data Labels within a Beyond 20/20 Visualization

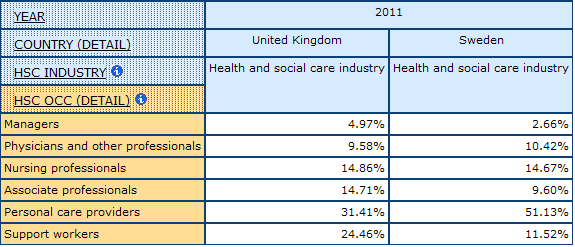

Image 9 features some additional navigation options within the program. Indicators can be moved around and/or collapsed to produce a table with particular variable layouts. Finally, Image 10 shows the output using the more detailed occupation variable that breaks down the category of “professionals” into “physicians and other professionals” and “nurses” (HS2G2). Though not available for all surveys and all years, where possible we use this detailed occupation variable in the tables of the health and social care module. In this case, we have selected to compare the 2011 percentage concentrations of men and women within the detailed occupational categories for Canada, Germany and for all countries represented by the CPD (“total”).

Image 9: Example of Table Calculation Options within Beyond 20/20

Image 10: Output from Column Percentage Calculations Shown in Image 9

DEMONSTRATION 2

The division of labour in health and social care

This is the first of two analytical demonstrations of the health and social care module. We have selected the United Kingdom and Sweden for comparison and we begin with an analysis of the gendered and racialized division of labour in health and social care in these two countries. Throughout our demonstrations we showcase many of the module indicators described above along with many different configurations of health and social care module multidimensional tables.

