precarious employment

CONCEPTUAL GUIDE TO THE PRECARIOUS EMPLOYMENT MODULE

Prepared by Cynthia Cranford and Leah F. Vosko with contributions from Katherine Laxer

INTRODUCTION

The precarious employment module explores the relationship between gender and other social relations of inequality, changing employment relationships and insecurity in labour markets. The module draws on recent research that elevates the concept of precarious employment and examines the gender of precariousness in the Canadian labour force (Fudge 1997; Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003; Vosko 2002b). Statistical tables allow researchers to explore the relationship between: sex/gender; temporary, part-time and self-employment; and limited social benefits, low wages and poor working conditions. The tables are accessible from a number of points within the database. A library made up of a searchable catalogue of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources related to precarious employment, together with a thesaurus of terms, assists researchers in analyzing the data through a feminist political economy lens.

This conceptual guide to the precarious employment module introduces researchers to key concepts in the study of changing employment relationships, and to the data available to examine precarious employment and its consequences for women and men. The guide then demonstrates how researchers can examine precarious employment through both the statistical data and library resources.

KEY CONCEPTS

Evidence of the decline of the standard employment relationship in Canada is growing. The standard employment relationship refers to a situation where the worker has one employer; works full-time, year-round on the employer’s premises under his or her supervision; enjoys extensive statutory benefits and entitlements; and expects to be employed indefinitely (Fudge 1997; Muckenberger 1989; Schellenberg and Clark 1996; Vosko 1997; 2002a). The standard employment relationship became the normative model of (white) male employment in Canada in the post World War II era, yet forms of employment that fall outside this norm and that employ primarily women have grown since the late 1970s (Fudge and Vosko 2001a; 2001b).

While patterns vary, most OECD countries experienced substantial increases in at least one of the following types of employment in the post-1970 period: self-employment, homework, on-call work, part-time work or temporary work (ILO 1999). Nevertheless, the standard employment relationship remains the model upon which labour laws, legislation and policies are based, prompting a correlation between the growth in ‘non-standard’ forms of employment and rising precariousness that is highly gendered (Fudge and Vosko 2001b; Fudge and Vosko 2003; Vallée 1999; Vosko 1997).

The precarious employment module casts attention to dimensions of precarious employment relationships – such as limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, low wages and poor working conditions – and allows researchers to explore how, and to what extent, growing precariousness in the labour market is a gendered phenomenon. A focus on gender and precarious employment goes against the grain. There is a common tendency to group together a broad range of employment forms and work arrangements, unified by their deviation from the standard employment relationship, into a single category of “non-standard” employment. However, heterogeneity and gender differences characterize forms of employment that fall outside the standard employment relationship, making it necessary to examine empirically the relationship between forms of employment and precariousness. This requires interrogating what have come to be normalized descriptive concepts – terms such as non-standard employment – as well as newer concepts, such as contingent employment and atypical employment.

In Canada, the growth of “non-standard employment” became a significant topic of discussion in the 1980s. Harvey Krahn (1991 and 1995) produced the earliest study on the growth of non-standard employment in Canada. Krahn’s measure for non-standard employment was made up of four employment situations that differed from the norm of a full-time, full-year, permanent paid job:

1. part-time employment;

2. temporary employment (i.e., term or contract, seasonal, casual, temporary agency and

3. all other jobs with a pre-determined end date);

4. own-account self-employment (i.e., self-employed person with no paid employees); and multiple job holding.

In Europe, the concept atypical employment was used in much the same way – to refer to all forms of employment and work arrangements that fall outside the full-time permanent norm (Cordova 1986).

In the 1980s, U.S. statisticians advanced the concept of contingent employment. Anne Polivka and Thomas Nardone (1989) argue that the most salient characteristic of contingent employment is temporality. Anne Polivka and Jay Stewart (1996) derive three estimates of contingent employment, applying them to the U.S:

1. all wage and salary workers who do not expect their job to last;

2. wage and salary workers who have worked for their current employer for less than one year; or

3. expect to work in their current job for one year or less; and

4. self-employed as well as wage and salary workers who expect to work in their current job for one year or less.

In the mid-1980s, European statisticians began to address the decline of the standard employment relationship by developing the concept of precarious employment. They identified four dimensions central to establishing whether a job is precarious (Rodgers 1989: 3-5):

Degree of the situation of employed workers who face short-term work contracts or risk of termination (Rodgers 1989). It is also a key dimension of precariousness for self-employed workers (Cranford et al. 2005) whose work is mediated by commercial relationships and often involves performing services for multiple “customers,” a situation that can result in numerous short-term employment relationships (Vosko 2006).

Regulatory are both applicable to workers in need of protection and are enforceable. This dimension includes not only protection of working conditions through regulated and enforceable labour standards, but also employment benefits (statutory and social) often linked to the employment relationship such as pensions and unemployment insurance (Bernstein et al. 2006; Vosko 2006).

Control over the labour process refers to workers’ power over how work is organized and executed. This dimension is affected by membership in a union and/or coverage under a collective agreement among those in employment relationships (Jackson 2003; Anderson et al. 2006). Among self-employed workers, it is also shaped increasingly by membership in an association (e.g., professional associations; farmers’ unions).

