migration

CONCEPTUAL GUIDE TO THE MIGRATION MODULE

Prepared by Valerie Preston, Leah F. Vosko and Deepa Rajkumar with past contributions from Cynthia Cranford, Christina Gabriel and Vivian Ngai

INTRODUCTION

The migration module brings together two levels of analysis. At the level of immigration policy, researchers may examine factors governing who enters Canada and under what conditions. Such policy fundamentally shapes the status and position of (im)migrants in the Canadian labour market. At the level of the labour market, researchers may focus on topics such as labour force participation, schooling, precarious employment or relations of distribution within households. Additionally, the module is designed to enable analyses of intersections of gender, race-ethnicity, and class with immigrant status, nationality and citizenship.

The literature and data in the module allow researchers to participate in the gendering of scholarship on international migration. A growing body of scholarship shows that migration policies and procedures are highly gendered and racialized (Abu-Laban 2008; Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2002; Arat-Koc 1999; Bakan and Stasiulis 1997; Benhabib and Resnik 2009; Boyd 1997; 1998; Das Gupta and Iacovetta 2000; Macklin 1995; Razack 2008; Sharma 2000; Simmons 1999; Thobani 2000). Scholarly literature also demonstrates increasing linkages between structural changes in the global economy, gender, and the incorporation of migrant women and men into different cities, sectors or industries of the host economy (Castles and Miller 2009; Gabriel 1999; Pellerin 2004; Sassen 1996; Strategic Workshop on Immigrant Women Making Place in Canadian Cities 2002; Weiner 2008), in forms of employment such as homework (Giles and Preston 1996; Ng 1999), nursing (Das Gupta 1996), janitorial work (Cranford 1998), paid domestic work (Arat-Koc 1997; Arat-Koc and Villasin 2000; Bakan and Stasiulis 1997; Bakan and Stasiulis 2005), and temporary agency work (Vosko 2000). Furthermore, there is considerable research on the earnings of migrant women and men in different types of employment, including self-employment and employment among professionals (Boyd and Thomas 2002; Ooka 2001; Shamsuddin 1998). Scholars have also examined how gender intersects with precarious citizenship statuses to shape the position of migrant women and men in the host labour force as well as the rewards garnered by them (Bauder 2008; Benhabib and Resnik 2009; Cranford 2005; Goldring 2001; Hondagneu-Sotelo 2003; Stasiulis and Bakan 2003; Vosko 2010).

Still, despite this budding literature, much research on international migration, in Canada and elsewhere, focuses on men and generalizes from their experiences. When gender is addressed, it is often considered solely within the institution of the family (Brah 1996; McIrvin Abu-Laban and Li 1998; Satzewich and Wong 2006). This enduring androcentric bias in scholarship on international migration requires an ongoing effort to write women into the literature. At the same time, simply adding women, as a variable to be compared with men, is not sufficient to gender the study of international migration (Hondagneu-Sotelo and Cranford 1998).

The migration module allows users to examine international migration as a gendered institution that shapes production and social reproduction and that is, in turn, shaped by class, gender and race-ethnicity relations. Furthermore, this module provides users with data in order to examine and create linkages between migrants’ labour market experience, households, families, education/schooling, and incorporation.

This guide is organized in six sections. The first section offers an overview of key milestones in Canadian immigration legislation and practice, including temporary foreign worker programs (TFWPs) and policies. The second section provides a conceptual overview of key concepts and analytical insights into international migration. The third section comprises an elaboration of policy categories of entry into Canada and illustrations of how immigration policy influences labour market incorporation of different groups. The fourth section deals with data sources and indicators. The fifth section offers several demonstrations using the tools of the module. The sixth and final section is a bibliography. The sections are not meant to be comprehensive but rather entry points for further study.

Immigration Policies

Under Canada’s Constitution, responsibility for immigration is shared between the Federal government and the provinces. This shared responsibility was recognized explicitly in the 1976 Immigration Act, which mandated the government to consult with the provinces (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 391).

An Immigration Act sets the broad direction and national goals of immigration policy by outlining objectives and to some extent categories of admission. Such statutes have to be approved by Parliament. Immigration regulations are the detailed rules that put the Act into practice. Such rules can be more easily changed than statutes. For example, regulations can outline the number of points an applicant needs to be considered under the skilled worker category or who exactly qualifies to be sponsored under the category “family class” (see “immigration policy categories” section).

Some of the major milestones in Canadian immigration policy, and some key gender, race-ethnicity and class markers, are outlined below.

Early Immigration Policy Directions 1867 – World War II

Early immigration policy was marked by a number of competing interests and tendencies. On the one hand, there was the attempt to use immigration policy as a mechanism of nation building in a settler society. Here, attempts were made to replicate gender, racial and class hierarchies of Great Britain, the mother country. But additionally, the demands of Canadian capital also came to the fore in the recruitment of particular groups of workers to fill shortages in the labour market. Both tendencies find expression in immigration policy (Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2002).

Following Confederation in 1867 the Canadian government made a number of attempts to attract immigrants from abroad. At this time, Chinese male workers were also actively recruited to work on the construction of the transcontinental railway. In addition, the Laurier government under the leadership of Clifford Sifton, Minister of the Interior (1896-1905), enacted aggressive measures to encourage immigrants, particularly agricultural workers, from Europe and the United States to settle in the Canadian West. At the same time, however, the Federal and Provincial governments also pursued selective admission restrictions.