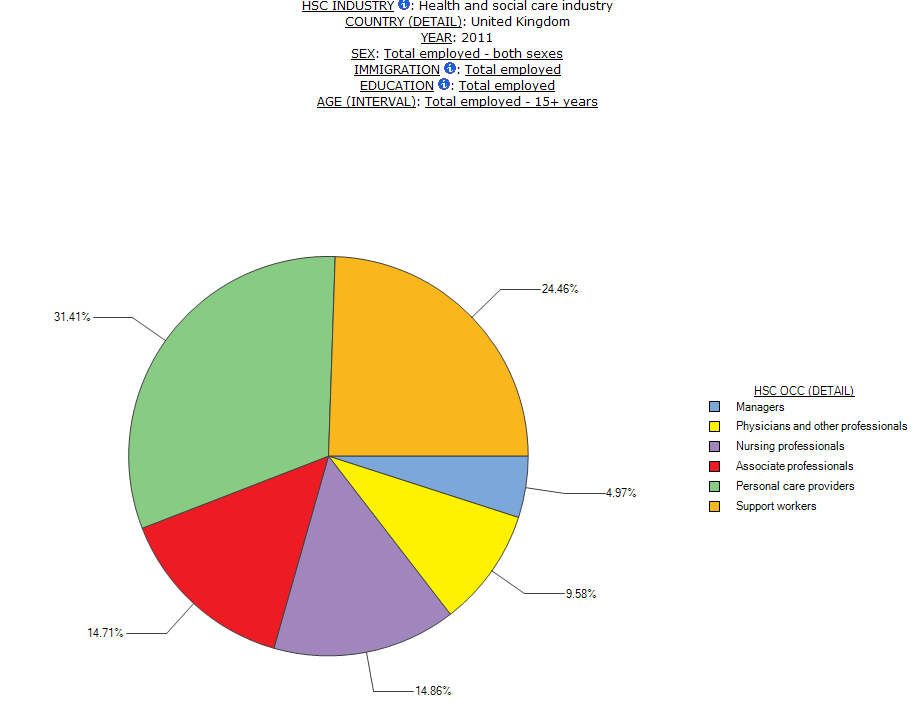

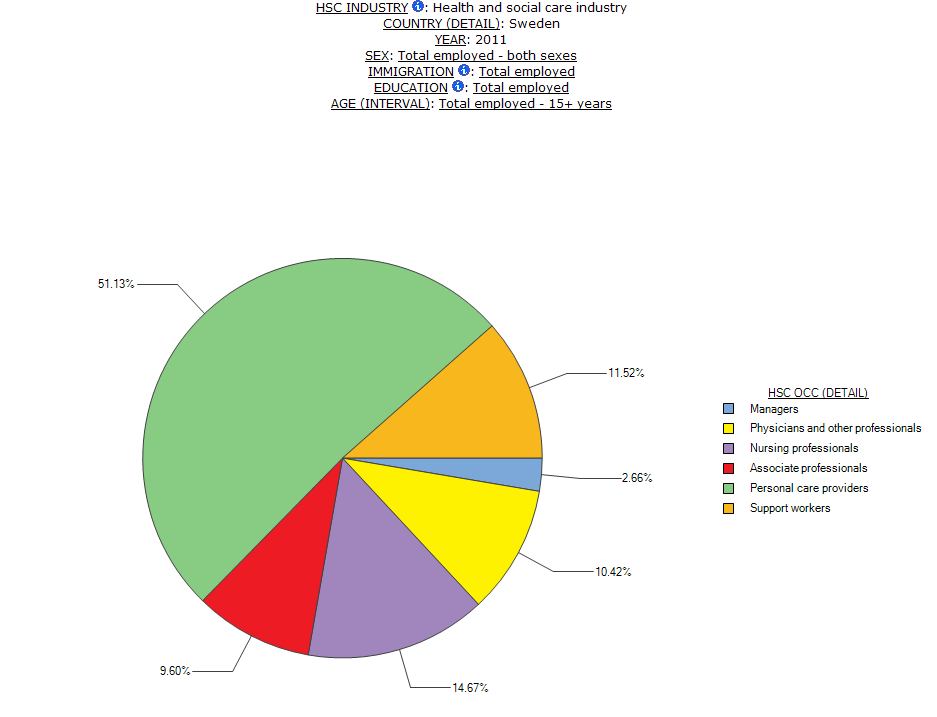

The occupational division of labour varies across the countries of the CPD and a comparison of Sweden and the UK offers a good example of some of the differences in how work gets divided up within health and social care in different contexts. The most significant difference in the division of labour is in the number of workers who work as personal care providers as compared to the number who work as support providers. In Sweden, there is a much larger concentration of workers in personal care provider roles than in the UK (Table 1). Specifically, 51.1% of workers in health and social care in Sweden work as personal care providers, as compared to 31.4% in the UK. Conversely, 24.4% of workers in the UK work as support providers (i.e. cleaners, food service workers, clerical, among others) while only 11.5% of Swedish health and social care workers are in support provider occupations.

Table 1: Occupational Division of Labour in HSC in the UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

This difference suggests that cleaning and laundry work is done by workers who are classified in another category in Sweden because they do other work as well. Indeed, comparative research on long-term residential care shows that the division of labour differs between Sweden and Canada and that personal support workers in Swedish facilities also do cleaning and other work (Daly and Szebehely 2012). The division of labour and the organization of work have important implications for workers. Daly and Szebehely’s research shows that the Canadian model of “highly differentiated task-oriented work” in long-term residential care contributes to more demanding working conditions as compared to the Swedish model of “integrated relational care work” (2012). These data show that the division of labour in the UK is much like that found in Canadian long-term residential care, where tasks are divided up among different occupational groups. Chart 1, Chart 2 and Chart 3 demonstrate the data on occupational division of labour shown in Table 1 as pie visualizations that depict this significant difference in the size of the personal care provider workforces in these two countries (represented by green).

Chart 1: Visualization of the Occupational Division of Labour in HSC in the UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Chart 2: Visualization of the Occupational Division of Labour in HSC in the UK with Data Labels, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Chart 3: Visualization of the Occupational Division of Labour in HSC in Sweden with Data Labels, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

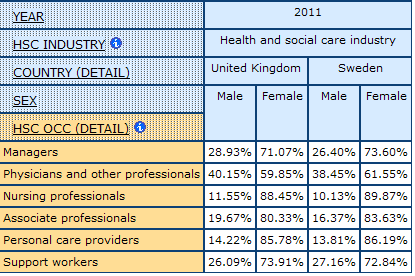

The division of labour is gendered in both countries. Men and women are concentrated in different types of work and these concentrations vary by country. Table 2 shows shares of men and women within health and social care occupations for the UK and Sweden in 2011. Women outnumber men in all occupations except for “physicians and other professionals”, where men outnumber women in the UK but not in Sweden. There are larger shares of men working in support provider occupations in both countries.