Income Level concerns the total direct and indirect income that workers receive in exchange for the sale of their labour power. It includes wages for employees and payments received by the self-employed, government transfers, and government- and employer-sponsored benefits.

The notion of precarious employment takes analysts beyond both the narrow concept of contingent employment as temporary or transitory in nature and the broad concept of non-standard employment as those employment forms and arrangements that deviate from the full-time, full-year norm. Nevertheless, much research on precarious employment overlooks the gender of precariousness.

To remedy this shortcoming, this module draws on recent feminist scholarship that highlights the link between changing employment relationships and continuous sex/gender inequalities both inside and outside the labour market (Armstrong 1996; Bakker 1996; Fudge 1991; Spalter-Roth and Hartmann 1998; Jenson 1996; Vosko 2000). This complex set of trends may be conceptualized as the feminization of employment norms (Vosko 2002b).

The feminization of employment norms entails four key dimensions of continuity and change:

1. the “gendering of jobs”;

2. income and occupational polarization;

3. persistent occupational and industrial sex segregation; and

4. high formal labour force participation rates among women.

This module and other modules in the GWD allow for in depth examination of each of the four key dimensions of feminization.

The “gendering of jobs” is central to precarious employment. It is a process whereby certain groups of men are experiencing downward pressure on wages and conditions of work, while many women are enduring continued economic pressure (Vosko 2000, 2002a). Some scholars associate it with the presence of more “women’s work” in the market (Armstrong 1996), others conceive of it as a new set of gendered employment relations (Jenson 1996) and still others view it as involving gender transformations in the labour market (Walby 1999). Sex segregation in the occupational and industrial sector is another way of understanding the feminization of employment. Women continue to represent the majority of those employed in occupations typically defined as “women’s work” and experience positions of insecure job tenure, wage gaps and skewed employment opportunities (Vosko 2002b). Though the participation rate of women within the labour force is gradually increasing, the type of employment and the level of protection and security are questionable (Vosko 2002b).

Finally, this module allows researchers to examine the relationship between precarious employment and gender relations in the domestic sphere. The growth in precarious employment is both shaping and shaped by intensified gendered inequalities in households. Processes of economic restructuring contribute to the reconfiguration of processes linked to social reproduction. For example, the erosion of the standard employment relationship and welfare state retrenchment are leading to escalating demands of unpaid work that are falling heavily on women, particularly racialized women (Arat-Koc 1997; Bakker 1998; Cossman and Fudge 2002; Vosko 2002b) (see unpaid work module). These processes, in turn, affect relations of distribution within households or “sequences of linked actions through which people share the necessities of survival” (Acker 1988: 478).

DATA SOURCES

Several Statistics Canada surveys allow researchers to examine aspects of the relationship between changing gender relations, employment relationships and precariousness in labour markets. Each survey has strengths and weaknesses for examining precarious employment.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS), one of Statistics Canada’s longstanding surveys, produces excellent time series data on forms of employment, including temporary employment dating back to 1997. The sample size is considerable (approximately 54,000 households since January 2008), allowing for detailed analyses of precarious employment by industry and occupation.

The Survey of Work Arrangements (SWA), conducted in 1989 and 1995, is a suitable complement to the Labour Force Survey given its emphasis on employment relationships and arrangements and its useful data on benefits. A drawback to the survey is that it does not collect data on race, immigration or (dis)ability – key social locations which, like sex/gender, are related to precarious employment. Another drawback is that the survey was only conducted twice.

The General Social Survey (GSS) is an important supplement to these surveys because it collects data on temporary and other forms of employment and the social locations of race, immigration and (dis)ability. Like the Survey of Work Arrangements, the General Social Survey, Cycle 9, provides extensive data on benefits and its indicators of gender relations in households are particularly useful in the context of this module. The most recent relevant version of the General Social Survey was collected in 2006 and focuses on the challenges of family formation and early life course transitions. Data from the General Social Survey Cycle 20, address issues that are crucial for understanding the gendering of precarious employment. Factors such as family composition, child care and unpaid work, for example, are known to be linked to the higher percentage of women located in temporary and part-time employment (Vosko and Clark 2009).

The Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) is a highly innovative survey that yields an impressive data set with good data on immigration status, visible minority status and forms of employment. This survey allows for an analysis of precarious employment in the labour market and the social relations of gender, race-ethnicity and (dis)ability that surround this phenomenon.

Data are also provided in this module by two highly specialized surveys. The Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) provides data on the business strategies and organizational decisions of firms, including decisions to use temporary or contract workers. The Survey of Self-Employment (SSE) enables researchers to create a composite picture of self-employment, a form of non-standard employment that has grown dramatically in Canada and several other OECD countries since the 1980s.

Direct indicators of gender relations in households are difficult to find in quantitative surveys, particularly in the surveys that include detailed labour market variables. Though most surveys include variables about the family and household economy, we can use those measures to serve as proxies. In addition, some surveys that present good data on family class, such as the Survey of Self-Employment and the General Social Survey, include direct indicators that examine the links between household gender relations and precarious self-employment.

INDICATORS

This module allows researchers to examine the relationship between the social location of sex/gender and the following dimensions of precariousness: the employment relationship, precarious employment and gender relations in the domestic sphere, including household form and relations of distribution in households. Researchers are also able to examine how these dimensions vary by other key social locations, such as immigrant status and age, by specific work contexts, and by time and place.

