forms of precarious employment

CONCEPTUAL GUIDE TO THE FORMS OF PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT MODULE

Prepared by Leah F. Vosko, Katherine Laxer, Deatra Walsh and Marion Werner

INTRODUCTION

The forms of precarious employment module allows researchers to explore how form of employment relates to precariousness in different places. In an attempt to overcome the dichotomy between “standard” and “non-standard” jobs, and the tendency to conflate the latter with precariousness, its point of departure is that all employment forms should be examined in relation to dimensions of labour market insecurity (see cpd introduction).

The module builds on research highlighting the significance of the growth of so-called non-standard forms of employment and revealing their heterogeneity across nation states. At the same time, it allows researchers to explore dimensions of labour market insecurity within the closest proxy for “standard employment” (i.e., full-time permanent employment). Studies show that considerable variation exists cross-nationally in the relationship between social location (i.e., the interaction of social relations such as gender, “race” and political economic conditions) and form of employment, as well as the effects of particular forms on worker well-being (Danna and Griffin 1999). A further aim of this module is thus to help reveal that linkages between precariousness and specific forms of employment are complex.

The module is organized around three key research questions probing connections between forms of employment and dimensions of labour market insecurity in comparative perspective:

1. What are the dominant forms of precarious employment in different places?

2. How do forms of employment and the extent to which they are precarious differ cross-nationally?

3. How do regulatory contexts and regulatory frameworks, especially those governing employment relations, social location, and industry and occupation shape precarious forms of employment and their variation cross-nationally?

The key concepts section for the module examines employment form along three principal distinctions: the employment relationship (e.g., paid employment versus self-employment), continuity (e.g., permanent versus temporary paid employment), and hours of work (e.g., full-time versus part-time). Rather than assume that any given side of a distinction is necessarily precarious, the module provides users with tools to consider (a) how dimensions of labour market insecurity vary across these distinctions; (b) how dimensions of labour market insecurity vary at their intersections (e.g., part-time temporary employment), and (c) how form of employment and its relationship to precariousness is shaped by workers’ social location and by regulatory context. Translating this approach, elsewhere labeled a mutually exclusive typology of forms of employment (see the precarious employment module of the gender & work database) (Vosko, Zukewich and Cranford 2003), to map onto different labour markets and applying it in cross-national and regional comparisons is a major challenge. In response, the module introduces researchers to key indicators of labour market insecurity in particular places and offers users the tools for comparative analysis.

In addition to the conceptual guide, the forms of precarious employment module allows researchers to explore precarious employment through statistical tables, a searchable library of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources, and a thesaurus of terms. These elements are intended to provide a package of conceptual tools and guidelines for research.

KEY CONCEPTS

The Employment Relationship: Paid Employment versus Self-Employment

Paid Employment

Paid employees are workers who are in an employment relationship: they work for a wage or salary, often for a single employer, on the employer’s premises, and under direct supervision. This subordinate relationship, associated with employee status, was dominant for much of the twentieth century in the countries encompassed in the CPD, forming a central pillar of the SER. Together with continuous employment (described below), it served as a means of achieving workers’ loyalty and willingness to work under direct supervision (or subordination) in exchange for employer support for on-the-job training, job progression and other measures designed to sustain the health and vitality of the worker over the long term (Hyde 1998; Supiot 2001; Fudge et al. 2002; Cranford et al. 2005).

Although paid employees constitute the bulk of the workforce in OECD countries, since the 1970s many industrialized countries have seen a proliferation of forms of employment that “recontractualize” the employment relationship (Mückenberger and Deakin 1989), such that a growing number of workers sell their labour power via commercial or market-mediated mechanisms (e.g., fixed-term employment) rather than through an open-ended employment relationship (Capelli at al. 1997; Gallie et al. 1998; Davies 1999; Engblom 2001; Perulli 2003). Despite the erosion of both the SER as a norm and its closest proxy (i.e., full-time continuous employment), employee status continues to be a prerequisite for workers to access most employment protections and social benefits (e.g., Fudge et al. 2002; Perulli 2003). The continuous employment relationship is thus most closely associated with significant regulatory protection and job certainty. As the subsequent discussion makes clear, however, the presence of an employment relationship does not necessarily mean more secure work (see Forms and Dimensions: A Closer Look, below).

Self-Employment

Self-employment is a heterogeneous category not only because of ambiguities surrounding the employment relationship itself but also because it encompasses both those who work on their own account, or the solo self-employed (SSE), and those who employ others, or self-employed employers (SEE). These two categories often share little in common. SSE can be characterized by high levels of labour market insecurity: in addition to limited regulatory protection, the SSE, particularly women, often experience low degrees of certainty, and lack of control over the labour process (see for e.g., Clayton and Mitchell 1999 on Australia; Sciarra 2005 on EU; Vosko and Zukewich 2006 on Canada; Burchell et al. 1999 on the United Kingdom; and, Hyde 2000 on the United States). While self-employment fell as a percentage of total employment during the mid-twentieth century across the OECD, it grew faster than paid employment in over half of all OECD countries in the 1980s and 1990s, largely in the SSE category (OECD 2000). Australia, Canada and the EU 15 experienced the highest rates of growth in this category among OECD countries and continue to have relatively high levels of self-employment. By 2006, self-employment had nearly doubled in the EU 15, and both Canada and Australia saw the proportion of self-employed workers increase from 10 percent to 16 percent and 15 percent respectively (Custom tabulations based on the HILDA Wave F, the Canadian LFS 2006, and the EU LFS 1983-2006).

The degree to which self-employment is precarious is strongly shaped by workers’ social location as well as by occupation and industry. In the countries included in the CPD, before the late twentieth century, self-employment was a male domain, especially the SEE variety. After 1979, this pattern continued but in some countries a feminization of self-employment occurred as growth rates for women outpaced those for men. Furthermore, in countries such as Australia and Canada, women’s increased shares in self-employment were most pronounced in the SSE variety. In the same period, self-employment was also common among immigrants, especially men, in these countries (on Canada, see for e.g., Frenette 2002). Self-employment cuts across industries and occupations. However, in such countries, the gendering of self-employment largely coincides with existing patterns of occupational and industrial segmentation and associated income polarization.

Continuity: Permanent versus Temporary Employment

Permanent Employment

Permanent employment refers to a continuous (i.e., open-ended) employment relationship, typically between a worker and a single employer, and is another key pillar of the SER. In general, permanent employees benefit from predictable working conditions, such as regular hours, and wages, and often enjoy employer-provided benefits and entitlements, leave provisions, and access to supplementary training (Streeck 1992). Permanent employees are likely to be covered by most basic employment standards governing minimum wages, hours of work, leaves etc. and, depending on the number of hours worked (see Hours below), to be eligible for a range of statutory protections and social benefits (e.g., unemployment insurance). Nonetheless, workers in permanent jobs may lack control over the labour process and earn low wages. Indeed, the quality of many permanent jobs has declined along these dimensions of precariousness (see for e.g., Campbell 2008 on Australia; Vosko 2010 on Canada; and Bernhardt and Marcotte 2000 on the US) (See Forms and Dimensions: A Closer Look below).

Temporary Employment

Temporary employment falls into four principal categories that may overlap: agency, fixed-term or contract, seasonal, and casual employment. The prevalence of these categories varies in different places. Temporary agency work involves a triangular employment relationship where an employment agency mediates between an employer and a worker. For most of the twentieth century, it was restricted by law in many OECD countries; its prevalence today in most of the labour markets covered by the CPD is strongly associated with regulatory changes extending legitimacy to temporary help agencies (Parker 1994; Vosko 2000; Ward et al. 2001; Coe et al. 2007; Houseman et al. 2001).

Fixed-term or contract employment refers to an employment relationship with a specified end date. In the EU, it is the most prevalent form of temporary employment (see also Campbell and Burgess 2001). In that context, its importance in the labour force has ebbed and flowed with changing regulations, such as the adoption of a Directive on Fixed-Term Work in 1999.

A third subset of temporary employment is seasonal work, where employment occurs at particular times of the year. Seasonal work is often grouped with fixed-term work. However, it has distinct features. While formally “temporary”, seasonal workers, including many international migrants, may work for the same employer season after season in sectors such as resource extraction, agricultural production, and tourism (Bardasi and Francesconi 2004; Basok 2004; McDowell et al. 2007; MacDonald 2009). Seasonal employment tends to be a stable feature of particular industries and occupations. In Canada, for example, it is concentrated in the construction and resource sectors, and associated with sales and service occupations, as well as trades, transport and equipment operations (Fuller and Vosko 2008). The stability of seasonal employment depends on the organization of the industry employing seasonal workers and, in the case of resource-based industries, environmental factors (Sinclair et al. 2009).

In countries such as Canada (Galarneau 2005) and the United States (Contingent Work Supplement), casual or on-call employment generally refers to work that is intermittent, lacking a regular schedule. The meaning of casual employment in Australia is different, however. Rather than a definition linked to the presence or absence of a regular work schedule, in Australia casual employment functions effectively as a status in employment; here, casual employment is an employment relationship where the worker lacks the full range of rights and entitlements associated with full-time paid employment (e.g., annual leaves) (Campbell and Burgess 2001). Casuals in Australia may be employed intermittently, but they may also have a regular schedule. They may work on a fixed-term or on an ongoing basis, and they may also be employed through a temporary help agency. To compensate for their insecurity, casual workers receive a premium known as casual loading (Stewart 1992; O’Donnell 2004; Watson 2004; Pocock 2006). Casual employment is more common than other types of temporary employment in Australia.