Table 2: Shares of Men and Women by HSC Occupation, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

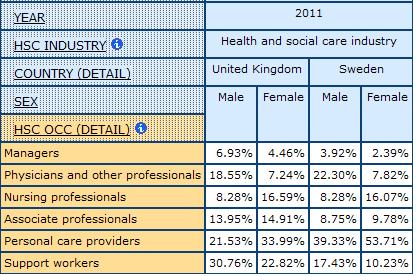

The division of labour differs for men and women in health and social care. By exploring the division of labour within each sex we uncover patterns that demonstrate both where men and women work in care and how care work is divided up within particular countries. Table 3 shows the occupational division of labour among men and among women working in health and social care in the UK and Sweden in 2011. Out of all men working in health and social care in the UK, 30.7% work as support providers, while in Sweden only 17.4% of men in health and social care are in these jobs. More men are concentrated in personal care provider jobs in Sweden, again pointing to the difference in how care work is configured in these two countries, with personal care providers in Sweden likely performing the tasks that support providers do in the UK. There are similar concentrations of men and women working as physicians and other professionals in both countries. In sum, men and women are segregated into different types of care work with larger concentrations of women in jobs that are typically less well paid, have risky working conditions and are often depicted as unskilled.

Table 3: Occupational Division of Labour Among Men and Women, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

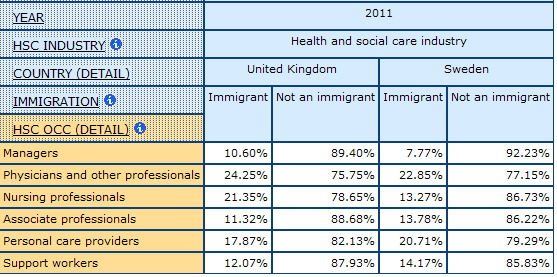

The division of labour is also racialized in health and social care and some occupations in some countries show larger than average concentrations of immigrant workers. Table 4 shows shares of immigrants, a CPD proxy for racialized workforces, in each of the occupations in health and social care for both countries. In the UK, there are higher than average concentrations of immigrants among physicians and other professionals, while in Sweden disproportionate shares of immigrants are found among personal care providers.

Table 4: Shares of Immigrants and Non-immigrants by HSC Occupation, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

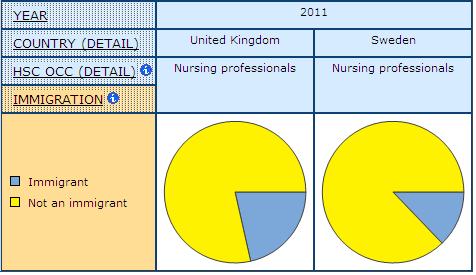

Notable are the different concentrations of immigrants among nursing professionals in the UK and Sweden. In the UK, 21.4% of nursing professionals are immigrants as compared to 13.3% in Sweden. Chart 4 provides a visual depiction of this difference.

Chart 4: Visualization of Shares of Immigrants and Non-immigrants among Nursing Professionals, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

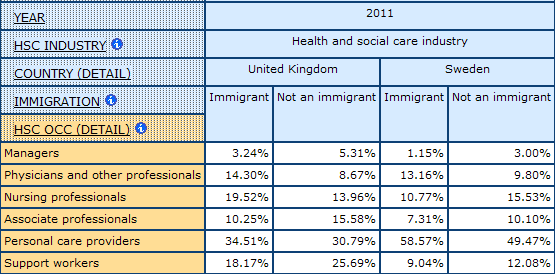

The division of labour among immigrants varies for the two countries in this demonstration. Among all immigrants working in health and social care in the UK, most are concentrated in personal care provider occupations, but many are also concentrated in nursing occupations (Table 5 and Chart 5). Meanwhile, in Sweden, over half of all immigrants working in health and social care are working as personal care providers (58.5%) and fewer are working in all other occupational categories as compared to concentrations found in the UK. In other words, immigrants work in different types of care work in the UK and Sweden reflecting to some extent both different both different immigration policies and professional requirements.