Indicators of the employment relationship

Statistics Canada collects information on three indicators of the employment relationship:

1. Class of worker

2. Form of employment

3. Type of temporary employment

1. Class of Worker

Total employment is broken down by class of worker as follows:

Total Employed

a. Total Employees

i. Public Sector

ii. Private Sector

b. Total Self-Employed

i. Without Employees

ii. With Employees

c. Unpaid Family Worker

2. Form of Employment

Employees are broken down further allowing researchers to examine how precariousness varies among non-standard forms of employment and between standard and non-standard forms. Key employment forms among employees are:

Total Employees

a. Permanent employees

i. Full-time permanent

ii. Part-time permanent

b. Temporary employees

i. Full-time temporary

ii. Part-time temporary

3. Type of Temporary Employment

Temporary employment, both full-time and part-time, is broken down into three key types:

a. Term or Contract

b. Seasonal

c. Casual

Indicators of precarious employment

For Employees

This module focuses on five dimensions that researchers have identified as central to precarious employment for employees (Rodgers 1989; Fudge 1997; Vosko 2000, 2002a; Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003; Vosko 2006). They are:

a. Firm size

b. Union coverage

c. Hourly wages

d. Benefits

e. Work arrangements

For those employed, firm and establishment size are indicative of the level of regulatory protection, where small scale employers are less likely to enforce regulatory protection for its employees. The indicator of union coverage reflects precariousness, where the lack of union coverage translates into lower protection, benefits and hourly wages for employees. Benefit coverage speaks to the type and number of benefits one is entitled to; where certain benefits are only available to workers who have worked in a position for a specific duration. Benefit coverage not only depends on the length of time a worker has had a particular position of employment, but also their form of employment (part-time versus full-time employees; casual versus permanent employment, etc.) and the level of union coverage [see forms of precarious employment module of the comparative perspectives database].

For the Self-Employed

The self-employed, in contrast, are a polarized group. Own account self-employment, which is the self-employed who have no employees, is becoming more precarious (Fudge, Tucker and Vosko 2002; Vosko and Zukewich 2006). There are several indicators of precarious employment specific to the self-employed that demonstrate this trend:

a. Control over work schedule and content

b. How much work is done for one client

c. Benefits coverage and retirement preparation

d. Income

e. Adequacy of income or economic hardship

The instability of self-employment stems from the obligation to sell labour power to outside customers and clientele; the self-employed rely on their own skill set and expertise to provide goods and services and ensure economic sustainability. The level of precariousness associated with self-employment is assessed through the number of clients, amount of work performed per client and the amount of monetary compensation received for the work being performed. Though the self-employed may benefit from a flexible work environment tailored to their specific needs, they do not benefit from the same degree of regulatory protection and benefits as their employed counterparts. In addition, the self-employed experience variable income levels and income polarization (Robson 1997; Firebaugh 2003). [see forms of precarious employment module of the comparative perspectives database].

Indicators of gender relations in the domestic sphere

While it is challenging to find statistical indicators for gender relations in the domestic sphere, the module uses the best measures available, drawing mainly on the following indicators:

1. Relations of distribution in households

2. Unpaid work

3. Household form

Relations of distribution in the domestic sphere measure the level at which certain household tasks and responsibilities are divided amongst members within the household. Household form is a subsequent dimension for measuring gender relations, where the presence or absence of a spouse and/or children alters the employment, economic and domestic experience within the household. This speaks to the gendering of tasks, where certain responsibilities are labeled as “women’s work” and are expected to be performed without compensation, known as unpaid work. Women perform the majority of informal caregiving and domestic duties without monetary compensation; this contributes to the gender inequalities located inside and outside of the domestic sphere. [see temporal and spatial dynamics module of the comparative perspectives database].

1. Relations of Distribution

Employees and Self-Employed:

a. Household income

b. Government transfers

c. Home ownership

d. Class of worker of spouse

e. Occupation of spouse

Self-Employed:

a. Whether or not worker receives benefits through spouse

b. Source of supplemental income, if required

c. Percentage of household income from self-employment

d. Methods of coping with financial difficulties resulting from self-employment (e.g., government assistance, family support, sale of assets)

2. Unpaid Work

Employees and Self-Employed:

a. Number of hours per week spent doing unpaid housework (e.g., preparing meals, washing the car, doing laundry), yardwork or home maintenance for members of one’s b. own household or other households

c. Number of hours per week spent looking after one’s own children, or the children of others, without pay

d. Number of hours per week spent providing unpaid care or assistance to one or more seniors

3. Household Form

Employees and Self-Employed:

a. “Family status” (living alone, living with partner, lone parent, child living with parents)

b. Presence of children in household and their ages

c. Whether or not in a non-standard employment relationship or work arrangement due to “family responsibilities” (e.g., reason for part-time employment, self-employment, shift work, on-call work)

Indicators of social location

In the statistical tables, researchers may examine how the employment relationship, precarious employment and gender relations in the domestic sphere vary by the social locations of sex/gender, age, race, ethnicity and (dis)ability with the following indicators:

a. Visible minority status

b. Immigrant status

c. Year of arrival

d. Ethnic group

e. Aboriginal status

f. Activity limitation

Indicators of work context

Researchers are also able to examine how precarious employment varies by several key work contexts and changes therein:

a. Sector

b. Industry

c. Occupation

d. Place of work

e. Types of organizational change

f. Objectives of organizational change

g. Impacts of organizational change

Indicators of time and place

As well, researchers can examine how precarious employment has changed over time and place with the following indicators:

a. Select years between 1989 and 2009

b. Province

DEMONSTRATION 1

Using the gwd library and statistical tables

The following demonstration illustrates how the GWD allows researchers to examine precarious employment through a feminist political economy lens.