All of these types of temporary employment – agency, fixed term, seasonal, and casual – are by definition precarious along the dimension of certainty. The link between particular types of temporary employment and other dimensions of precarious employment varies by regulatory context and especially the dominant regulatory framework governing the employment relationship. For example, in EU 15 countries, Canada, and the United States, many temporary agency workers have limited access to statutory and social benefits (because of their short job tenures), low wages, and lack access to control over the labour process through a collective agreement. Fixed-term workers in Canada and the United States also emphasize such issues, for example, in Canada, changes in “employment insurance” following neoliberal reforms in 1996 reduced the chance that unemployed seasonal and temporary workers would qualify for benefits (MacDonald 2009; Vosko and Clark 2009; Vosko 2012). In contrast, fixed-term workers are better protected in countries belonging to the EU due partly to the adoption of an EU Directive on Fixed-Term Work (1999), which regularized this form of employment in exchange for limiting its associated insecurities. After this supranational regulation came into force in 2004, limits on the duration of successive contracts and mechanisms for conversion into permanent employment became mandatory (EC 2006).

Temporary employment has been on the rise since the mid-1980s (OECD 2002). Non-citizens make up a significant number of temporary employees in many of the EU 15 (Ambrosini and Barone 2007: 33). As several tables in the CPD show, the shares of men and women in temporary employment vary by country in the EU 15, but generally speaking, women make up a higher proportion of those in temporary jobs in countries that have high instances of temporary employment in service and retail trade sectors (i.e., Germany, Denmark, Spain and the United Kingdom), and men make up a higher share in countries that have a strong presence of temporary employment in goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing and construction (i.e., Austria, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands).

Hours of Work: Part-time versus Full-time Employment

Our final distinction concerns the difference between full- and part-time paid employment, and hours worked by the self-employed. This distinction is particularly relevant to the dimensions of labour market insecurity of income level and regulatory protection. Part-time workers earn lower incomes because they work fewer hours. In addition, they often earn less because they are segregated in lower paying jobs and low-paid sectors (Rubery and Fagan 1993, 1994; Baxter 1998; Rubery 1998). Full-time employment is strongly associated with the SER and continues to set the standard for accessing employment-related protections and benefits (see Bosch 2006; Vosko 2010). In general, part-time employees receive fewer social benefits and protections from both their employer and the state than their full-time counterparts (Doudeijns 1998; see also contributions to O’Reilly and Fagan eds. 1998). Similarly, where they have access to benefits, many part-time self-employed, especially the SSE, derive them from a spouse (for an e.g., Hughes 1999 on Canada; Vosko and Zukewich 2006).

The number of hours required to be considered full-time or part-time is determined by laws and policies and varies cross-nationally. For example, jobs that involve 35 hours per week are defined as full-time in France whereas in the United States, 40 hours per week is the threshold. Official definitions do not tell us the full story, however. Considerable variation exists in the average hours worked in part-time paid employment across countries. This variation is related not only to the efforts of employers to flexibilize working time, but also to a variety of actions by governments to promote part-time work towards different social ends (Bosch et al. 1994; Tilly 1996; OECD 1998; Rubery 1998; Bosch 1999). In Denmark, for example, the government promoted reductions in full-time working hours in the 1990s in order to achieve a more equitable distribution of paid and unpaid work among men and women, leading to a degree of convergence in part-time and full-time working hours (Bosch 1999; Jackson 2006). In other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the government promoted part-time paid employment to raise employment rates, especially among women. As a result, part-time paid employment in Britain is associated with short hours and occupational and industrial sex segregation (Bosch 1999; Boulin et al. 2006). In some countries, such as the United States, short-hours part-time paid employment can also correlate with multiple job-holding. Workers who hold multiple part-time jobs may effectively work full-time hours, but be prevented from accessing benefits and promotional opportunities because of their employment status as part-timers (Carré and Heintz 2009). Although the number of hours of employment is usually the determinant of regulatory protection, income levels can also serve this purpose. In Germany, for example, reforms passed in 2003 mandated that part-time workers who earn more than 400 Euros per month receive pro-rated social security benefits; those earning less than this threshold – so-called “mini-job holders” – were excluded. Because these workers are exempt from social security contributions and some taxes, this form of low-paid part-time paid employment effectively subsidizes the low-wage sector of the German economy (Weinkopf 2009).

Women are universally overrepresented in part-time employment across industrialized countries, although the extent and form of part-time employment and women’s participation in it differs cross-nationally (Fagan and O’Reilly 1998) and according to the life course. These differences are shaped by the gender contract and the regulatory context, reflecting prevailing forms of household organization, cultural attitudes and norms, and labour laws, policies and practices (Ibid.). For example, only one-quarter of women employed in the United States in the mid-1990s worked part-time, compared to 44 percent of women in the United Kingdom and Sweden, and 66 percent in the Netherlands (Rosenfeld and Birkelund 1995; O’Reilly and Fagan 1998). The challenge for researchers is to account for such divergences in women’s work patterns. One hypothesis put forward to explain the low rates of women’s part-time employment in the United States is that it is particularly undesirable in a country where health insurance is employer-based and is unlikely to be extended to part-time workers (Rosenfeld 2001).

In general, then, the “choice” to engage in part-time paid employment and part-time self-employment is highly conditioned by the prevailing gender contract and regulatory context. For example, in the United Kingdom in 2005, 80 percent of women in part-time employment (as compared to 41% of men) said they did not want to work full-time due to their unpaid work commitments in the household and their desire to spend more time with family. These figures reflect gendered expectations of household duties and the possibility for workers to find jobs that have work schedules that accommodate care-giving (O’Reilly et al. 2009). Similar issues arise when we consider part-time solo self-employment. In Canada, for example, time-related reasons (including concerns with balancing work and family, flexible hours and the possibility to work from home) were the main reason given by female, part-time SSE for their choice of work arrangement, as opposed to their male counterparts whose number one reason was their desire to pursue entrepreneurship (Vosko and Zukewich 2006).

Involuntary part-time employment and involuntary solo self-employment can be indicators of underemployment and used to represent those workers who would like more hours but cannot find jobs that will hire them for more time. Involuntary part-time workers are often excluded from official estimates of unemployment. In Sweden, this group of workers is referred to as the part-time unemployed and covers people who wish to have more hours while remaining part-time and those seeking, but unable to find, full-time jobs. Women represent two-thirds of workers falling in this category, reflecting persistent gendering of care work despite relatively generous state-provided benefits for childcare (Jonsson and Nyberg 2009 on the United States; see also Carré and Heintz 2009).

Forms and Dimensions: A Closer Look

The three distinctions outlined thus far – the employment relationship, continuity, and hours of work – provide different entry-points into the relationship between forms and dimensions of precarious employment. In this section, we look at two examples that deepen our analysis of this relationship by exploring the heterogeneity that exists within these distinctions and at points where they intersect.

Precarious Self-Employment

There is widespread recognition that the distinction between paid employment and self-employment is becoming more porous in many OECD countries (Burchell et al. 1999; Clayton and Mitchell 1999; Fudge et al. 2002, 2003; Perulli 2003; Tham 2004; Weiler 2004; EC 2006b). Although generally recognized as a less secure form of employment (along the dimension of certainty), self-employment is often assumed not to be precarious because the self-employed are presumed to be entrepreneurs with access to capital and who own their own tools. Yet many self-employed people are dependent on the sale of their labour power. Many also perform work personally (i.e., they do not employ others) and their income is often drawn from very few “clients” (Perulli 2003; Sciarra 2005). Moreover, the relationship between a “self-employed” worker and his or her “client” can be on-going (Ibid.). Taken together, these features resemble those associated with paid employment. However, as “self-employed workers” (Cranford et al. 2005), these individuals do not benefit from the same degree of regulatory protection.

Policy-makers have long recognized this gap in regulatory protection, and in some countries, they have sought to extend protections and benefits to some self-employed workers. In the 1970s, for example, several provinces in Canada extended collective bargaining rights to “dependent contractors” (Arthurs 1965) who were deemed to be economically dependent (Bendel 1982). Similarly, in Italy, workers employed in “continuous and coordinated contractual relations” have been labeled “quasi-subordinate” employees, and extended some benefits and protections such as pension rights (Perulli 2003). In Germany, a similar category has been defined as “worker-like persons” (Daubler 1999; Boheim and Muehlberger 2006). EU-level policy-makers have developed the construct “economically dependent work” to explore possibilities for extending regulatory protections to individuals who are in these kinds of relationships.

Efforts to regulate the gray areas of poor- or non-protection at the margins of the employment relationship have a strong gender component. EU policy experts, for example, recognize that women workers in economically dependent work, a phenomenon akin to disguised employment elsewhere “have fewer chances to improve their position in the labour market” (EC 2006), leading to greater labour market segmentation. At the same time that governments acknowledge the potential precarity of self-employment, policy initiatives promote it as entrepreneurship among immigrants and ethnic minorities. This strategy reveals how self-employment and its ambiguous character can unwittingly serve to further marginalize groups facing racism and other forms of discrimination by shutting them out of more secure employment relationships (EC 2004). To date, protections for so-called economically dependent workers in EU countries remain patchy at best, leaving many self-employed workers to face high levels of labour market insecurity, particularly along the dimension of regulatory protection. Furthermore, the self-employed face more variable income levels than their employee counterparts and greater income polarization (Robson 1997; Firebaugh 2003). Although self-employed income is more difficult to measure, studies undertaken in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France found that self-employed income declined in the 1990s relative to that of paid employment (see OECD 2000). In analyzing data in this module, researchers can take into account the diversity of relationships that may exist in the “self-employed” category and related dimensions of insecurity. Harmonized tables drawing on surveys that distinguish between SSE and SEE allow users to analyze indicators of labour market insecurity such as income level and access to benefits for the SSE, those most likely to be in an economically dependent, or quasi-subordinate, employment relationship.