Table 5: Occupational Division of Labour among Immigrants in HSC, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

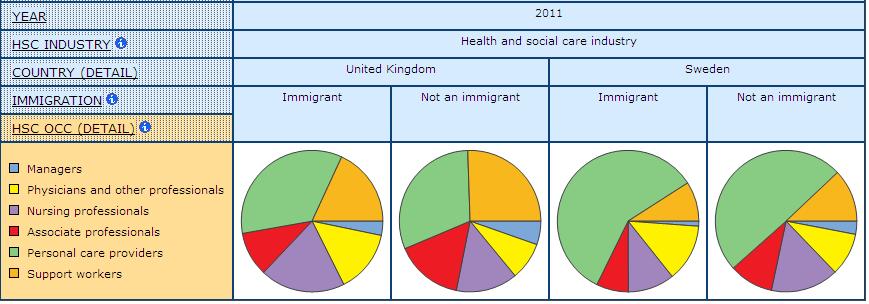

Chart 5: Visualization of Table 5, Occupational Division of Labour among Immigrants in HSC, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

Source: CPD table HSC DE-9

This demonstration reveals the gendered and racialized division of labour in health and social care in the UK and Sweden and how this differs between the two countries. The division of labour in the UK is more “task differentiated” rather than “integrated” as it is in Sweden, borrowing the description of division of labour in long-term residential care used by Daly and Szebehely (2012). This may have implications for the working conditions experienced by workers in these two countries. Women outnumber men in health and social care in both countries but higher concentrations of men are found among physicians and other professionals, though in Sweden, women show larger shares in these occupations. Immigrants are distributed among different types of care work in the UK and Sweden. In the UK, large concentrations of immigrants work as nursing professionals but in Sweden very large concentrations of immigrants work as personal care providers. Other resources of the CPD, such as the library tool, provide links to research that can help shed light on patterns such as these in the statistical data. Our next demonstration reinforces the relevance of the gendered and racialized aspects of work in health and social care with a review of precarious employment among nursing professionals and personal care providers in the UK and Sweden.

DEMONSTRATION 3

Precarious employment in health and social care

This demonstration examines differences in precarious employment among nurses and personal care providers in the UK and Sweden. To measure precarious employment we use several indicators of work context and care conditions including income, form of employment, work schedule, disability and illness and absenteeism.

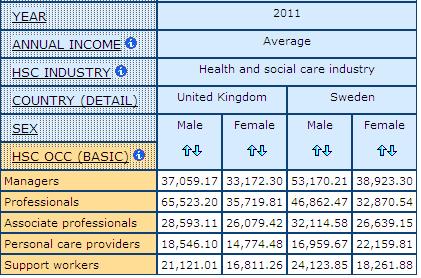

Not surprisingly, we find much lower average annual incomes among personal care providers than among the other occupational groups in health and social care in these two countries (Table 6). For example, female personal care providers in the UK earn an average annual income of only 14,774 Euros and the income gap between these women workers and those working as professionals in health and social care is over 20K Euros. The income gap between women in these two occupations in Sweden is much smaller, at only 10K Euros. Men earn more than women in both countries for all occupations except among personal care providers in Sweden, where women earn more than men. Looking at income, women workers in personal care provider jobs in Sweden are less precarious than those in the UK. Unfortunately, we cannot get information on the average annual income for nurses in Europe because our data source for income (the SILC) collapses nursing professionals with other professionals.

Table 6: Average Annual Income for Men and Women by HSC Occupation, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC IB-5

Source: CPD table HSC IB-5

Chart 6 shows a visual depiction of the average annual income for men and women in professional occupations and in personal care occupations in the UK and Sweden.

Chart 6: Visualization of Average Annual Income for Men and Women, Professionals and Personal Care, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC IB-5