The Immigration Act (1906) not only defined “an immigrant” but also barred the entry of certain groups into Canada and increased the government’s powers to deport those individuals seen as “undesirable”. It combined and streamlined existing immigration, and established an “enhanced immigration service” including Canada-US border controls, deportation measures and new regulations (Knowles 1997: 82-83).

The Immigration Act (1910) subsequently gave the Federal government powers to exclude “any nationality or race of immigrants of any specified class or occupation, by reason of any economic, industrial, or other conditions temporarily existing in Canada or because such immigrants are deemed unsuitable having regard to the climatic, industrial, social, educational, labour [conditions]… or because such immigrants are deemed undesirable owing to their peculiar customs, habits, modes of life…and because of their probable inability to become readily assimilated…” (cited by Jakubowski 1997:15-16). During this period, legislation included explicit discriminatory racial criteria. Within legislation and regulations gender, race-ethnicity, class and nationality intersected to control the terms of entry and (lack of) settlement for different groups.

Specific provisions barred the entry of certain groups. As early as 1885, policies were enacted to actively discourage Chinese immigration through the imposition of a $50 head tax. This was subsequently raised to $100 and then to $500 in 1903 (Knowles 1997: 51). It was not until June 2006, under much public pressure, that the government apologized for this head tax. Similarly, through an amendment to the Immigration Act (1908) South Asians were subject to the requirement of “continuous journey” stipulation, which required immigrants to migrate directly to Canada, without stopping en route, or else they were barred entry. As well, South Asian women were banned from entering Canada. In 1919 this rule was relaxed to allow South Asian wives to immigrate (Das Gupta 1995: 154).

The Immigration Act (1952)

Throughout the immediate postwar period a system of national preferences for migrants was still in place. Mackenzie King’s government defended its right to deploy discriminatory entry criteria. Thus preference was given to applicants from “old Commonwealth” countries and the United States. His administration also moved to accept thousands of displaced Europeans to enter Canada (Knowles 1997: 131-132).

In 1950, the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC) was established. Agreements were also signed with the governments of India, Pakistan, and Ceylon in 1951. Under a system of quotas, Canada agreed to accept small numbers of their citizens as immigrants (Knowles 1997: 137). For example, the 1951 quota was to accept 150 Indians, 100 Pakistanis and 50 Sri Lankans per year. These quotas remained in place till 1967 (Das Gupta 1994: 61-62).

A new Immigration Act was introduced in 1952. Much of the Act was concerned with detailing the categories of people who should not enter Canada, “by reason such as nationality, ethnic group, occupation, lifestyle, unsuitability with regard to Canada’s climate”. It also included measures for controlling entry of those who had no legal right to enter, and/or who were cast as “undesirable”. Additionally, the Act gave the Citizenship and Immigration Minister and officials wide-ranging discretionary power (Knowles 1997: 138).

1962 Immigration Regulations

The 1962 regulations signaled a major turning point in Canadian immigration policy. At this time the government sought to increase the number of skilled workers while simultaneously reducing the number of unskilled workers entering Canada. More importantly, for the first time, race and country of origin were not stated factors in immigration selection. The regulations did not indicate a preference for particular countries but instead emphasized that selection should be based on “education, training, skills or other special qualifications” indicating that the applicant will “likely be able to establish himself successfully in Canada”, and has “either sufficient means to support himself or has secured employment”. Nevertheless, immigration officials still retained considerable discretion in determining which skills were important (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 332).

The government, at this time, also moved to liberalize sponsorship provisions but it proceeded along a two-tier basis. A Canadian could sponsor parents, grandparents, spouse, or children under the age of twenty-one. However, a qualification was introduced – only Canadians from preferred nations could “sponsor children over twenty-one, married children, siblings and their corresponding families and unmarried orphaned nieces and nephews under the age of twenty-one” (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 333). In other words, the latter group could sponsor a wider range of people. This measure was designed to address concerns that there would be a large number of unskilled relatives sponsored from India. This clause remained in place until 1967 (Knowles 1997: 152).

1967 Immigration Regulations

The 1967 regulatory changes had a major impact on the composition of Canadian immigration (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 351). The 1967 regulations created a new selection model called the “points system”. It has been pointed out that the introduction of the system was important on two levels – procedurally and substantively (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 352). In terms of process this model limited administrative discretion, which was a hallmark of the previous selection system. That is, whereas in the past an immigration official determined whether an independent applicant was suitable on the basis of personality, work experience and education under the new model the immigration officer awarded points, up to a maximum, in nine areas. These areas included education, employment prospects in Canada, age, personal characteristics, official language ability. Applicants had to earn 50 points to pass (Knowles 1997: 158); presently, applicants must earn a minimum of 67 points. Additionally, on a substantive level, this new system undermined the elements of overt discrimination that remained in the old selection model (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 351).

The emphasis on skill and education still had race-ethnicity, class and gender implications insofar as people from certain social groups in countries abroad do not have the same chance to obtain these criteria. For example, the emphasis on education and work favors people who can obtain and/or pay for appropriate formally recognized training (Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2002: 48). Similarly, the focus on particular skills can adversely impact women insofar as much of what is considered “women’s work” – caring, cleaning, teaching – is undervalued. The selection model also did not award points for unpaid work (Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2002: 50-51). Thus, the adoption of a points based model did not necessarily change the arrival status of most women. Some women qualified under labour recruitment criteria, but most women entered as dependents (Boyd 1986: 46). Furthermore, in the case of male-female households, only the characteristics of the male adult were used as the basis for admission even in those cases where a wife could score more points. As Boyd points out, “this practice simply reflected the assumption that men, not women, were heads of households.” This was subsequently changed in 1974 when regulations allowed women to be a “designated person in a household” upon whom the points based system would also apply (Boyd 1986: 46). Additionally, the selection system was not the only factor that determined which people would come to Canada. The location of overseas offices and staffing levels played a significant role in determining the composition and flows of immigrants. In the 1960s, the ports of entry in the US, Britain, and Western Europe were well staffed in relation to volume of applicants. The same did not hold true for Southern Europe and other parts of the world (Knowles 1997: 159).