“Permanent” Full-time Employment

Scholarship on precarious employment emphasizes its prevalence not only in so-called nonstandard jobs but also in full-time continuous employment, the closest proxy to the SER (see Multidimensional Approach). The United States provides a particularly important case for analyzing labour market insecurities associated with this form of employment. In the EU 15, Canada and Australia, the share of full-time paid employment in the labour market declined over the last three decades. However, it remained relatively stable in the United States over the same period, and actually increased slightly in the middle of the 2000s (see Vosko 2010: Table 3.1). This does not mean, however, that the United States labour market is less precarious because of the relative prevalence of full-time jobs. In fact, scholars have documented substantial erosion of labour market securities for full-time paid employees in the United States along each of the four main dimensions that the CPD enables users to explore.

Workers in full-time paid employment in the United States experience considerable uncertainty in their jobs. The legal foundations of this uncertainty rest in the lack of statutory protections against dismissal, or what is, in legal terms, called “at-will employment.” At-will employment means that any worker can be legally discharged “without notice for good reason, bad reason or no reason” (Commission for Labor Cooperation 2003: 26). Union power and internal labour markets can buffer workers from at-will employment and have done so historically in the United States; however, both have declined in recent years, increasing the share of workers subject to at-will employment (Hyde 1998; Summers 2000). Increasing uncertainty can be measured through one of its effects: decreasing job tenure, that is, jobs held for shorter lengths of time. From 1983 to 2002, as Stone (2004: Table 4.1) shows, the median job tenure for men in the United States declined dramatically, especially in industries such as manufacturing that were highly unionized and dominated by firms that supported internal labour markets. Depending upon the measure used, women’s job tenure, on the other hand, either grew moderately or was relatively steady over the same period and far below that of men’s, reflecting women’s historical exclusion from continuous employment (Ibid.). For more on job tenure, see the temporal and spatial dynamics module.

Control over the labour process, income level, and regulatory protection have also eroded for workers in the United States in full-time ostensibly permanent employment over the late twentieth and early twentieth-first centuries. Loss of control over the labour process is illustrated by declining unionization rates from 20.1 percent among all wage and salary employees in 1983 to 12.1 percent in 2007 (Walker 2008: 29). Employee wages have stagnated: since the early 1970s, gains in hourly wages were practically nil until the second half of the 1990s, leveling off again and declining slightly in the 2000s (Mishel et al. 2009: Table 3.1). Although increases in annual incomes have occurred, this is because American workers have increased their hours of work, not their wages (Ibid.). Finally, many workers in full-time continuous employment are ineligible for employer-provided entitlements, especially health insurance. In 2005, 14.9 percent of full-time continuous workers were either not offered or deemed ineligible for employer-provided health insurance in the United States (Ibid.: Figure 7E).

INDICATORS

The key concepts related to this module can be divided between two indicator sets: “Forms of Employment” and “Regulatory Protection, Social Wage/Benefits, and Income”. Together, these sets of indicators can be used to identify elements of employment precariousness.

Indicators of Forms of Employment

The first set of indicators include a combination of variables that examine labour force status and the three principal distinctions of the forms of employment – full-time or part-time, self–employed, and temporary or permanent (FE6G1; FE6G2; FE6G3; FE6G4).

Labour force status (FE1G1), divided into “employed”, “unemployed” and “not in labour force”, offers a general view of labour force participation. This can be explored in more depth through variables which distinguish among the specific forms of employment noted above. The CPD includes variables which measure each of these forms in succession (FE3-FE6), with each employment form having several variations. For example, FE3 has three variations: one that reflects a survey definition of full- or part-time employment (FE3G1) and the remaining two specific to hours of work (FE3G2; FE3G3).

Employment Relationship: Employee vs. Self-Employment

Self-employment is one type of employment relationship, and is represented through “self-employment” indicators. These variables aim to classify an individual’s employment by class of worker through which delineations are made between wage and salary employment, self-employment, and unpaid family work. Eurostat, for example, defines the self-employed as “persons who are the sole owners, or joint owners, of the unincorporated enterprises in which they work, excluding those unincorporated enterprises that are classified as quasi-corporations” (Eurostat 2001). Self-employed persons also include the following categories: unpaid family workers, outworkers, and workers engaged in production undertaken entirely for their own final consumption or own capital formation, either individually or collectively. Although the EU LFS collects data on whether a self-employed worker is with or without employees, Eurostat does not release these data in its anonymised datasets used for the CPD.

In the Australian HILDA, the definition of self-employment deviates from that used in many surveys conducted by the Australian Bureau of Labour Statistics (ABS). The ABS definition includes self-employed incorporated workers (owner-managers) as employees (employees of the incorporated entity). The HILDA separates the self-employed into two categories: “employee of own business” and “employer/self-employed” to allow researchers to generate statistics that subscribe to the ABS definition or to create a larger “self-employed” category.

The United States CPS collects data on whether the self-employed are incorporated or unincorporated. However, it is impossible to differentiate between the solo self-employed and self-employed employers through this survey. Additionally in the CPS, individuals responding that they were employed by government, a private company, or a nonprofit organization are classified as wage and salary workers. Persons who respond that they are self-employed are asked, “Is this business incorporated?” Those who respond in the affirmative are also classified as wage and salary workers. In contrast, the “nays” are the self-employed. The rationale for classifying the incorporated self-employed as wage and salary workers is that, legally, they are the employees of their own businesses (Bregger 1996). This approach is a comparable approach to the Australian method of delineating self-employment.

Where available, the CPD includes whether the self-employed are employers (SEE) or solo self-employed (SSE); as well as whether they are incorporated or not. The surveys collect and/or release various degrees of related information. The harmonized variables that reflect self-employment specifically are FE5G1, FE5G2, and FE5G3.

Continuity: Permanent vs. Temporary Paid Employment

Measuring continuity depends upon an understanding of temporary and permanent employment, as each has different cultural and political meanings in different countries, and is therefore operationalized differently. The harmonized CPD tables present a conceptualization of temporary and permanent employment attentive to these social and cultural meanings (e.g., temporary is equivalent to fixed-term, contract, and seasonal work as well as includes training contracts and apprenticeships in the EU).

In Canada, temporary refers to employment of uncertain duration. It is further broken down into four key types of temporary employment: term or contract, seasonal, casual and temporary agency employment. Both Canadian surveys used in the CPD collect data based on these delineations.

The EU LFS also measures temporary employment as employment of uncertain duration. However, the EU LFS definition aggregates all types of temporary employment into one category, which covers fixed-term, contract, and seasonal work, as well as, training contracts and apprenticeships. Other available variables in the EU LFS identify persons whose jobs are temporary because of training, probationary or apprenticeship contracts, offering the option to reclassify these workers as permanent.

The definition and operationalization of temporary employment in the HILDA data is complex. As mentioned above, in Australia, casual and temporary employment can be considered to be “crossed variables”, that is, each is, in part, a subset of the other. In the HILDA data, whether or not a job is temporary is determined by the respondent’s self-identification. At the same time, Campbell (2008) developed a proxy for permanency by combining HILDA variables that measures the presence of leave entitlements for sickness or holidays, two central indicators that employment is not casual. This definition of permanency excludes other casuals who are engaged on an ongoing (though not technically permanent) basis. Were the measure to include all casuals, temporary employment would represent a much greater proportion of total employment in Australia as opposed to the proportion counted using this harmonized variable.

Adding to the complexity of the harmonization process, the United States CPS, in principle, does not distinguish between temporary and permanent employees and formally considers all employees to be temporary.

The harmonized variable, FE4G1 is the most general indicator of whether one’s job is permanent or temporary, although other variables also include a permanent or temporary dimension. This is applicable to FE6G2, FE6G3, FE6G4.

Hours of Work: Full-time vs. Part-time Employment

All the data sources used in the CPD allow researchers to distinguish between full- and part-time employees. However, the distinction between full- and part-time paid employment is drawn differently across countries. The definition of full- and part-time paid employment depends upon how laws and policies define them. As a result, there is definitional variety across countries and therefore national and supranational surveys. This is reflected in the various ways in which data are collected about the full- or part-time status of respondents.

In all countries included in the CPD, the distinction between part-time and full-time is based on the number of hours an individual works per week. For instance, in most laws and policies in Canada, part-time paid employment is defined (explicitly or implicitly) as working fewer than 30 hours per week. In contrast, it is defined as working fewer than 35 hours per week in the United States and Australia. Among the EU countries, the distinction between full- and part-time paid employment differs.

Between the relevant surveys, different methods were used to measure full-time and part-time work. In the HILDA, the United States CPS, and the Canadian surveys, the respondent is classified by using the usual number of hours s/he works in his or her main job. However, in the Eurostat surveys, the person is classified as full-time or part-time based on their self-identification as one or the other. These variations should be kept in mind when using FE3G1, which harmonizes based on each survey’s respective definitions.

With the exception of the HILDA, all of the included surveys collect information on the actual number of usual hours worked (see FE3G2 and FE3G3). This variable allows for harmonization across the surveys as a result of the diverse definitions and measurements of full- and part-time paid employment. This is used in the FE6 groupings, which specifically use either 30 or 35 hours a week, as a cut-off for measuring full- or part-time.