Source: CPD table HSC IB-5

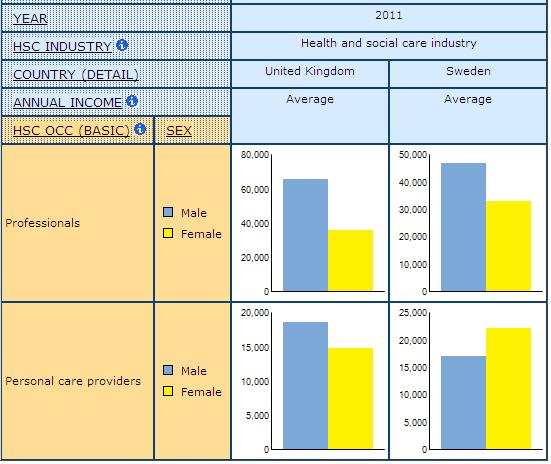

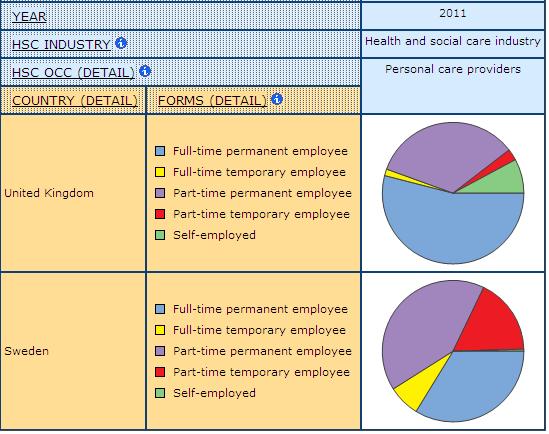

There are differences in the number of nursing professionals and personal care providers who work in more precarious forms of employment such as part-time and temporary between the UK and Sweden. In both countries, more nursing professionals are full-time permanent employees than are personal care providers (Chart 7). However, concentrations of full-time permanent employees are higher in Sweden for both occupations. In the UK a large share of personal care providers are self-employed, while in Sweden, there are almost no self-employed personal care providers. This self-employed health and social care work in the UK is associated with poor working conditions, low pay and few benefits.

Chart 7: Visualization of Form of Employment for Nursing Professionals and Personal Care Providers, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC FE-6

Source: CPD table HSC FE-6

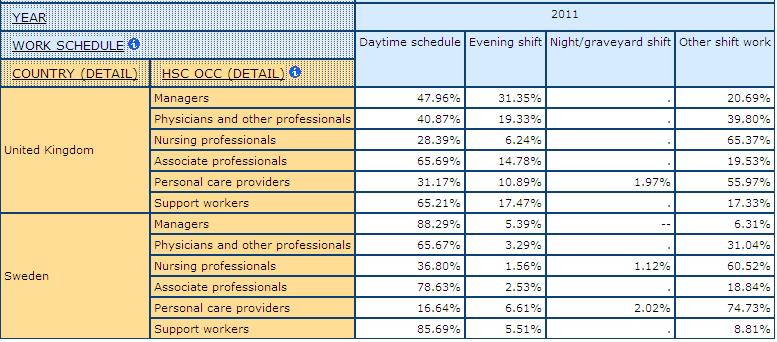

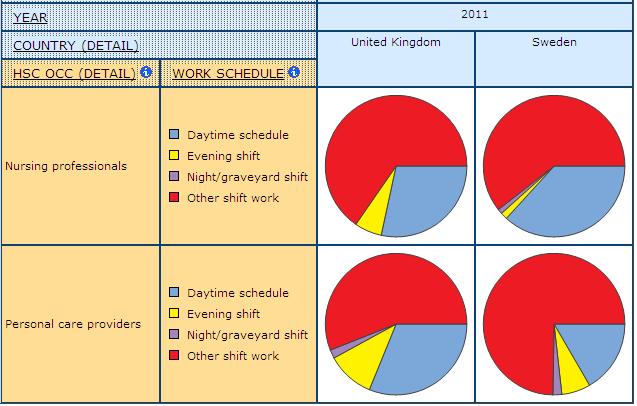

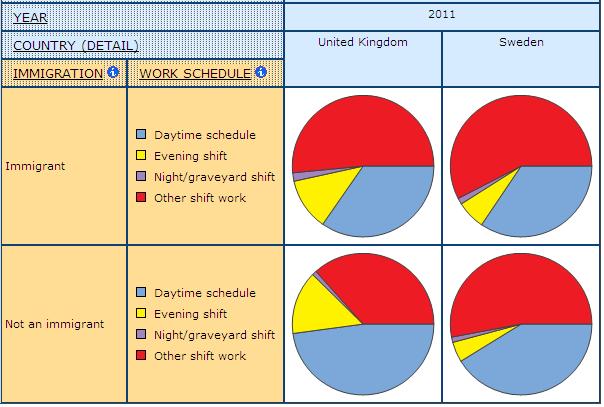

An indicator of precarious employment that is unique to health and social care is work schedule. As mentioned earlier in this conceptual guide, night shifts are associated with higher rates of illness and injury. Further, on-call shifts, a reflection of managerial efforts to coordinate care at peak times, are a detriment to the control workers have in planning their day-to-day lives outside of work commitments. Our variable for work schedules does not provide enough detail to measure levels of on-call, however, there are notable differences between the UK and Sweden in how care work gets scheduled for different occupations and our data suggest these differences are racialized.