The statistical tables in the gender and work database may be used at multiple levels and for different purposes. This demonstration, therefore, assists researchers in using the numerical data in order to:

i. access estimates of the employed population in a given statistical table and represent this information visually within the database;

ii. cross-tabulate multiple indicators in order to examine a more complex research question

The library of the GWD includes a variety of sources that may be linked to data analysis. This demonstration illustrates how to use the library in order to:

i. connect a data estimate to a concept in the thesaurus;

ii. connect a data analysis to resources online; and,

iii. connect a data analysis to a search of the literature.

The first demonstration illustrates, through a step-by-step process, how to access estimates on an indicator of the employment relationship and how to graph this information.

As discussed in our section on indicators, one indicator of the employment relationship is the class of worker variable. Several tables in the database include this variable (search tables). For example, table PE LFS P-19 provides estimates using data from the Labour Force Survey.

However, this breakdown of total employment does not capture the complexity necessary to understand precariousness in Canada. There is a growing body of literature that documents different degrees of precariousness within different categories of the self-employed and employees. For example, within the self-employed, the solo self-employed are not covered by much labour law and legislation, despite the fact that many are not entrepreneurs.

The first step in the analysis is to make sure we understand what is meant by “solo self-employed”. By conducting a search on the thesaurus for the term solo self-employment, we find that it is a term for those who are self-employed and do not employ others. It is a narrower term of self-employment.

The second step in the analysis is to search the library for relevant sources. The library contains several references to papers on self-employment.

Search for a paper that examines the legal status of the solo self-employed by typing in the title, “The Legal Concept of Employment: Marginalizing Workers.” The search engine tells us that “The Legal Concept of Employment: Marginalizing Workers” is available in our library.

This paper contains a figure that summarizes scope of coverage for the solo self-employed, like independent contractors, under various pieces of labour and employment legislation (see Figure IV.1 “Scope of Coverage” in the paper). As the figure illustrates, independent contractors are not covered by employment standards or collective bargaining legislation in most Canadian jurisdictions. This suggests that researchers should be examining independent contractors, e.g. the solo self-employed, separately from self-employed employers. The statistical tables are constructed to allow one to do so.

The third step is to select (from table PE LFS P-19) the three categories of self-employment – those who employ others, those who do not employ others and unpaid family workers – and then produce a report. The results show that most self-employed do not employ others. That is, most self-employment is of the own account variety. This is true for both women and men. We also find that most unpaid family workers are women.

A fourth step is to examine how the categories of self-employment have changed over time for men and women. To examine this trend, consult tables PE LFS P-19 (1997-2005) and PE LFS P-19 2008. The data illustrates that the number of solo self-employed women has increased throughout the late 1990s, declined slightly in the early 2000s, and steadily increased since 2004.

DEMONSTRATION 2

Precarious employment and social location

As discussed above, a second indicator of the employment relationship is the forms of employment variable. A growing body of literature suggests that precariousness varies across different forms of employment. The library includes references to papers on different forms of employment, including part-time employment and temporary employment, as well as articles that link the growth in these “non-standard” forms of employment with broader trends such as privatization and economic restructuring. Also in the library is an analytic paper that supplements this conceptual guide, titled “The Gender of Precarious Employment in Canada.” This paper illustrates the need to break down total employment into mutually exclusive categories in order to determine which forms of employment are contributing to growing precariousness in the labour market.

Several tables in the database include the form of employment variable. Table PE LFS P-11 2008 provides estimates of these forms of employment using data from the Labour Force Survey.

The first step in the analysis is to examine sex by employment form.

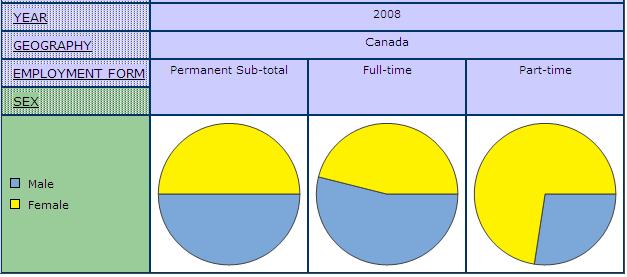

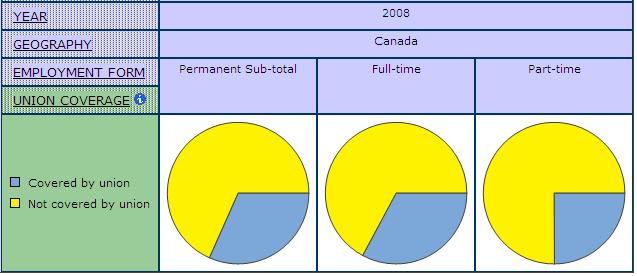

Chart 1a: Shares of Men and Women in Permanent Employment, Permanent Full-time and Permanent Part-time, Canada, 2008