Indicators of Regulatory Protection, Social Wage/Benefits, and Income

Indicators of precarious employment are drawn from the CPD’s measures of regulatory protection, social wage and income. Smaller scale employers, measured through establishment size and firm size (WC4G1 and WC5G1) can indicate precarious employment since these workplaces are frequently associated with a lack of regulatory protection (either a lack of enforcement or a lack of regulation). Similarly, workers are exposed to precarious employment when they lack union coverage (measured with WC6G1) since unionized settings typically offer more protection, enforcement and are associated with higher wages and benefits. Regulatory protection and benefit coverage are also acquired through the amount of time a worker has had a particular job. For example, maternity and parental benefits are only available to workers who have worked in a position for a specific duration. This is also the case for vacation time, which increases for workers employed with one employer for a longer period. To indicate precarious employment in this way, the CPD uses low job tenure (WC7G1) and no benefits (IB7G1; IB8G1). Finally, important measures of precarious employment are low wages and income, which the CPD accounts for with several variables (IB1G1-IB6G1; IB9G1; IB10G1). Often, precarious employment is best indicated using several of these indicators together (Vosko 2006). For example, workers with a combination of low wages, no benefits, no union coverage and low job tenure are particularly precarious.

STATISTICS DATABASE

The cross-national comparative statistical tables of the CPD, using the indicators described above, enable researchers to focus on aspects of precarious employment in relation to the module themes. The statistics database can be used to obtain basic information on a topic (e.g., cross-national comparisons of women’s labour force participation) or to examine complex social relations (e.g., gendered precariousness in different countries). The statistical tables are displayed in Beyond 20/20, enabling users to manipulate the data. University and community users doing non commercial research and teaching may access the statistical data. For more information on the data harmonization approach of the CPD, please consult the introduction. Below we have provided links to the statistics database and information on how to apply for access. Following these links we provide three demonstrations of the data available within the forms of precarious employment module using our key questions as guides to showcase CPD indicators.

statistics database

DEMONSTRATION 1

What are the dominant forms of precarious employment in different places?

This demonstration of the forms of precarious employment module addresses the first question posed at the outset of the conceptual guide: what are the dominant forms of precarious employment in different places? We address this question by looking at four countries including Canada, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands. We have selected these countries for a few reasons. Firstly, these four countries differ in ways that demonstrate several of the key conceptual distinctions presented. For example, the United States, where at-will employment exists, provides an example of a country with relatively precarious full-time paid employment comparatively. Australian examples help display differences among temporary workers in different contexts while the Netherlands is a good example of a country where part-time paid employment is less associated with precariousness than in other countries. Canadian data offer very good detail on the self-employed. Finally, a portrait of these countries exhibits the breadth of statistical labour force data available and harmonized within the CPD, since six of the seven surveys used in the CPD are called upon within this demonstration and the next two, including the Canadian Labour Force Survey, the Canadian Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics, the United States Current Population Survey, the Survey of Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia, the European Union Labour Force Survey and the European Union Survey of Labour and Income and Living Conditions.

We begin with an examination of the distribution of workers in the different forms of employment in the four countries. Not all countries collect the same data on forms of employment, in part a reflection of the differing approaches to employment relationships in different contexts. For example, the United States data in the CPD, drawn from the Current Population Survey, does not regularly include a distinction of temporary and permanent employment, which in part reflects the context of at-will employment described earlier.

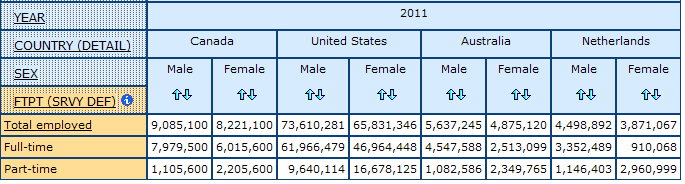

All of the surveys provide the distinction between full- and part-time paid employment, which is defined differently in different countries. The CPD includes a variable that distinguishes full- and part-time paid employment using the survey definition and therefore reflects national context definition, along with variables that distinguish on the basis of hours. The three demonstrations of this module exhibit the survey definition of full- and part-time paid employment. Table 1 provides the counts in 2011 of men and women workers in full- and part-time paid employment in Canada, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands. Also provided in Table 1 are the counts of all employed men and employed women in each country. The United States is the largest of the four countries with a labour force employing over 73 million men and 65 million women. Comparatively, the Netherlands is the smallest country with 4.4 million employed men and 3.8 million employed women.

Table 1 – Full- and Part-time Employment Counts, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-3

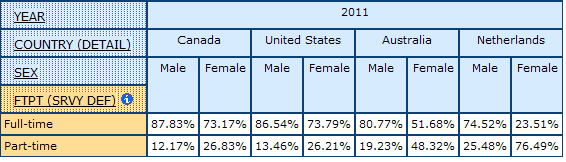

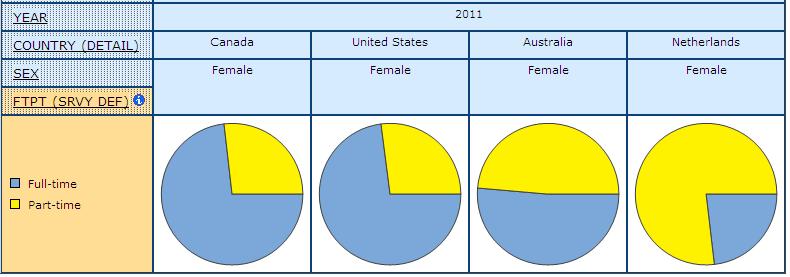

Percentage shares can be calculated within the CPD Beyond 20/20 multidimentional tables. In Table 2 we have calculated shares for men and women in full- and part-time paid employment in the four countries (please see the statistics tutorial for more information on making calculations within CPD tables). In all of the countries, men have larger shares in full-time paid employment relative to women. For example, in Canada 87.8% of men were employed full-time in 2011 as compared to 73.1% of women. Shares of men and women in full- and part-time paid employment are similar to those in Canada in the United States, however, shares are notably different in both Australia and the Netherlands. In both Australia and the Netherlands, fewer men are employed full-time as compared to men in Canada and the United States. Full-time paid employment is also lower for women in Australia and the Netherlands relative to Canada and the United States. In Australia, 51.6% of women were employed full-time and in the Netherlands only 23.5% of women were employed full-time. Chart 1 provides a visualization of these shares of men and women in full- and part-time paid employment in the four countries.

Table 2 – Full- and Part-time Employment Shares, Men and Women, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-3

Chart 1 – Visualization of Full- and Part-time Employment Shares, Women Only, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-3

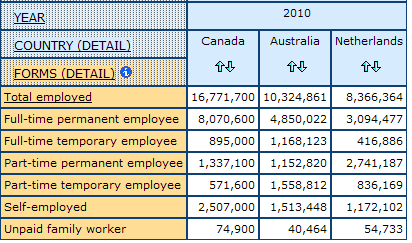

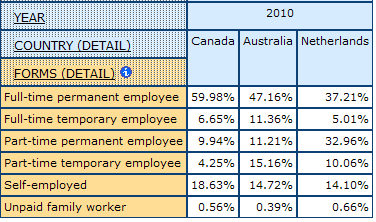

Forms of employment include the distinction between permanent and temporary employment, along with self-employment and unpaid family work. The CPD harmonizes variables to consider these additional forms in relation to full- and part-time paid employment, creating six categories: full-time permanent, part-time permanent, full-time temporary, part-time temporary, self-employment, and unpaid family workers. This harmonization is not possible using data from the United States Current Population Survey, in part a reflection of the different context for employment relationships in the United States. Consequently, we compare only Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands using this typology. Tables 3 & 4 provide a breakdown of forms of employment in these three countries, with Table 3 providing counts and Table 4 providing percentage distributions. The largest shares of workers in all three countries are employed in full-time permanent employment, demonstrating the durability of this form of employment as the norm in many countries. However, in both Australia and the Netherlands, less than 50% of the labour force works in full-time permanent employment, a reflection of the move towards different forms of employment in these countries. In particular, in Australia, 47.1% of all workers are employed in full-time permanent employment, and in the Netherlands the share is only 37.2%.

Table 3 – Detailed Forms of Employment, Counts, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

Table 4 – Shares in Detailed Forms of Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

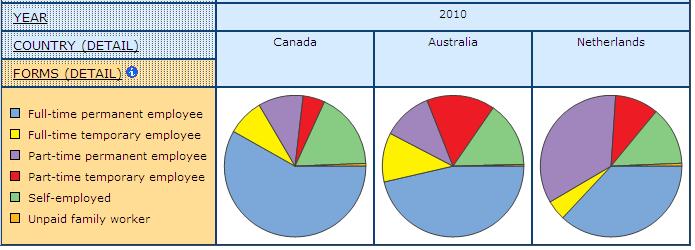

In Canada and Australia the next largest share of workers is in self-employment, at 18.6% and 14.7% respectively. However, in the Netherlands, the next largest share of workers is in part-time permanent employment. Chart 2 clearly demonstrates the different distributions of workers in the different forms of employment in the three countries. Though women are universally overrepresented in part-time paid employment across industrialized countries, the concentration of workers in part-time permanent employment in the Netherlands is shaped by prevailing forms of household organization, cultural attitudes and norms, and labour laws, policies and practices (Fagan and O’Reilly 1998). As noted earlier in this module guide, low rates of part-time paid employment among women in the United States may be related to health insurance coverage which is tied most often to full-time paid employment. Finally, smaller shares of workers are found in temporary employment forms, although in Australia, the temporary forms are more prevalent than in Canada and the Netherlands. Since Australia offers workers a premium known as casual loading for workers in casual employment, employees may find these positions less undesirable because they are partly compensated for the additional insecurity.