Table 7: Work Schedule by HSC Occupation, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Table 7 shows the concentrations of workers in different types of schedules by occupation for the UK and Sweden. For example, out of all managers working in health and social care in the UK, 42.1% work a daytime schedule, compared to 74.4% of managers in Sweden. Large concentrations of many occupations work in “other shift work” which includes rotating and on-call shifts (but most of these workers are likely working on a rotating schedule). In the UK, 63.4% of nursing professionals work in other shift work, compared to 35.6% of physicians and other professionals. Meanwhile, in Sweden, 62% of personal care providers work in other shift work. Chart 8 shows a visual depiction of work schedules in these two countries, comparing nursing professionals with personal care providers. In the UK, more nurses than personal care providers work in other shift, with the reverse true in Sweden. An analysis based on where they work in health services might help us better understand these differences but, as explained above, such comparisons are not possible with these data.

Chart 8: Visualization of Work Schedule for Nursing Professionals and Personal Care Providers, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

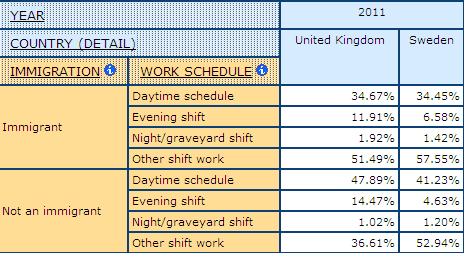

Our CPD data suggest other shift work in both the UK and Sweden is racialized, with higher than average concentrations of immigrant workers. Table 8 shows that among immigrants working in health and social care in the UK, 51.4% work in other shift work as compared to 36.6% of non-immigrants in the UK. Similarly, in Sweden 57.6% of immigrants in health and social care work in other shift work as compared to 52.9% of non-immigrants. Chart 9 shows a visual depiction of the differences in work schedules among immigrant and non-immigrant health and social care workforces in these two countries. Seniority data would help us analyze these data further, but such data are not available.

Table 8: Work Schedule among Immigrants and Non-immigrants in HSC, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Chart 9: Visualization of Work Schedule among Immigrants and Non-immigrants in HSC, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

Source: CPD table HSC WC-14

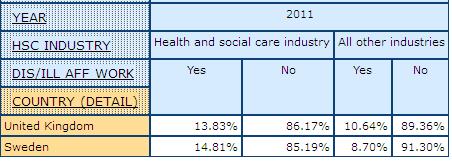

Work in health and social care has many risks and studies show higher rates of injury and illness among health care workers than among other groups of workers (Dabboussy and Uppal 2012). Some occupations are particularly at risk, especially personal care providers and other assisting providers who, in Canada, miss the most days of work per year due to illness and/or injury as compared to other workers in health care (Dabboussy and Uppal 2012). Measuring injury and illness is complicated since some workers may not report accidents for fear of repercussions or be aware that an injury is related to their work (Armstrong et al. 2009). There is a range of indicators of occupational health that are used by researchers, including reported injury and illness and rates of absenteeism. Both are problematic, for example, workers may go to work when sick (referred to as “presenteeism”). Further, workers may use other excuses for absences other than sickness to avoid repercussions. Moreover, sick leave provisions, unionization and other social policies may all influence whether workers report sickness and/or stay home. Our indicators for worker well-being in the CPD include measures of disability and illness affecting work and reason for absences. In both Sweden and the UK, a higher percentage of workers in health and social care as compared to workers in all other industries report that they have a disability or illness that affects their work. Specifically, in 2011, 13.8% of health and social care workers in the UK and 14.8% of workers in Sweden report having a disability of illness affecting their work. This is compared to 10.6% of all other workers for the UK and 8.7% for Sweden (Table 9). This may suggest that workers in health settings in both countries have a greater risk of disability and/or illness that is in related to their work environments.