The other important change in the regulations was the elimination of remaining discriminatory provisions in relation to sponsorship rights. The new regulations eliminated different provisions between Canadian citizens and landed immigrants, but also limited the range of relatives eligible for sponsorship (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 352). Sponsorship programs, however, have been characterized as a “double-edged sword” (Boyd 1986: 46). On the one hand, they allow the entry of those who may not have qualified under the points-based selection model. On the other hand, sponsorship programs can reinforce dependency and unequal power relations within the household (Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2002; Arat-Koc 1999; Arat-Koc and Villasin 2000; Boyd 1986; Langevin and Belleau 2000; NAWL 1999; Ruhs and Martin 2008). The family class immigrant’s status is intimately tied to the sponsor’s continuing support. This renders a family class immigrant very vulnerable in situations of unsatisfactory family relationships (Arat-Koc 1999: 39). Initially, as well, the status of a sponsored individual was contingent on the status of the sponsor. Women, for example, were vulnerable to deportation if their sponsors were deported (Boyd 1986: 47). Furthermore, those who are sponsored may also find that their eligibility for publicly provided language and skills upgrading services are affected.

Immigration Act (1976) and 1978 Regulations

In many ways the 1976 Immigration Act and its subsequent regulations laid the foundation for current immigration policy and practice. Unlike previous Acts, the 1976 legislation sets out the principles and objectives of Canadian immigration policy. These included attainment of Canada’s demographic goals, promoting family reunion, upholding Canada’s humanitarian tradition by welcoming refugees, and fostering the development of a strong economy (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998: 390).

The Act also recognized that immigration is a concurrent power and required the Federal Government to consult with provinces as well as relevant stakeholders. Subsequently, the Federal government signed agreements with individual provinces to manage and coordinate immigration. The Canada-Quebec Accord (1991) is the most comprehensive of these agreements. Under its terms, Quebec has sole responsibility to select all independent immigrants (now called “skilled workers”; see “immigration policy categories” section) and refugees who wish to settle in the province.

Moreover, the Act required that the Federal government plan future immigration levels. As a result, each year the Federal government tables an Annual Report to Parliament on immigration levels.

Furthermore, immigration categories were explicitly outlined through the provisions of the 1976 Act. Each category was governed by a different set of selection criteria. The categories were as follows:

Independent class (now called “skilled workers and professionals” class; see “immigration policy categories” section): This category consisted of those applicants who were immigrating to Canada on the basis of their individual attributes. The points model was used as the selection system. In cases where the individual was married, s/he was designated the “principal applicant” and family members (spouse and dependent children – if any) entered as accompanying spouses and dependents or under the provisions of the family class. In other words, the points system was not applied to accompanying spouses and children.

Family class: People in this category are sponsored; they are exempt from points-based criteria but must pass security and medical screening. Under this provision, a sponsor in Canada had to demonstrate sufficient means to care for an individual for a period of ten years. Family class included spouses, fiancé(e); unmarried children under twenty-one; aged (over sixty) or disabled parents; orphaned sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews (Kelley and Trebilcock 1998).

Humanitarian class: For the first time the 1976 Act recognized the category of refugee as distinct from other categories of entry. Prior to the designation of this category, refugee determination was ad hoc or determined by the executive. The Act listed the grounds upon which a refugee could settle in Canada (see “immigration policy categories” section). It also established the Refugee Status Advisory Committee whose purpose was to make refugee determination for those individuals making claims within Canada and to safeguard against their arbitrary deportation (Knowles 1997: 170).

Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) 2002

The Immigration Act (1976) was amended numerous times, throughout the 1980s and 1990s. In the early 1990s, Jean Chretien’s Liberal government began a fundamental overhaul of Canada’s immigration policies. There was an attempt to change the composition of immigration intake away from the family class and towards independent applicants who are selected under the points system (i.e. “skilled” workers). Additionally, the administration introduced new cost recovery measures. In 1995 the government introduced the Right of Landing Fee (ROLF) (now the Right of Permanent Residence Fee or RPRF). This fee, which is often referred to as a head tax, required all adult immigrants to pay $975 dollars upon entry to Canada. This fee was in addition to other processing fees. In 2000, CIC eliminated the RPRF for those entering Canada under humanitarian grounds, such as government assisted refugees. In 2006, the RPRF was cut by almost half for all other immigrants. It nevertheless continues to act as a barrier for many immigrants. Furthermore, there are gendered implications insofar as the RPRF disproportionately affects some disadvantaged groups. For instance, those immigrants who are applying to enter Canada through the family class or Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP) still need to pay the RPRF; these immigrants tend to be women who often earn very low incomes.

In 2000, the Federal Government introduced the first new Immigration Act since 1976. The IRPA was proclaimed into law in 2001 and was implemented in 2002. Under its provisions, the points-based selection model is retained for skilled principal applicants (i.e. those who are not refugees), and assessment is determined on the basis of education, official language ability, work experience, age and arranged employment in Canada. The emphasis is on selecting individuals with transferable skills as opposed to specific occupational criteria.