Chart 2 – Visualization of Shares in Detailed Forms of Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

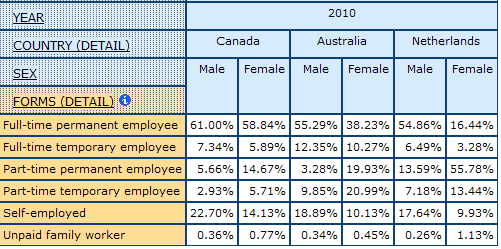

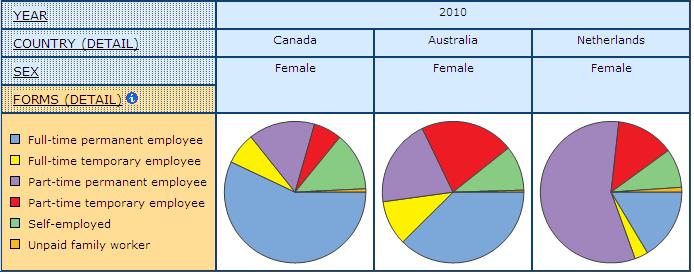

Distributions of workers in the forms of employment differ considerably by sex, though there are notable variations between the three countries profiled in our demonstration. For example, in Canada among both male and female workers, most work in full-time permanent employment. However, more women in Canada work in part-time permanent employment than do men. The pattern is similar in Australia, though overall there are larger concentrations of women in part-time permanent employment in Australia as compared to in Canada. The most striking distribution is found in the Netherlands where only 16.4% of women work in full-time permanent employment and 55.7% of women work in part-time permanent employment. Contrast this distribution with Australia, where 38.2% and 19.9% of women are employed in these two forms respectively. This difference relates to the differences highlighted earlier in this module. Employment patterns for women in the Netherlands are very distinct and standout as a unique national case example of employment in part-time permanent. Once again, we provide a visualization of these varying distributions in the three countries in Chart 3, comparing women in Canada, Australia and the Netherlands in the detailed forms of employment. What surfaces in this particular visualization is the large segment of part-time permanent employment for women in the Netherlands in 2010.

Table 5 – Shares in Detailed Forms of Employment, Men and Women, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

Chart 3 – Visualization of Shares in Detailed Forms of Employment, Women Only, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

Source: CPD table FORMS DE-2

Self-employment can be further broken down into the self-employed who have employees or not, and the self-employed who are incorporated or not incorporated. It is possible to provide a measure of the size of the self-employed labour force in all four countries, but not for employer status or for incorporation status. The remainder of this demonstration is a consideration of these types of self-employment.

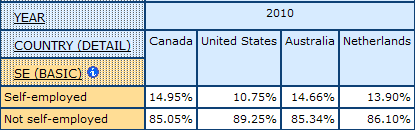

The size of the self-employed labour force in the four countries is similar, with the percentage share between 10-15% in 2010 (Table 6). Australia has the largest share of self-employed workers. Of these four countries, the United States has the smallest share at 10.7% in 2010. Chart 4 provides a simple visualization of these shares.

Table 6 – Self-employment Shares, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

Chart 4 – Visualization of Self-employment Shares, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

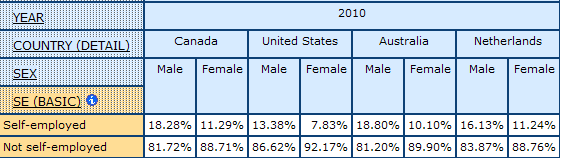

As with the other forms of employment, self-employment is gendered and more men work in this form than women in all four countries. Once again, Australia has the largest share of male workers in self-employment out of the four countries (Table 7). The United States has relatively few women in self-employment, at 7.8% in 2010.

Table 7 – Self-employment Shares, Men and Women, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

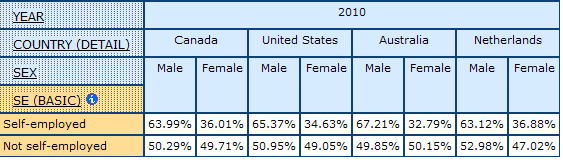

Table 8 provides another set of percentages to analyze the gendered nature of self-employment by providing the concentration of women relative to men among the self-employed and among the not self-employed. For example, out of all self-employed persons in Canada in 2010, 63.9% were men and 36% were women. Percentage shares of men and women among all self-employed persons are very similar in the four countries.

Table 8 – Shares of Men and Women among Self-employed and Not Self-employed, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-8

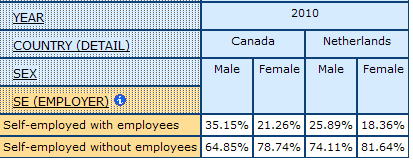

It is possible to compare the self-employed with employees (SEE) and without employees (SSE) for Canada and the Netherlands, but not for Australia or the United States. Out of all male self-employed persons in Canada, 35.1% are SEE as compared to only 25.8% in the Netherlands (Table 9). In other words, Canadian men working in self-employment are more likely to hire employees to assist in their business than men in the Netherlands. Shares of SEE women are very similar in Canada and the Netherlands, and similar too to the shares of SEE men in the Netherlands. In 2010, 21.2% of self-employed women in Canada had employees (SEE) as compared to 18.3% in the Netherlands.

Table 9 – Shares of Self-employed with Employees and without Employees, Men and Women, Canada, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-10

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-10

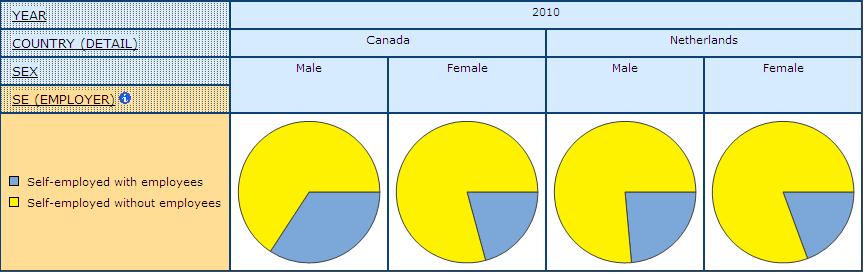

Chart 5 provides the shares of self-employed men and women with and without employees in Canada and the Netherlands in 2010. Here we can easily spot how shares of SEE are similar for men and women in the Netherlands but not for men and women in Canada.

Chart 5 – Shares of Self-employed with Employees and without Employees, Men and Women, Canada, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-10

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-10

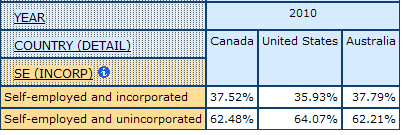

Incorporation status is measured in three of the countries: Canada, the United States and Australia, but Eurostat data do not provide this distinction for the self-employed. The percentage share of self-employed persons with incorporation status is very similar across these three countries. For example, Table 10 shows that in 2010 37.5% of self-employed persons in Canada were incorporated, 35.9% in the United States, and 37.7% in Australia.

Table 10 – Shares of Self-employed with Incorporation Status and without Incorporation Status, Canada, United States, Australia, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

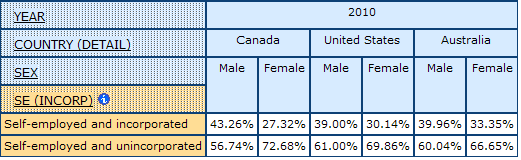

When comparing men and women in self-employment and with or without incorporation status, there are differences between the three countries. Table 11 demonstrates that in Canada in 2010, 27.3% of women self-employed persons were incorporated as compared to 30.1% in the United States and 33.3% in the Netherlands. In considering these distinctions – having employees and incorporation status – Canada presents as a country where men and women differ more in self-employment than men and women in the other countries. Canadian women relative to Canadian men are less likely to have employees and be incorporated. In the other countries, these relative differences between men and women in self-employment (when they can be measured) are smaller.

Table 11 – Shares of Self-employed with Incorporation Status and without Incorporation Status, Men and Women, Canada, United States, Australia, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

To summarize, women tend in all four countries to have higher concentrations in part-time paid employment, however, women in Australia and especially in the Netherlands have much larger concentrations in this form of employment relative to Canada and the United States. Measures for more detailed forms of employment are available in Canada, Australia and the Netherlands, but not in the United States where permanency as a measure has less relevance given the context of at-will employment. Once again, the Netherlands stands out as a country with very large concentrations of workers in part-time paid employment. Finally, we find that concentrations in different types of self-employment are gendered and that women are more likely to work in more precarious forms of self-employment – lacking incorporation status and without employees.

DEMONSTRATION 2

How do forms of employment and the extent to which they are precarious differ cross-nationally?

Our consideration of forms of employment and the extent to which they are precarious in the four countries is the focus of the second demonstration of this module. Here we use several indicators of labour market insecurity and precariousness harmonized in CPD data, including average annual income, job tenure, union status, firm size, and health benefit coverage. We also include a measure of work schedules, described in the indicators section for the health and social care module, since it too is related to aspects of precariousness such as control over the labour process and certainty. Though degree of precariousness differs among countries for these indicators (for example, employer provided health benefit coverage is more important in the United States), we use these indicators as a means to begin to tease out some of the context specific differences that are further explored in the third demonstration.