Table 9: Disability or Illness Affecting Work, HSC Industry and All Other Industries, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC HS-2

Source: CPD table HSC HS-2

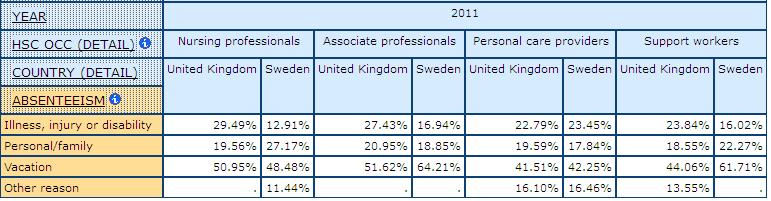

Looking at reasons for absences among the different health and social care occupations, we find that larger shares of workers in some occupations report being absent due to illness, injury or disability (Table 10). For example, in the UK, 26.6% of nursing professionals who were absent during the survey reference week reported illness, injury or disability as the reason. This is compared to only 7.5% of managers and 7.4% of physicians and other professionals in the UK. Fewer nursing professionals in Sweden report this reason for their absence (only 12.9%), however, among personal care providers in Sweden, 23.4% explain an absence as being the consequence of illness, injury or disability. These data align with findings from other studies that health and social care work is risky, associated with higher rates of disability and illness, and that some workers in health and social care are more at risk than others.

Table 10: Reason for Absence by HSC Occupation, UK and Sweden, 2011

Source: CPD table HSC HS-3

Source: CPD table HSC HS-3

Our demonstrations of the health and social care module showcase the navigation features offered within the database, along with the indicators designed to reflect our key concepts. The two analytical demonstrations comparing workers in health and social care in the UK and Sweden show how these indicators can be applied to a particular study. We show that the division of labour in health and social care is gendered and racialized in both countries, but that there are some notable differences in the power experienced by women in these two contexts. Our consideration of precarious employment demonstrates that some workers in health and social care are more precarious than others in both countries. Not surprisingly, personal care providers are among the most precarious workers in care in both Sweden and the UK. However, research on the division of labour in care has indicated that personal care providers in Sweden may be less strained than these workers in other countries because their work is more integrated and they have more control (Daly and Szebehely 2012). Their high rates of absences due to illness and injury may be partially explained by better benefits and more accurate reporting as a result. Further, our own data show that incomes are higher for workers in these occupations in Sweden than in the UK and that there is a smaller gap between the highest and lowest earners in care in Sweden. Immigrant workers in health and social care are also more precarious than other workers in both Sweden and the UK, however, immigrants in the UK are more likely to be concentrated in nursing occupations, while they are more likely to be concentrated in personal care in Sweden. There are limitations to the data available to map health and social care workforces that are highlighted by our demonstrations, in particular the lack of data in our European sources on sector (public, private, for-profit and not-for-profit) and union coverage.

A primary aim of this module is to draw much needed attention to all providers in health and social care, to move beyond typical representations of this work and to offer insight into the context and conditions of work for less visible providers such as personal care and support providers. There has been a shift of focus to including some of these workers in cross-national comparisons. For example, the OECD has begun to include personal care within its statistical investigations of workforces in health and social care. However, the OECD does not provide detail on many of the indicators included within the CPD. Further, there is very little information on the largest group of workers in health and social care settings: support providers. This module is the only source of labour force data where workers in support provider roles in health and social care can be compared cross-nationally.

WORKS CITED

Ali, H. S., and Keil, R. (2008). Networked Disease: Emerging Infections in the Global City. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell Publishers.

Allen, D. (1997). “The Nursing-medical Boundary: A Negotiated Order?” Sociology of Health & Illness, 19(4), 498-529. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.1997.tb00415.x

Allsop, J., Bourgeault, I. L., Evetts, J., Le Bianic, T., Jones, K., and Wrede, S. (2009). “Encountering Globalization.” Current Sociology, 57(4), 487-510. doi:10.1177/0011392109104351

Anderson, J., Beaton, J., and Laxer, K. (2006). “The Union Dimension: Mitigating Precarious Employment?” In L. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 301-317). Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

Armstrong, H., and Armstrong, P. (2004). “Planning for Care: Approaches to Health Human Resource Policy and Planning.” In P. Forest (Ed.), Changing Health Care in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Armstrong, P., et al. (Eds.) (2009). A Place to Call Home: Long Term Care in Canada. Toronto: Fernwood Publishing.