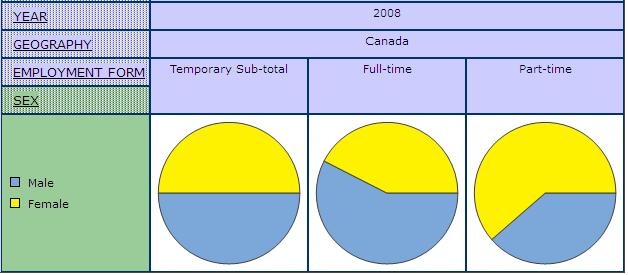

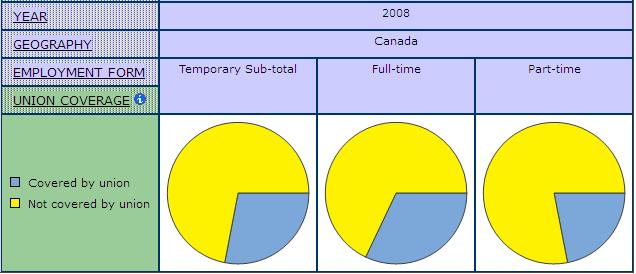

Chart 1b: Shares of Men and Women in Temporary Employment, Temporary Full-time and Temporary Part-time, Canada, 2008

Charts 1a & 1b show that permanent part-time and temporary part-time employment have larger shares of women than men, while both categories of full-time employment have larger shares of men than women.

To further our exploration of social location, we will add immigrant status. Our second step is to examine the relationship between form of employment, sex and immigrant status.

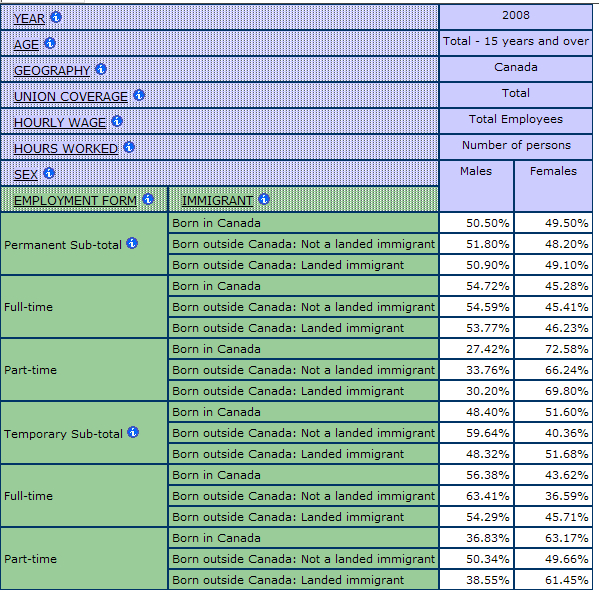

Table 1: Form of Employment by Immigrant Status and Sex, Canada, 2008

Table 1 reveals the intersection of sex and immigration status. Both Canadian-born and immigrant women are highly represented in part-time employment, where women represent at least 60% of employees in this form. Furthermore, immigrant women are highly represented, as a group, in the most precarious form of employment, that of part-time temporary employment. In general, women’s share of part-time employment, whether permanent or temporary, exceeds that of either Canadian-born or immigrant men. How precarious are the forms of employment that primarily employ women? Many analyses stop here and assume that all non-standard forms of employment are more precarious than standard forms of employment. The data in this module allows one to examine more direct indicators of precariousness, such as firm size, union coverage and hourly wage. The “Gender of Precarious Employment in Canada” (Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003) sets out a justification for including these indicators of precariousness in the statistical tables.

Accordingly, the third step is to examine an indicator of precarious employment in relation to form of employment. Here let us focus on just one indicator of precariousness: lack of union coverage.

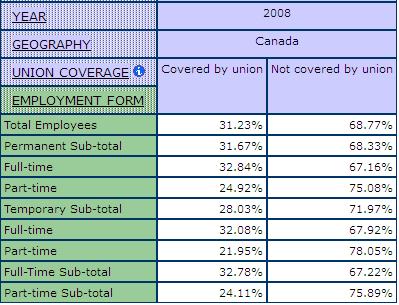

Table 2: Union Coverage by Form of Employment, Canada, 2008

Chart 2a: Union Coverage by Permanent Employment, Permanent Full-time and Permanent Part-time, Canada, 2008

Chart 2b: Union Coverage by Temporary Employment, Temporary Full-time and Temporary Part-time, Canada, 2008

Table 2 and Charts 2a & 2b show that permanent full-time employees are most likely to be covered by a union contract, followed by temporary full-time, permanent part-time and temporary part-time employees. Hence, employees are more likely to have union coverage, and the benefits of such coverage, in full-time forms of employment. However, even temporary full-time employment is less unionized than permanent full-time. Not surprisingly, the employment with the lowest union coverage is temporary part-time, revealing this category to be the most precarious in this analysis.