Since 9/11, the IRPA has been amended in order to securitize Canada’s borders and immigration (see “securitization” in key concepts). On December 29, 2004, for instance, Canada and the United States implemented the Safe Third Country Agreement (signed on December 5, 2002). The Agreement requires refugee claimants to seek asylum in the first safe country in which they land, and both Canada and the United States are considered safe countries in the Agreement. As a result, refugee claimants can no longer apply for protection at the US-Canada border. Refugee advocates assert that the United States is not a safe country for all refugee claimants. Additionally, the Agreement has the effect of increasing interdiction efforts and adding one more barrier to refugee claimants seeking protection; so much so that some have called the safe third countries silent killers in closing off its borders to asylum seekers, especially women, and contributing to their vulnerability. This provision only increases smuggling and irregular crossings at the border (Canadian Council for Refugees 2005). For instance, before the Agreement, Canada accepted 81% of Columbian refugee claimants, whereas the United States accepted a mere 45%. Since 2005 the number of Columbian refugee applicants in Canada dropped significantly, from being a group that made the largest number of claims in 2004. Consequently, there are a large number of Columbian refugees who live in fear of detention or deportation within the United States (Canadian Council for Refugees 2005).

In the post 9/11 period, immigration to Canada has been managed primarily at the federal level. However, nearly every province has entered into Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) agreements with CIC in order to gain more control over immigration. Depending on each specific agreement, employers, communities, families or the migrant workers themselves can apply for work permits or permanent residency for migration. With a few exceptions, most PNPs are employer-driven, meaning that employers or investors have more control over which migrant workers or students they want to hire. This shift from federal to provincial control over migration, along with greater non-government influence over selection, is indicative of increased regionalization. And, because PNPs are mostly employer-driven, it transfers government power and immigration control to individual employers. Different provinces’ needs for various levels of skilled workers, moreover, introduce a geopolitical dimension to discussions surrounding immigration policy and the labour market.

Consistent with this tendency, in September 2008, CIC created the Canadian Experience Class, a new category for immigration. The CEC allows for certain individuals who have temporary status to apply for permanent status after 2 years of working or learning in Canada. Only international students or “high-skilled” temporary migrant workers are eligible to apply.

The new PNPs and CEC are primarily geared towards permanent economic immigrants. While PNPs have become integral to Canada’s migration policies the federal government has also increased the number of, and its reliance on, the TFWP. The TFWP allows for employers to recruit and hire migrant workers to fill labour shortages. Under the TFWP, employers can hire workers with various (i.e., “high” or “low”) skill levels, although the program is geared towards low-skilled workers. Two longstanding, and relatively autonomous, programs under the TFWP are the LCP and the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Program (SAWP). Presently, most workers under the TWFP are ineligible for permanent status after their contract has expired – the only exceptions are LCP and high-skilled workers. Most low-skilled workers remain in precarious and temporary working conditions; and they have limited options, or none at all, for family reunification in Canada.

In February 2007, the Canadian government initiated the Low-Skilled Pilot Project for temporary migrant worker programs. The pilot has two main objectives: to increase a temporary migrant worker’s maximum duration in Canada from 12 to 24 months, and to allow temporary migrant workers to stay in Canada if their contract is renewed. Previously, temporary workers were not allowed to stay in Canada once their contract expired. While this pilot project is an improvement on the TFWP, it serves to maintain the precarious status and employment situations of some migrant workers – low-skilled temporary workers are still ineligible for permanent citizenship status, but can remain in Canada for an indefinite amount of time. Furthermore, SAWP workers are ineligible under the pilot project, and thus are still required to return to the countries where they came from between contracts.

Pilot projects, such as the Low-Skilled Pilot Project for temporary migrant worker programs, often lay the groundwork for more permanent shifts in policy, away from permanent immigration towards temporary migration; many TFWPs have emerged from pilot projects. The Low-Skilled Pilot Project is indicative of Canada’s shift towards more conservative immigration policies. These regulations, while increasing migration under the TFWPs are simultaneously creating more barriers for permanent immigration. This has the effect of increased precariousness in employment for temporary migrants as they lack access to social benefits, such as employment insurance, as a result of their migrant status.

In June 2008, the Canadian government introduced significant amendments to IRPA buried in Bill C-50: Budget Implementation Act. The amendments give the Immigration Minister arbitrary power to decide on immigration applications and to set or modify criteria for entry into Canada. The stated purpose of the amendments is to expedite the immigration process and reduce the backlog of applicants. However, it fundamentally changes the immigration system, away from the points-based system, insofar as it gives the Minister much greater authority over decisions on who can and cannot enter Canada, and under what conditions. The system is now geared to expedite immigration applications, both permanent and temporary, for skilled and low-skilled workers who will contribute immediately to Canadian economy.

With this overview of key milestones in Canadian immigration legislation, the discussion turns now to review key concepts guiding the module’s organization.

KEY CONCEPTS

This module is organized around a number of overarching concepts central to both policy and labour market analyses. It begins with the assumption that policy categories shape one’s position in the labour market. This section outlines the different concepts used in the module and points researchers to definitions and semantic relationships in the thesaurus.