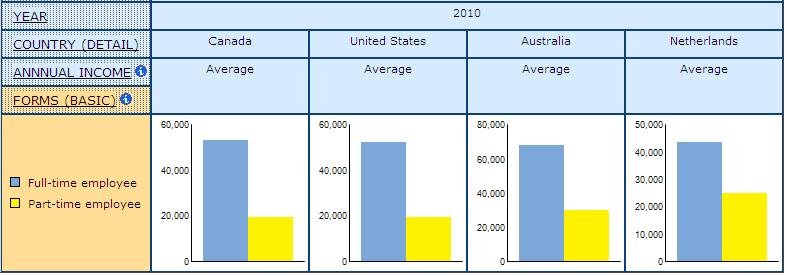

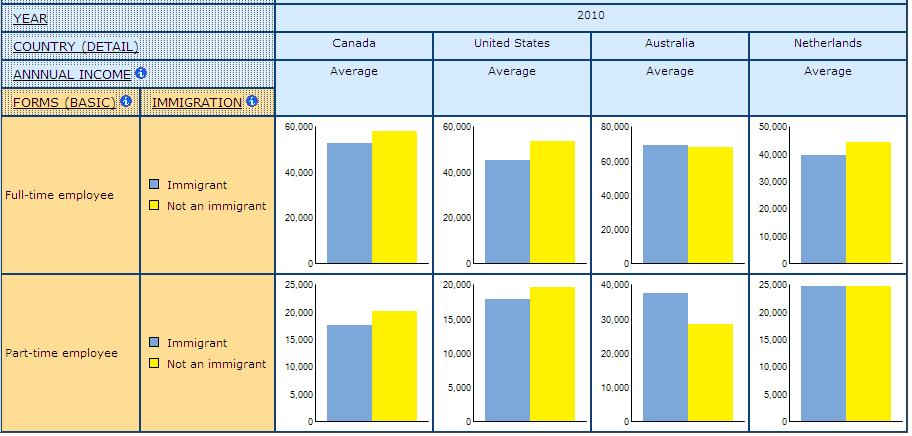

Beginning with average annual income, it is not surprising that part-time paid employees earn less than full-time paid employees in each of the four countries since part-time workers often work fewer hours. However, as Chart 6 shows, the relative difference in average annual incomes is less in the Netherlands, pointing to how part-time paid employment is less associated with precariousness in this country.

Chart 6 – Average Annual Income in National Currency for Full- and Part-time Paid Employees, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-1

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-1

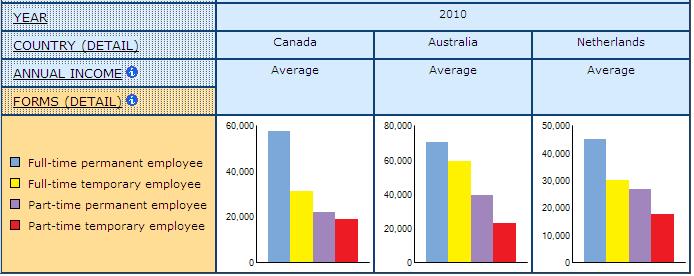

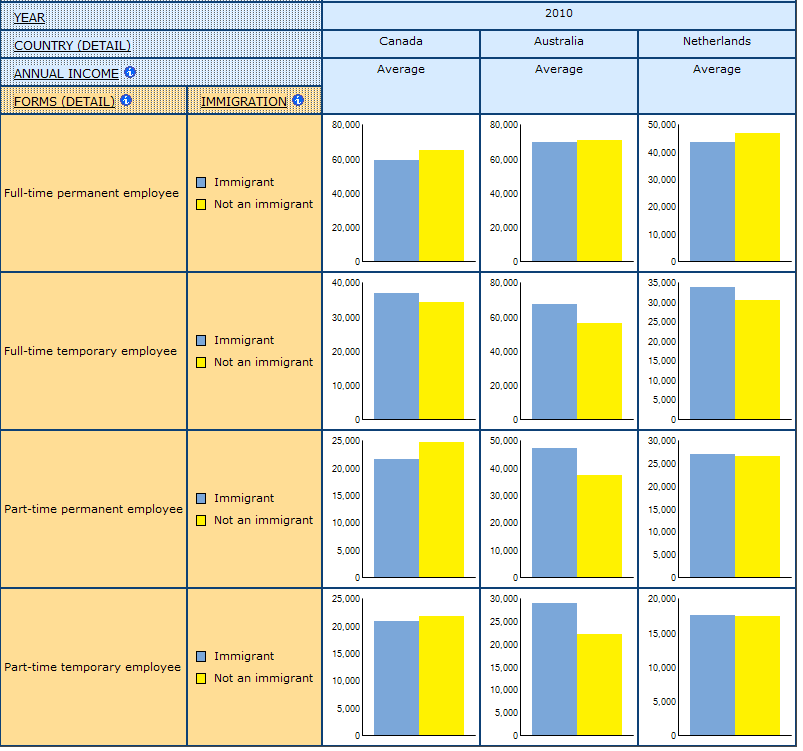

Breaking down employment into more detailed forms unveils additional variation in average annual incomes that can be linked to permanency (Chart 7). Full-time permanent employees earn the most relative to full-time temporary, part-time permanent, and part-time temporary, in Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands. However, the relative difference in average annual incomes for full-time permanent and full-time temporary employees is smaller in Australia than it is in Canada and the Netherlands, a reflection of the casual loading premium paid to workers in casual employment in Australia. Once again, the relatively high average annual incomes for part-time permanent employees in the Netherlands is easily seen in Chart 7.

Chart 7 – Average Annual Income in National Currency for Paid Employees in Different Forms of Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

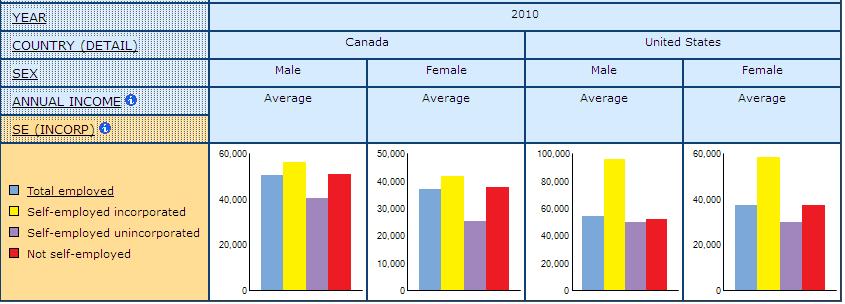

Incorporation status is linked to higher average annual incomes for the self-employed. In both Canada and the United States the self-employed with incorporation status earn more than those who do not have incorporation status, as can be seen in Chart 8. However, the relative difference in average annual income is much larger in the United States. Chart 8 also compares the average annual income of men and women in these employment forms and women earn less than men across all forms but the relative differences are larger in the United States than in Canada. For example, the average annual income for incorporated self-employed men in Canada is approximately $55K and for women it is approximately $41K, a difference of $14K between the sexes. In the United States, self-employed men with incorporation status earn significantly more, approximately $97K, compared to women who early approximately $58K – a difference of $41K.

Chart 8 – Average Annual Income in National Currency for Self-employed by Incorporation Status comparing with All Employed and Not Self-employed, Men and Women, Canada, United States, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

Source: CPD table FORMS FE-9

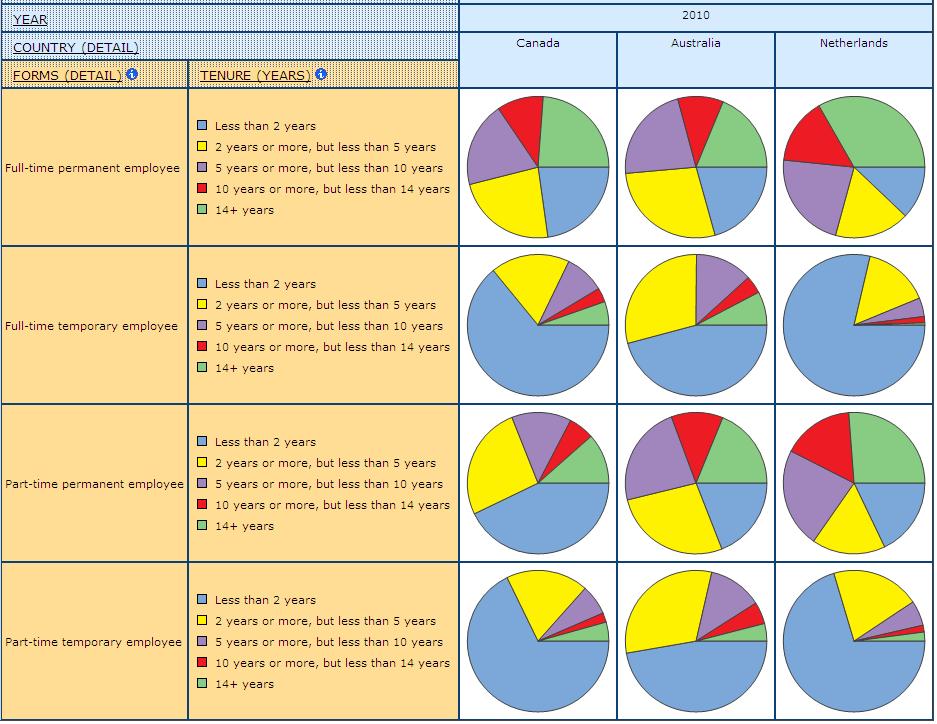

Low job tenure can be an instructive indicator of labour market insecurity and precariousness given that workers employed for shorter periods tend to have less benefit coverage, less experience, and lower incomes than workers with longer job tenure. Not surprisingly, full-time permanent employees have relatively long job tenure when compared to full-time temporary, part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees. Comparing Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands (Chart 9), we see that the largest shares of workers who have been employed for 14 or more years are found among full-time permanent employees. Shares of workers with less than 2 years job tenure are largest among the temporary forms, both full-time and part-time. However, Australian workers in temporary employment have longer job tenures, suggesting that workers in temporary employment stay in their positions for longer in Australia due to the casual loading premium.