The library database contains references to many articles that discuss the limits of collective bargaining legislation and the resulting challenges to unionizing for temporary workers (see Yates, Michael. “Why Unions Matter“; Warskett, Rosemary. “Bank Worker-Unionization and the Law“). As well, through the library users can link to the websites of unions and other labour organizations that are working with temporary, part-time and other precarious workers to address their specific challenges in regard to collective bargaining (e.g., North American Alliance for Fair Employment, Toronto Organizing for Fair Employment, UnionNet). There are also links in the library to analytic reports from governments and various policy centers or non-governmental organizations that are also exploring this issue.

Given the GWD’s central interest in gender, after reviewing the preliminary analyses and the suggested resources above, one might ask how the relationship between form of employment and union coverage varies for women compared to men. The statistical tables are constructed to allow researchers to answer questions like this by cross-tabulating multiple indicators.

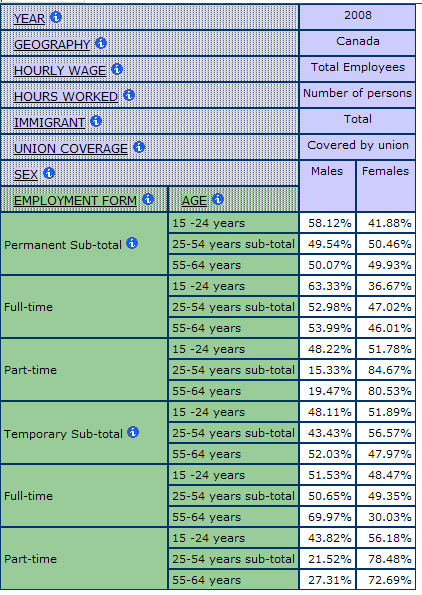

Owing to the resources mentioned earlier, we know that in conducting such an analysis, it is important to control for age, because most men in part-time and temporary jobs are young (Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003). For this next step, we will add age as the next social location to consider.

Table 3: Form of Employment by Age and Sex for Unionized Workers, Canada, 2008

The results, summarized in Table 3, show that young men between the ages of 15-24 in permanent full-time employment are more likely to be covered by a union than their female counterparts. However, owing largely to their higher relative shares of public sector employment, women in permanent full-time employment between the ages of 25-54 are more likely to be covered by a union than men. Among temporary full-time employees we observe higher rates of union coverage for women in the age categories of 15-24 and 25-54. However, union coverage among men aged 55-64 employed in temporary full-time work exceeds that of women in this age group, perhaps on account of the number of older workers who return to their formerly secure jobs on a contractual basis after early retirement. When looking at permanent part-time and temporary part-time employees, in most age groups women are more likely to be covered by a union than men. In general, this table shows that much of the difference in union coverage is related to age, where men and women in older age groups are more likely to occupy positions of employment that are covered by a union. These findings are congruent with studies linking younger workers to lower rates of unionization.

These complex trends reflect the “gendering of jobs” (Vosko 2000) – the process whereby certain groups of men, namely young men in temporary and part-time jobs, are experiencing downward pressure, such as the opportunity for union coverage, alongside many women as these precarious jobs are growing.

Furthermore, it is essential to remember the findings of our earlier analysis:

i. temporary and part-time forms of employment are less likely to be unionized (Table 2 and Charts 2a & 2b)

ii. temporary and part-time forms of employment primarily employ women (Charts 1a & 1b)

This example illustrates the need to examine trends in gender and work from multiple angles.

DEMONSTRATION 3

Precarious employment and gender relations

The final two examples demonstrate how to examine the relationship between precarious employment in labour markets and gender relations in the domestic sphere with the statistical tables and library resources.

The GWD library includes several articles on gender relations in the domestic sphere. The first step in this analysis is to search the library database for core concepts in feminist political economy related to gender relations in the domestic sphere. One core concept is social reproduction. The library also includes an analytic paper, entitled “Rethinking Feminization”, which examines the relationship between social reproduction and precariousness in depth.

It is difficult to measure concepts such as social reproduction with a single statistical indicator. However, the statistical tables include several indirect indicators of household form, relations of distribution and unpaid work. Here we demonstrate the relationship between form of employment and two of these indicators: first, household form and second, source of benefits.

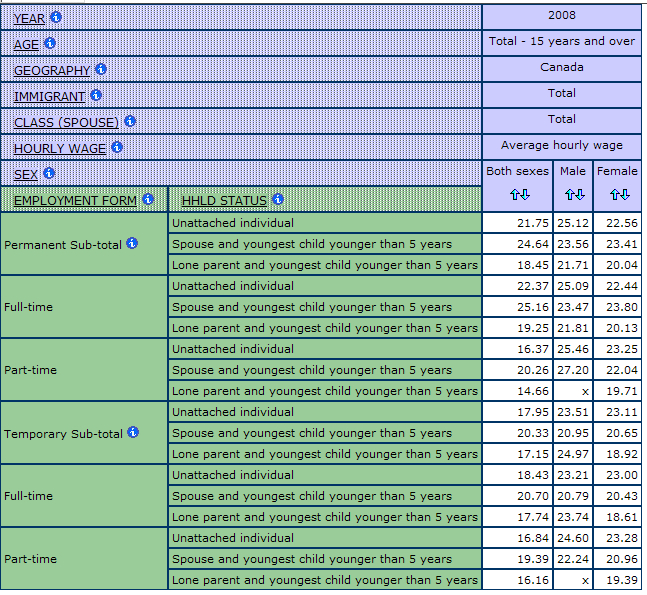

The first example examines the relationship between form of employment, hourly wages, and household form. Table PE LFS P-17 2008 provides data, from the Labour Force Survey, on hourly wages already calculated for the user and requiring no manipulation. This table also includes a variable called “household status” that combines marital status with presence and age of children. The household status variable includes many types of household form but for this demonstration we want to focus on the following three:

i. unattached individual

ii. spouse with youngest child under 5

iii. lone parent and youngest child under 5

Table 5: Form of Employment by Household Status, Sex and Average Hourly Wage, Canada, 2008

Table 5 shows a complex set of trends. For example, unattached men outearn unattached women in every form of employment. The widest gender pay gaps appear between lone parents in temporary full-time jobs (with men earning over $5 more per hour) and between permanent part-time workers with partners and young children (also $5 more per hour for men). Looking at differences among women, within each form of employment, lone mothers are doing more poorly than women with spouses. For example, permanent part-time employees who are lone parents earn much less than permanent part-time employees who are attached with children under 5. Significantly, sample sizes are too small to permit estimates for lone fathers in permanent full-time and temporary full-time jobs. In other words, there are not nearly as many lone fathers as there are lone mothers.

These findings illustrate that not only do part-time employees differ in terms of union coverage depending on if they are permanent or temporary; they also differ by household form. The examples show that men are less precarious than women across both employment and household form. Across all forms of employment, women typically earn less than men, specifically those that occupy positions of permanent part-time employment, and have a spouse with their youngest child under the age of 5. Among men and women, there is greater variance in hourly wages across permanent and temporary full-time employment, where those within temporary forms of employment earn less on an hourly basis.

The second example examines the relationship between an indicator of the employment relationship – class of worker – and an indicator of relations of distribution within households – source of benefits.

The first step is to search the more specific concept of relations of distribution in the library database. Many of the articles that came up in the search for “social reproduction” also came up in the search for “relations of distribution”. Indeed, the thesaurus tells us that these concepts are related.

The second step is to examine the data. The re-evaluation of table PE SSE E-1 from the Survey of Self-Employed, collected in 2000, provides relevant estimates of the number of self-employed by class of worker who have benefits, and the source of those benefits. The latter can be considered an indicator of relations of distribution. Added to this analysis, the source of benefits variable expands our understanding of the precariousness experienced by the own account self-employed, who were earlier shown to be the most precarious self-employed workers. Given that we also know that the unincorporated own account self employed – those whose businesses are not incorporated – are even less likely to be covered by labour laws (Fudge, Tucker and Vosko 2002), this demonstration focuses specifically on them.

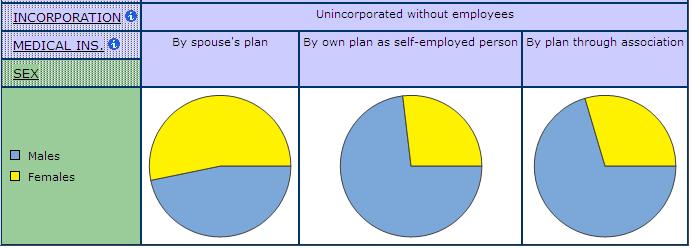

Chart 3: Source of Medical Insurance Coverage for Unincorporated Self-Employment Without Employees by Sex, Canada, 2000

Chart 3 illustrates clear gendered patterns. Women are significantly more likely than men to receive benefits from a spouse. In contrast, men are more likely to receive benefits through their own plan or through an association.

Together, these three demonstrations illustrate that by combining the GWD’s statistical tables and library resources, researchers and students will be able to address complex research questions in order to develop a more detailed account of gendered trends in precarious employment.

WORKS CITED

Acker, J. (1988). “Gender, Class and Relations of Distribution.” Signs, 13(3), 473-497.

Anderson, J., Beaton, J., and Laxer, K. (2006). “The Union Dimension: Mitigating Precarious Employment?” In Leah F. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 301-317). Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Arat-Koc, S. (1997). “Immigration Policies, Migrant Domestic Workers and the Definition of Citizenship in Canada.” In Veronica Strong-Boag and Anita Clair Fellman (Eds.), Rethinking Canada: The Promise of Women’s History, 3rd ed. (pp. 283-298). Toronto: Oxford University Press.

Armstrong, P. (1996). “The Feminization of the Labour Force: Harmonizing Down in a Global Economy.” In Isabella Bakker (Ed.), Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. (pp. 29-54). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bakker, I. (1996). “Introduction: The Gendered Foundations of Restructuring in Canada.” In Isabella Bakker (Ed.), Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. (pp. 3-28). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Bakker, I. (1998). Unpaid Work and Macroeconomics: New Discussions, New Tools for Action. Ottawa: Status of Women Canada.