Global Restructuring

The concept of global restructuring is well suited to bring an analysis of international migration into our study of gender and work. Restructuring denotes the economic, political and social changes in many countries and world regions in response to globalization (Neysmith 1999). The term “global restructuring” emphasizes that these processes of change are occurring in multiple locations and are linked to one another. Migration, one aspect of globalization, articulates with other aspects of globalization, such as structural adjustment policies and foreign direct investment. States also respond to labour mobility. State responses are highly visible in immigration policy, making it useful for researchers to track the implications of migration for work, both temporary and permanent, through data on a national economy. From a critical perspective, the questions become: which workers are permitted full mobility across borders and which workers are not? Under what conditions can (and do) people enter Canada? How does their entry influence their position in the labour market?

Racialization

Conceiving of migration as a central aspect of global restructuring pushes one to consider how changes in the economy may intensify racialization. Racialization refers to a process of signification in which people are categorized into “races” by reference to real or imagined phenotypic or genetic differences (Miles 1987: 7; Satzewich 1991: 5). Racialized identity categories, such as “visible minority”, “Black”, “South Asian”, “White”, as well as a post-9/11 conception of “terrorist”, are constructed through processes of racialization embedded in daily interactions, ideologies, policies, and practices. These categories are highly contested (Miles 1987; Razack 2008). At the same time, the significance of identities for resistance and agency underscores the importance of retaining terms such as “Black” and “people of colour” (Dua 1999; Das Gupta 2002; Galabuzzi 2004; Mensah 2002; Mohanty 2003). Racialization is analytically distinct from “racism”, which is an ideology that ascribes negatively evaluated characteristics in a deterministic manner to a group that is also identified as being in some way biologically distinct. However, the two processes are historically intertwined; these linkages are evident in policies and practices regulating different types of migration. Often, racialization aligns with racism when it is bureaucratized and used as a political tool (Razack 2008).

The Canadian government’s LCP, for example, is sometimes referred to as “trafficking of women”, specifically women migrant workers from the Philippines, insofar as it systematizes the recruitment and entrapment of Filipino women into highly precarious working environments (Langevin and Belleau 2000). While the policy itself appears to be neutral in terms of race and gender, the vast majority of the program’s applicants are female and Filipino.

As well, before 9/11, the Canadian government did not have an official legal definition of terrorist or terrorism. In December of 2001, it passed the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) in which terrorist activity is defined as “in whole or in part for a political, religious or ideological purpose, objective or cause, and…in whole or in part with the intention of intimidating the public, or a segment of the public”, among other prepositions (Anti-Terrorism Act 2001). Similar to the LCP, the policy itself is neutral in terms of race and gender; however, its practical implications almost always involve Muslim-passing men (Abu-Laban 2002; Razack 2008).

International Migration

This module uses the term “international migration” to refer to the process of movement and incorporation into host societies. Many studies of the incorporation of people into host societies use the term “immigration”, but this term places undue emphasis on permanent settlement in the host country.

Traditionally, the dominant perspective in immigration studies was the assimilation paradigm, which assumed that immigrants would settle permanently in the host country and become similar, culturally as well as socio-economically, to the native-born population. However, not all studies of “immigration” accept the idea of assimilation. As Castles and Miller (2009) note, there are several predominant theories for explaining international migration: neoclassical theory, new economics theory of labour migration, dual (or segmented) labour market theory, world systems theory, and transnational theory. Neoclassical theory, an outdated and heavily criticized approach, focuses on so-called “push” and “pull” factors of migration for individuals such as low wages or high labour demand respectively (Hirschman, Kasinitz, and DeWind 1999; Castles and Miller 2009). The new economics theory of labour migration is an extension of the neoclassical theory insofar as it addresses similar migration factors, but for families and social groups rather than individuals (Stark and Bloom 1985; Castles and Miller 2009). Dual labour market theory, while it is mainly an economics-based approach, focuses on a wide range of migration factors such as the roles of government, employers, race, and gender as well as demand for high and low skilled-workers. This approach, too, is outdated, and most of its proponents, such as P.B. Doeringer and M.J. Piore, wrote mainly in the 1970’s and 80’s. World systems theorists, such as Immanuel Wallerstein, shift away from an economics-based approach and analyze migration patterns by focusing on movement between “core” capitalist countries and less-developed “peripheral” regions (Castles and Miller 2009). Lastly, transnational theorists such as Schiller, Portes and Sassen tend to focus on human agency or global networks, whereby people are understood to migrate due to social, cultural, and economic linkages (Castles and Miler 2009).

Transnationalism

Transnationalism refers to the linkages and interactions between people and/or institutions across nation-state borders. Over the past 20 years, globalization, along with technological advances in communication and transportation, has increased linkages between individuals, communities, and institutions across the world. Transnational practices, similarly, are those that are not bound by borders. These can include dual citizenship, voting in the elections of the multiple countries in which people have citizenship (only where it is allowed), or financially supporting families or organizations rooted in the country which migrants were previously from. Furthermore, the concept of transnationalism can be applied and understood in various ways: as a means to channel capital, as a type of consciousness or identity, or as a space for political engagement (Basch, Glick-Schiller and Blanc 1994; Cohen 1997; Castles and Miller 2009; Mitchell 2001a; Kobayashi and Preston 2007; Satzewich and Wong 2006).

An example of transnational or global social policy practices that are not necessarily bound by nation-nation relations is the unprecedented agreement, between a union, the United Food Commercial Workers Canada (UFCW), and the Mexican state of Michoacán signed on 24 February 2009. Significantly, its participants and signatories include government officials, workers’ organizations, and civil society groups. The agreement is meant to enhance (temporary) migrant worker protections, and advocate for human and labour rights of Michoacán agricultural workers. In particular, as per the agreement, support centres run by the Agricultural Workers Alliance (AWA) advocate on behalf of workers, provide them counseling on housing, labour rights, medical claims and other labour issues as well as conduct workshops on health and safety, and workers compensation (WSIB) claims. The centres also offer English and French language classes, and provide free long distance telephone access – which is indicative of its unique transnational character that help retain community ties in their home as well as host societies.