Chart 9 – Job Tenure for Paid Employees in Different Forms of Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-5

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-5

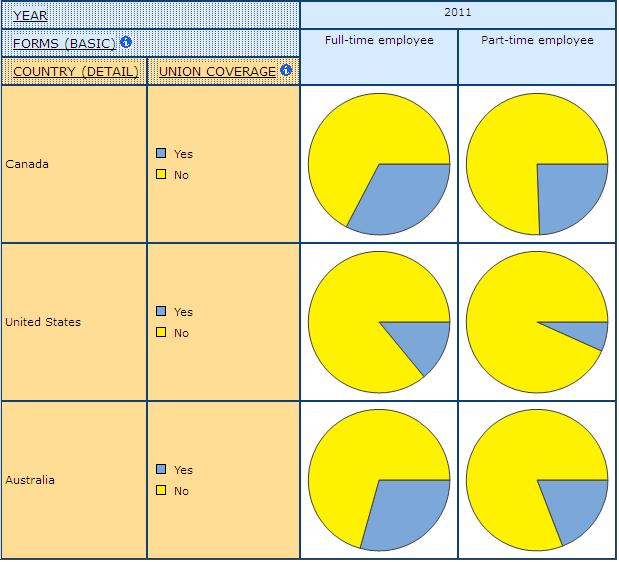

Also an important indicator related to precariousness is union coverage. Employees with union coverage tend to have higher wages, more extensive benefit coverage, seniority entitlements, along with an array of other negotiated benefits such as more sick days and vacation days. The benefits of union coverage are often referred to as the union advantage (Briskin 2010; Jackson 2003). Workers without union coverage are found to be more precarious, particularly in terms of having fewer benefits and less job security (Anderson et al. 2006). Union coverage is associated with form of employment and workers in forms deviating from the once normative full-time permanent position are found to be less unionized. For example, Chart 10 depicts a visualization of union coverage for full- and part-time paid employees in Canada, the United States and Australia in 2011. Though overall union coverage varies in each country and is related to national contexts of collective bargaining, part-time paid employees are less unionized than full-time paid employees in all three countries.

Chart 10 – Union Coverage for Full- and Part-time Paid Employees, Canada, United States, Australia, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-4

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-4

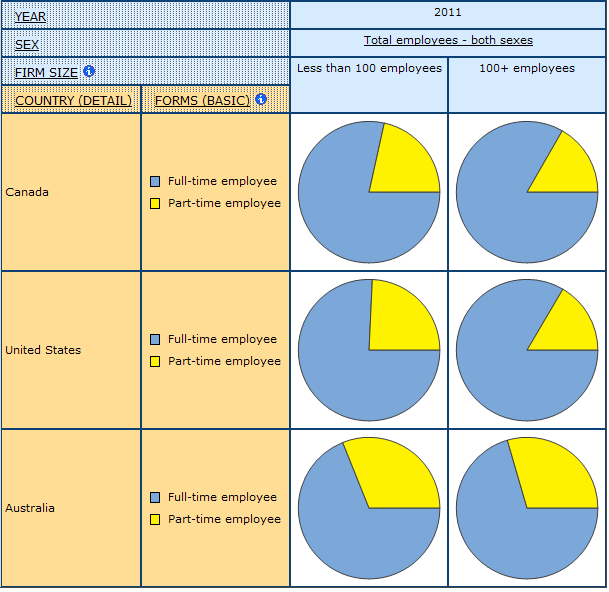

Firm size and establishment size are associated with precarious employment with smaller workplaces tending to provide fewer benefits, less job security, and lower wages. Firm size is an available measure for Canada, the United States and Australia. Forms of employment associated with precariousness, such as part-time and temporary, tend to be more prevalent in small work places. Chart 11 shows that in all three countries in 2011, businesses employing fewer than 100 workers were slightly more likely to employ those workers part-time.

Chart 11 – Shares of Full- and Part-time Paid Employees by Firm Size, Canada, United States, Australia, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-3

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-3

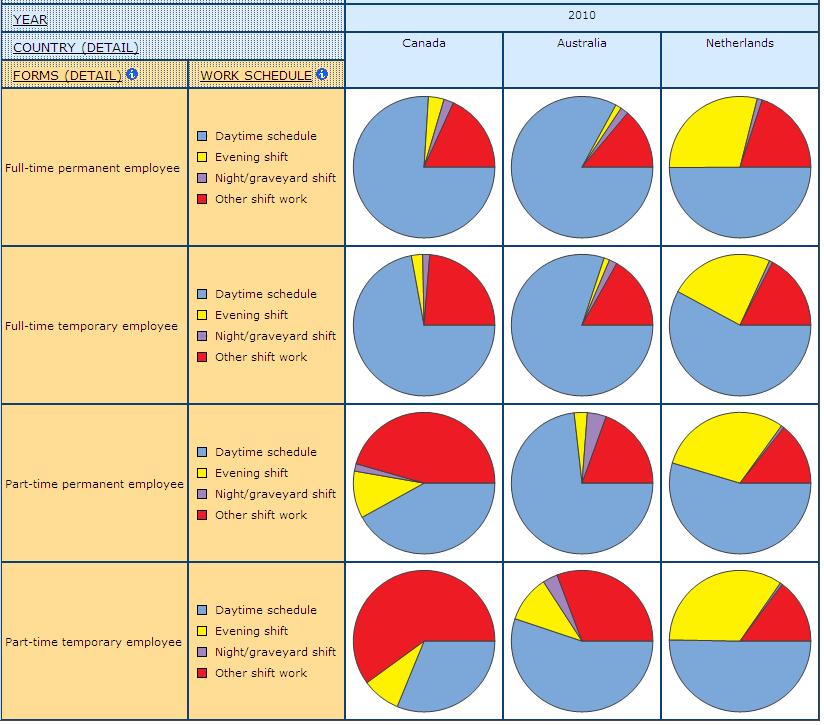

Concentrations of workers in different types of work schedules vary by form of employment and can be measured in several of the countries represented in the CPD, including Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands. The only country in the CPD that does not provide data on work schedule is the United States. Chart 12 reveals that workers in full-time permanent employment in Canada and Australia were more likely to have daytime schedules in 2010. Notably, this was not the case in the Netherlands where full-time permanent employees were less likely than both full-time temporary and part-time permanent employees to work in daytime schedules. Other shift work, which includes rotating schedules and on-call scheduling, are more common in Canada among part-time permanent and part-time temporary employees. Graveyard shifts are the least common type of schedule across all three countries and for all forms of employment, however, Australian workers in both part-time permanent and part-time temporary show higher concentrations in these shifts. Evening shifts are also more common for the part-time forms in Australia, and also in Canada. Once again, the Netherlands deviates from the norm where all forms of employment are associated with very high relative concentrations in evening shifts. For example, in 2010, over a quarter of workers in all four forms of employment were employed in evening shifts in the Netherlands as compared to very small percentages in Australia and in Canada.

Work schedule is linked to precariousness in several ways. Workers with less seniority and less job security tend to be found in shifts that are often impractical and undesirable, including night, graveyard, rotating and on-call shifts. Workers with less leverage than other workers may not be able to select preferred shifts, which tend to be regular daytime schedules. Research indicates that some shifts are dangerous and risky to the health and well-being of workers, particularly night and rotating shifts, which are associated with higher injury rates and higher cancer rates (Wong, McLeod and Demers 2010; Wong et al. 2011). On-call shifts, on the rise among some groups of workers, are a reflection of managerial efforts to reduce costs on labour but have serious implications for how employees can plan their day-to-day lives including family and caregiving responsibilities. This is especially the case for women who tend to have more competing caregiving responsibilities than men, with specific, gendered health outcomes. Some groups of workers are more commonly found in atypical schedules, such as shift and night work, including for example immigrants in health and social care. The health and social care module provides more information on how work schedule is related to precariousness.

Chart 12 – Work Schedule by Different Forms of Paid Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-6

Source: CPD table FORMS WC-6

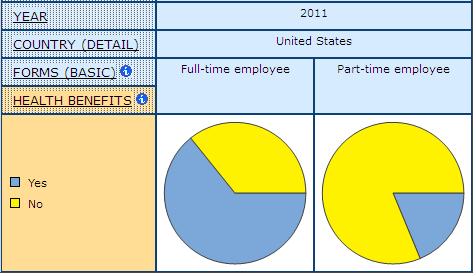

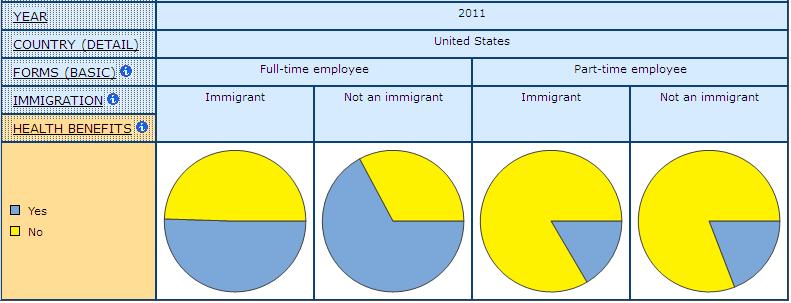

The final indicator of precariousness examined in this demonstration is employer provided health benefit coverage. Health benefit coverage is an especially important benefit for workers in the United States where most health insurance is accessed through paid employment. All other countries in the CPD provide some form universal health care for their citizens, which partly explains why health benefit coverage is not included as a variable in several surveys of the CPD. However, extended health benefits provided by employers supplement for what is often lacking in state provided universal coverage – such as dental care, some forms of hospital care, medications, extended care, home care, among other things – pointing to the importance of this indicator. Further, as governments move towards reducing expenditures on health and social care, state provided universal health plans are providing for less in some contexts (see the module on health and social care).