Bernstein, S., Tucker, E., Lippel, K., and Vosko, L. F. (2006). “Precarious Employment and the Law’s Flaws: Identifying Regulatory Failure and Securing Effective Protection for Workers.” In Leah Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 203-220). Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Cordova, E. (1986). “From Full-Time Wage Employment to Atypical Employment: A Major Shift in the Evolution of Labour Relations?” International Labour Review, 125(6), 641-57.

Cossman, B. and Fudge, J. (2002). Privatization, the Law and the Challenge to Feminism. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Cranford, C., Vosko, L. F., and Zukewich, N. (2003). “The Gender of Precariousness in the Canadian Labour Force.” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 58(3), 454-482.

Cranford, C., Fudge, J., Tucker, E., and Vosko, L. F. (2005). Self Employed Workers Organize: Law, Policy and Unions. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

Firebaugh, G. (2003). The New Geography of Global Income Inequality. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Fudge, J. (1991). Labour Law’s Little Sister: The Employment Standards Act and the Feminization of Labour. Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Fudge, J. (1997). “Precarious Work and Families,” Working Paper, Centre for Research on Work and Society, York University.

Fudge, J. and Vosko, L. F. (2001a) “Gender, Segmentation and the Standard Employment Relationship in Canadian Labour Law and Policy.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 22(2), 271-310.

Fudge, J. and Vosko, L. F. (2001b). “By Whose Standards? Re-Regulating the Canadian Labour Market.” Economic and Industrial Democracy, 22(3), 327-356.

Fudge, Judy, Tucker, Eric and Vosko, Leah F. (2002). The Legal Concept of Employment: Marginalizing Workers. Ottawa: The Law Commission of Canada.

Fudge, J. and Vosko, L. F. (2003). “Gendered Paradoxes and the Rise of Contingent Work: Towards a Transformative Feminist Political Economy of the Labour Market.” In Wallace Clement and Leah F. Vosko (Eds.), Changing Canada: Political Economy as Transformation, Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2003, 183-213.

International Labour Organization. (1999). World Employment Report. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

Jackson, A. (2003). In Solidarity: The Union advantage. Canadian Labour Congress.

Jenson, J. (1996). “Part-time Employment and Women: A Range of Strategies.” In Isabella Bakker (Ed.), Rethinking Restructuring: Gender and Change in Canada. (pp. 92-110). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Krahn, H. (1991). “Non-Standard Work Arrangements.” Perspectives on Labour and Income, 3(4), 35-45.

Krahn, H. (1995). “Non-Standard Work on the Rise.” Perspectives on Labour and Income, 7(4), 35-42.

Muckenberger, U. (1989). “Non-standard Forms of Employment in the Federal Republic of Germany: The Role and Effectiveness of the State.” In Gerry Rodgers and Janine Rodgers (Eds.), Precarious Employment in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. (pp. 267-286). Belgium: International Institute for Labour Studies.

Polivka, A. and Stewart, J. (1996). “Contingent and Alternative Work Arrangements, Defined.” Monthly Labour Review, 119(10), 3-9.

Polivka, A. and Nardone, T. (1989). “On the Definition of ‘Contingent Work.’” Monthly Labor Review, 112(12), 9-16.

Robson, M. (1997). “The Relative Earnings from Self and Paid Employment: A Time Series Analysis for the UK.” Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 44(5), 502-518.

Rodgers, G. (1989). “Precarious Work in Western Europe: The State of the Debate.” In Gerry Rodgers and Janine Rodgers (Eds.), Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe. (pp. 1-16). Belgium: International Institute for Labour Studies.

Schellenberg, G. and Clarke, C. (1996). Temporary Employment in Canada: Profiles, Patterns and Policy Considerations. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development.

Spalter-Roth, R. and Hartmann, H. (1998). “Gauging the Consequences for Gender Relations, Pay Equity and the Public Purse.” In Kathleen Barker and Kathleen Christensen (Eds.), Contingent Work: American Employment Relations in Transition. (pp. 69-112). Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

Vallée, G. (1999). “Pluralité des Statuts de Travail et Protection des Droits de la Personne: Quel Role pour le Droit du Travail?” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 54(2), 277-312.

Vosko, L. F. (1997). “Legitimizing the Triangular Employment Relationship: Emerging International Labour Standards from a Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Labor Law and Policy Journal, 19(1), 43-78.

Vosko, L. F. (2000). Temporary Work: The Gendered Rise of a Precarious Employment Relationship. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2002a). “Gender Differentiation and the Standard/Non-Standard Employment Distinction in Canada, 1945 to the Present.” In Juteau Danielle (Ed.), Social Differentiation in Canada. Toronto and Montreal: University of Toronto Press/University of Montreal Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2002b). Rethinking Feminization: Gendered Precariousness in the Canadian Labour Market and the Crisis in Social Reproduction. 18th Annual Robarts Lecture, York University, Toronto: Robarts Centre for Canadian Studies, York University.

Vosko, L. F. (2006). Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vosko, L. F. and Zukewich, N. (2006). “Precarious by Choice? Gender and Self-employment.” In Leah F. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vosko, L. F. and Clark, L. F. (2009). “Canada: Gendered Precariousness and Social Reproduction.” Leah F. Vosko, Martha MacDonald and Iain Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment. New York: Routledge.

Walby, S. (1999). New Agendas for Women. New York: Macmillan Press.