Diaspora

The concept of diaspora, in conjunction with transnationalism, alerts one to the possibility that even those who come to settle in host societies remain connected with “home” communities (Cohen 1997; Basch, Glick-Schiller and Blanc 1994; Portes, Guarnizo and Landolt 1999), and may eventually relocate to another country. Definitions and understandings of diaspora and diasporic subjects vary greatly. From the 2nd Century CE until 1968, “diaspora” had a Jewish-centred connotation, which necessarily contained the following elements: facing coercion which leads to resettlement, a clearly delimited identification to a homeland, having collective memories which shape identities, communication and contact with people in the homeland, and some form of desire to return to the homeland. In the late 1960’s, the meaning of diaspora shifted from this Jewish-centred definition due to expanding analyses on multiculturalism and literary and cultural theory. One contemporary definition, put forth by Walter Conner, is that a diaspora is “that segment of people living outside the homeland” (Tölölyan 1996). To Conner and others, there is a substantial subjective component to diasporas – diasporic subjects must identify and represent themselves as such.

Contemporary notions of diaspora tend to centre on the homeland – either diasporic subjects maintain connections with the homeland, or they might one day return home. However, these understandings of the homeland and feelings of homeliness can be problematic (Sharma 2005). For example, some conventional diaspora discourses can be marked by a backward-looking gaze, where diasporic subjects are nostalgic for their “lost origins” and of times past. The longing for “times past” as well as the primacy of displacement often reifies problematic notions of the “home” nation – that it is a singular, coherent and cohesive national community. By reducing diasporic subjects’ experiences to a nostalgia for “back home”, people assume fixed and unchanging national cultures, traditions, populations, and relationships. The nostalgic longing for a “back home” also presupposes some common ancestral homeland in which all diaspora members within a community share; this again reifies the problematic of unified, cohesive, and stagnant national traditions and cultures that every diasporic subject should know and share.

Some gendered notions of diaspora and homeland can also be essentialist. For example, dominant diasporic narratives often position women as the space of the home, in which they preserve diasporic identities and traditions. Women are often perceived as the vessels for producing and maintaining the “pure” and “authentic” cultures and traditions from “back home” as well as in the home. The female body is fixed to the perceived origins of one’s diasporic identity – the home and nation that was left behind – in order to maintain and (re)produce a sense of community belonging and identity. The female body, then, is something that is acted upon, as opposed to being seen as agential subjects within the diaspora – they become reduced to their alleged use-value, which is to maintain the “pure” cultures and traditions from their perceived origin: “back home” (Brah 1996; Castles and Miller 2009; Fortier 2002; Mitchell 2001b; Satzewich and Wong 2006; Tölölyan 1996).

Securitization

In host societies as well, certain conceptions of “home”, and their associated inclusions and exclusions, are upheld and embedded, even within government policies. One lens for examining these inclusions and exclusions is securitization – or processes of increasing (typically national or place-based) “security” common in the five related policy fields: industry; employment and labour; environment; immigration; and, activities of the military. Securitization is thus a lens through which to probe why and how certain objects, people, or places are scrutinized and fixed or mobile in place and space (Buzan, Waever and Wilde 1998).

The attacks on the World Trade Centre in September 2001 mark a drastic turn in international migration scholarship and policies towards an increased stress on security. In the context of international migration, securitization encompasses measures related to both state security and human (in)security (Castles and Miller 2009). On the one hand, state security, in a post-9/11 context, has affected international migration insofar as it restricts the number of immigrants and migrants accepted, for example, in Canada by CIC. Furthermore, international migration is largely driven by human (in)securities. Those who are living in countries where they are affected by violence or lack certain rights are more likely to migrate to a country in which they feel more secure. On the other hand, some migrants face certain challenges in host societies in so far as they are perceived to be security threats to the receiving country. Insecurity is usually due to a combination of cultural, socioeconomic, and political factors (Castles and Miller 2009).

An important site to be examined in the context of securitization and international migration is the nation-state border. Although globalization has increased the porosity of borders in certain ways, there has also been a shift to enforcing and strengthening them especially in a post-9/11 context. Specifically, goods and services are able to flow across borders more freely with lesser taxation, but migration can be much more controlled, restricted, or policed. Much more so than before 9/11, trade and migration issues are now discussed through a securitization lens which focuses on controlling and securing borders (Abu-Laban and Gabriel 2003; Adelman 2002; Andreas 2003; Arat-Koc 2005; Gabriel and Pellerin 2008; Pratt 2005).

Increased securitization in Canada restricts immigrants from permanently residing in Canada and gaining citizenship. Since 9/11, the Canadian government has passed numerous Acts and policies which further securitized their immigration policies and border controls. For example, the ATA, passed in December 2001, defines terrorism and terrorist for the first time in official policy; it amends the criminal code and the IRPA in order to “deter and disable terrorist organizations”. Around the same time the ATA was passed, so too was the Smart Border Declaration, which was an agreement with the United States to enhance security, specifically to securitize the border.