Health benefit coverage is associated with form of employment. In the United States, part-time paid employees were much less likely to have employer provided health benefit coverage than full-time paid employees in 2011, contributing to their more precarious status overall.

Chart 13 – Health Benefit Coverage for Full- and Part-time Paid Employees, United States, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-8

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-8

To summarize our second demonstration, we use several indicators of labour market insecurity and precarious employment to evaluate differences including average annual income, job tenure, union coverage, firm size, work schedule, and health benefit coverage. Not surprisingly, we find that average annual incomes are linked to forms of employment and that workers in part-time and temporary forms often earn less than workers in full-time and permanent forms of employment. Job tenure is shorter for workers in part-time and temporary employment. Further, union coverage is less extensive for workers in part-time paid employment, and part-time paid employees are more common in smaller firms. Work schedules vary considerably for the countries in our demonstrations and we find that in Canada, workers in part-time and temporary employment are more likely to work in more precarious schedules such as shift work including rotating and on-call. In the Netherlands, form of employment is not linked to work schedules and in general employees show more even distributions across type of schedule with more workers in all forms of employment working in evening shifts. Finally, employer provided health benefit coverage, which is very important for employees in the United States, is much less extensive for workers in part-time paid employment, pointing to the importance of form of employment in this country.

DEMONSTRATION 3

How do regulatory contexts and regulatory frameworks, especially those governing employment relations, social location, and industry and occupation shape precarious forms of employment and their variation cross-nationally?

The final demonstration of this module extends the analysis of the previous two demonstrations by considering how precarious employment is shaped by regulatory contexts and regulatory frameworks that govern many aspects of the labour force including employment relations, social location, and industry and occupation. In this demonstration, we focus on social location, in particular, the social location of immigrants and non-immigrants. Considerable research demonstrates the precariousness faced by immigrants relative to non-immigrants. We explore precarious employment for immigrants relative to non-immigrants and question how precarious employment differs for these categories of workers in Canada, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands.

As has been demonstrated, annual income is related to form of employment and is a strong indicator of precarious employment. Here we ask to what degree average annual income is related to social location such as immigrant status. Further, are annual income and immigrant status linked to form of employment and national context? CPD data suggest that national context and form of employment matter a great deal for employees in different social locations. Chart 14 provides a visualization of average annual income in national currencies for immigrants and non-immigrants in full- and part-time paid employment in all four countries in 2010. For both full- and part-time paid employees in each country, immigrants earn less on average than non-immigrants. However, there are some important variations in this pattern. For example, in Australia, immigrants in full-time paid employment earn on average about the same annual income as non-immigrants in full-time paid employment. Immigrants in part-time paid employment earn more than non-immigrants in part-time paid employment in Australia. The only other country where immigrants earn nearly or equally as much as non-immigrants is in the Netherlands, where part-time paid employees have near equal incomes regardless of immigrant status. The income gaps for immigrants and non-immigrants is largest in Canada and the United States, where, full- and part-time paid employment do not seem to shape the gaps as much as social location.

Chart 14 – Average Annual Income in National Currency for Immigrants and Non-Immigrants in Full- and Part-time Paid Employment, Canada, United States, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

Chart 15 provides a visualization of average annual incomes for immigrants and non-immigrants in the detailed forms of paid employment, a measure available for three of the countries examined in our demonstrations for this module. The addition of temporary and permanent status to the full- and part-time paid employment forms unveils some of the nuanced differences related to national context and forms of employment when social location such as immigrant status is considered. For example, in Canada, immigrants earn on average less than non-immigrants in the permanent forms, but they earn equal amounts in the temporary forms. In Australia, immigrants earn equal incomes to non-immigrants in full-time permanent employment, but they earn more in all three other forms of employment. These variations are related to several things. Immigrants tend to work in different industries and occupations depending on national context and national economic priorities. For example, in Canada in recent years, many immigrants are allowed in to work in specific jobs such as caregiving.

Chart 15 – Average Annual Income in National Currency for Immigrants and Non-Immigrants in Different Forms of Paid Employment, Canada, Australia, Netherlands, 2010

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-11

A consideration of health benefit coverage for immigrants and non-immigrants in full- and part-time paid employment in the United States in 2011 demonstrates how deeply social location can be tied to precariousness. Chart 16 reveals that employees in part-time paid employment are equally likely to lack health benefit coverage in the United States, regardless of immigrant status. However, when comparing employees in full-time work, immigrants are much less likely than non-immigrants to have health benefit coverage.

Chart 16 – Employer Provided Health Benefit Coverage for Immigrants and Non-Immigrants in Full- and Part-time Paid Employment, United States, 2011

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-8

Source: CPD table FORMS IB-8

Several observations that emerge from comparing forms of employment, precariousness and social location for Canada, the United States, Australia, and the Netherlands through the foregoing demonstrations. In our first demonstration we found that concentrations of workers in different forms of employment such as full-time, part-time, permanent, temporary, and self-employment vary by country. In general, women in all four countries tend to have higher concentrations in part-time paid employment. However, women in Australia and especially in the Netherlands have much larger concentrations in part-time paid employment relative to Canada and the United States. Measures for more detailed forms of employment are available in Canada, Australia and the Netherlands, but not in the United States where permanency as a measure has less relevance given the context of at-will employment. The Netherlands stands out as a country with very large concentrations of workers in part-time paid employment. Our consideration of forms of employment ends with an examination of concentrations of workers in self-employment. We find that these concentrations are gendered and that women are more likely to work in more precarious types of self-employment – lacking incorporation status and without employees.

In our second demonstration, we consider how forms of employment are more or less precarious in different contexts. We use several indicators of labour market insecurity and precarious employment to evaluate differences between national contexts including average annual income, job tenure, union coverage, firm size, work schedule, and health benefit coverage. Not surprisingly, we find that average annual incomes are linked to forms of employment and that workers in part-time and temporary forms often earn less than workers in full-time and permanent forms. Job tenure is shorter for workers in part-time and temporary paid employment. Further, union coverage is less extensive for workers in part-time paid employment, and part-time paid employees are more common in smaller firms. Work schedules vary considerably for the countries in our demonstrations and we find that in Canada, workers in part-time and temporary paid employment are more likely to work in more precarious schedules such as shift work that includes rotating and on-call. In the Netherlands, form of employment is not linked to work schedules and in general employees show more even distributions across types of schedule with more workers in all forms of paid employment working in evening shifts. Finally, employer provided health benefit coverage, which is very important for employees in the United States, is much less extensive for workers in part-time paid employment, pointing to the importance of form of employment in this national context.

The final demonstration of this module examined how social location, governed by national regulatory context, shapes precarious forms of employment and their variation cross-nationally. We look specifically at immigrant status and compare the average annual incomes in different forms of employment, along with the health benefit coverage for immigrants and non-immigrants. We find that immigrant status matters more in some contexts and for some forms of employment. Both Canada and the United States present as examples where immigrants often work in less desirable forms of employment associated with more precariousness such as less benefit coverage. The United States provides a very striking example of this where immigrants are as (un)likely to have health benefit coverage as non-immigrants in part-time paid employment, but they are much less likely in full-time paid employment. Immigrants fare better in both Australia and the Netherlands in the different forms of employment where there are smaller gaps in average annual incomes.

The statistical data harmonized in the CPD allow for unique cross-national comparisons. In general, these demonstrations point to the importance of examining differences according to national context, form of employment, social location and precariousness.

WORKS CITED

Ambrosini, M., and Barone, C. (2007). Employment and Working Conditions of Migrant Workers. (No. 74). Dublin: Eurofound, MZES University of Milan.

Arthurs, H. W. (1965). “The Dependent Contractor: A Study of the Legal Problems of Countervailing Power.” University of Toronto Law Journal, 16, 18-117.

Bardasi, E., and Francesconi, M. (2004). “The Impact of Atypical Employment on Individual Wellbeing: Evidence from a Panel of British Workers.” Social Science & Medicine, 58(9), 1671-1688. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00400-3

Basok, T. (2004). “Post-national Citizenship, Social Exclusion and Migrants Rights: Mexican Seasonal Workers in Canada.” Citizenship Studies, 8(1), 47-64.

Baxter, J. (1998). “Will the Employment Conditions of Part-timers in Australia and New Zealand Worsen?” In C. Fagan and J. O’Reilly (Eds.), Part-time Prospects: International Comparisons of Part-time Work in Europe, North America and the Pacific Rim. (pp. 265-281). Psychology Press.

Bendel, M. “The Dependent Contractor: An Unnecessary and Flawed Development in Canadian Labour Law.” University of Toronto Law Journal, 32, 374-411.

Bernhardt, A., and Marcotte, D. E. (2000). “Is ‘Standard Employment’ still What it Used to be.” In F. Carré, M. A. Ferber, L. Golden and S. A. Herzenberg (Eds.), Nonstandard Work: The Nature and Challenges of Changing Employment Arrangements. (1st ed., pp. 21-40). Champaign, Illinois: Industrial Relations Research Association/Cornell University Press.

Böheim, R., and Muehlberger, U. (2006). Dependent Forms of Self-employment in the UK: Identifying Workers on the Border Between Employment and Self-employment. Bonn: IZA Discussion Paper (No.1963).

Bosch, G. (1999). “Working time: Tendencies and Emerging Issues.” International Labour Review, 138(2), 131-150.