Another area where securitization has intensified is with regard to human smuggling and trafficking. In May 2002, Canada signed the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNCTOC) which addresses human trafficking. And in November 2005, the federal government passed Bill C-49: an Act to amend the Criminal Code (trafficking in persons), which attempts to address both domestic and international trafficking. While this is a concern about trafficking, inherent within anti-trafficking campaigns is often a neglect of the possibility of migrants’ agency to migrate without official permission. Furthermore, anti-trafficking campaigns lead to racialized criminalization of those assumed to be the traffickers while restricting certain immigration practices that are self-willed (Sharma 2003; Kempadoo 2005).

Citizenship

This module does not assume that the entry into Canada is permanent, voluntary, or legal (i.e., pursued through channels specified in immigration policies). It also proceeds on the basis that it is important to distinguish between those who have been given various statuses by the Canadian state and those who have no recognized status at all. Conceiving of international migration as a process allows for an analysis of different formal and informal citizenship statuses and their implications. While formal citizenship denotes political and civil rights within the bounds of a nation-state, informal citizenship refers to membership in a particular group, workplace or community on the basis of one’s social and political participation. Informal citizenship is sometimes used to refer to non-status migrants while recognizing them as active social and political actors. But the term can also encompass those who might be formal citizens in one country yet participate in transnational communities, in which case they can be referred to as transnational citizens (Abu-Laban 2005; Sassen 2006). Informal citizenship, therefore, is not necessarily bound by a nation-state’s legal, geographical, and political constraints.

Recently, the migration of people across borders without the sanction of the state they are entering has garnered significant attention in policy circles and scholarly literature concerned with migration to high-income countries (Hondagneu-Sotelo 2003; Khandor et al. 2004; Kang 1996; Koser 2001; Orrenius and Zavodny 2003) – even as there is not much official statistical data on migrants with undocumented or even temporary statuses. These migrants may reside in countries for many years without legally sanctioned residency. Their lack of legally sanctioned rights, or formal citizenship, does not mean that they do not engage in social or economic practices of citizenship or informal citizenship (Cranford 2007; Goldring 2001; McNevin 2009). But, their precarious legal status does shape significantly their position in the labour market (Cranford 2005; Hondagneu-Sotelo 2003). In conservative political and popular discourse, those lacking formal citizenship are often referred to as “illegals” (in the U.S.A) and “asylum seekers” (in Europe). In liberal and left scholarship and discourse they are called “undocumented”, or “irregular” migrants or simply those “without papers” or “without status”.

In July 2003, the UN International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW) entered into force. The ICMW distinguishes between “regular” and “irregular” migrants: regular migrants are authorized to enter the country, whereas irregular migrants are unauthorized or undocumented. Acknowledgement of this distinction by the ICRMW is significant as it provides for UN sanctioned basic human rights to all migrant workers, regular and irregular. Canada, however, has not ratified this convention for the official reason that a majority of those classified as migrants still enter Canada as permanent citizens to whom these rights are ensured. Thus, the Federal government has not deemed it necessary to actively provide for the extension of rights to temporary and undocumented migrant workers, who do not have permanent resident status, such as the right to educational, housing and unemployment benefits, arguing that these migrant workers’ human rights are protected under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and other international conventions that Canada has ratified (Piché, Pelletier and Epale 2006). An additional objection is that the ICRMW carries in it extra-territorial obligations that Canada does not agree with. Furthermore, ratifying the ICRMW would require that Canada review’s its temporary migrants programs (Piché, Pelletier and Epale 2006).

In Canada, the term “non-status migrant” is the most widely accepted term used to denote people who do not have a recognized or regulated citizenship status in the country of their residence, and we use that term in this module. In Canada, non-status migrants range from people whose temporary work visas have expired, people arriving on visitor or student visas and staying to work without permit, people who entered as refugee claimants but did not receive permanent status and stayed, and people who crossed the border clandestinely. The non-status population is not categorized as such in official statistics.

Non-status people in Canada have very limited opportunities to regularize their immigration status, although there have recently been calls for regularization programs that would allow non-status immigrants to apply for official legal status. Currently, the only official option for obtaining status is through a Humanitarian and Compassionate (H&C) application (Khandor 2004; Standing Committee 2009). However, there are numerous issues and barriers in using H&C grounds for obtaining status, such as exceedingly slow processing, processing fees and inconsistent case precedent and decision-making (Canadian Council for Refugees 2006).

Citizenship can mean inclusion and universalism as well as exclusion. Bosniak (2006) examined this contradiction, inherent in the practices and institutions of citizenship in liberal democratic societies, by analyzing alienage and alienage law and its complexities. The contradiction is dramatic for those labeled as aliens, transnational migrants without full citizenship status, in the context of highly porous borders and increasing transmigration where the meaning of citizenship is changing. Alienage, as a specific form of non-citizenship, is a useful lens to examine the meaning of citizenship, its promises and limits. It also allows users to analyze how processes of globalization shape legal and social relationships and structures within national societies.

Multiculturalism

Similar to citizenship practices and policies, multiculturalism is an important site for researching international migration and settlement practices and policies in Canada. Multiculturalism in Canada can be understood through several lenses: descriptively, prescriptively (as ideology), from a political or policy-based perspective, or as a social and cultural process resulting from transnationalism and globalization (Dewing and Leman 2006; Satzewich and Wong 2006).

In the face of globalization and increasing transnational linkages, multiculturalism extends beyond mere government policy and can also be perceived as a social and cultural phenomenon. For instance, many Canadians feel as though multiculturalism is a large part of their national identity and “culture” which distinguishes them from other countries such as the U.S. (Dewing and Leman 2006; Satzewich and Wong 2006). In other words, it is a social and cultural ideal held by many groups within Canada in order to respect and tolerate racial and cultural diversity which is directly linked to international migration.

In its most literal sense, multiculturalism is a descriptor of Canadian society – there are many different cultural and racial(ized) groups and communities within Canada. In an ideological context multiculturalism can be perceived as a set of ideals regarding the “celebration of Canada’s diversity” (Dewing and Leman 2006). On the level of policy, the Canadian government has attempted to institutionalize multiculturalism, otherwise known as Official Multiculturalism.

There are roughly three phases of federal multiculturalism: incipient (pre-1971), formative (1971-1981), and institutionalization (1982 to the present) (Dewing and Leman 2006). In the incipient phase, cultural diversity was increasingly more accepted within society, but not formalized through policy. Canadian policy was still centered on an assimilation paradigm. In the formative years, Canadian policies shifted from a paradigm of assimilation to one of integration. In 1969, specifically, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism published a report, which recommended the integration of migrants and non-European settlers (McRoberts 2004). Some of the report’s key objectives were: to assist cultural groups to retain and foster their identity, to assist cultural groups to overcome barriers to their full participation in Canadian society, to promote creative exchanges among all Canadian cultural groups, and to assist immigrants in acquiring at least one of the official languages (Dewing and Leman 2006). In 1973, the Canadian government created a Ministry of Multiculturalism in order to implement some of the report’s key objectives (McRoberts 2004). In the institutionalization phase, multiculturalism was introduced and formalized in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982. Specifically, section 27 states “this Charter shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians” (Dewing and Leman 2006). In 1987, a House of Commons Standing Committee on Multiculturalism suggested that the federal government create a policy on multiculturalism. The following year, the federal government passed the Canadian Multiculturalism Act (1988), which created a Department of Multiculturalism, and formally codified Official Multiculturalism allowing for cultural and ethnic differences to be protected and encouraged, as opposed to attempting to institutionalize assimilation as the means to integrate new immigrants. In 1993, the Department of Multiculturalism was dismantled, and its portfolio was transferred to the newly created Department of Canadian Heritage.

Since then, several government policies and programs have attempted to address multiculturalism and racism in Canada, such as Black History Month, Asian Heritage Month, Historical Recognition programs to commemorate and educate “Canadians” about the historical contributions of various ethno-cultural communities. Furthermore, under Canada’s Action Plan Against Racism (CAPAR) $56 million has been allocated over five years (2005–2010) to programs and initiatives built around anti-racism education, financial assistance for marginalized groups and communities, and victim assistance. Under CAPAR, CIC has also created the Welcome Communities Initiative (WCI) in order to support programs, organizations, workshops, and online resources aimed at alleviating barriers and discrimination new (im)migrants may face.

While the liberal agenda to institutionalize multiculturalism was well-intended, it can often lead to stereotyping of, and hence discrimination against, different immigrant cultures and ethnicities. Celebrations of multiculturalism often essentialize cultures by focusing on cuisine, festivals, and holidays “unique” to one’s culture; in other words, they often glaze over the complexities and intricacies of cultural groups in order to showcase oversimplified differences (Abu-Laban 2002; Kernerman 2005; Richmond and Saloojee 2005; Satzewich and Wong 2006; Reitz et al. 2009).

Furthermore, the institutionalization of multiculturalism has been criticized not only by immigrants groups but by Quebecois and Aboriginal peoples as well. Since its inception, many Quebecois groups have criticized and resisted multicultural policies; they argue that it equates Quebecois to an ethnic minority culture, and continues to subject them under the domination of Anglo-Canada as opposed to upholding an equal relationship with them (McRoberts 2004; Dewing and Leman 2006). The Quebecois’ criticism of multicultural policy as “downgrading” to their status and relationship with Anglo-Canada is symptomatic of another problem: the undermining and ignorance of Aboriginal peoples’ rights to sovereignty and land. In particular, the Canadian government perceives Aboriginal peoples as a piece of Canada’s multicultural mosaic. They equate Aboriginal peoples with settlers – a problematic formulation which ignores Canada’s colonial past and present – instead of recognizing their right to inherent sovereignty. By imposing multicultural policy onto Aboriginal communities, Canada continues to subject Aboriginal peoples to an ongoing colonization, in which Aboriginal people’s land and sovereignty claims are negated. With immigrant communities, starting from the premise of Canada as one coherent nation-state Official Multiculturalism tries to add on and fit in those who have arrived “recently”.

Having elaborated on the key concepts, we move now move to describe immigration policy categories, and their linkages to industry and labour markets, as they intersect with gender, race-ethnicity and class.

Immigration Policy Categories

In this module, the term immigrant is reserved for those “landed immigrants” who are granted permanent residency or refugee status. In contrast, migrant is an umbrella term used for those in Canada who have no status at all, who enter under temporary programs or who enter as a landed immigrant. The concept of immigrant recognizes the formal constraints the Canadian state places on entry and settlement; it is also the primary category used by Statistics Canada (see “data sources and indicators” section).

Permanent Entry Categories

People who enter Canada as permanent residents are further divided into specific categories. Each category is organized through a particular regulatory framework, which sets the terms and requirements of entry. The module uses CIC’s terminology.

Immigrants

The broad category of “immigrants” includes a number of sub-groups united by their entry based mainly on their potential economic involvement in Canada in order to support general or specific economic needs of Canada.

Investors, entrepreneurs, and self-employed people (previously “business immigrants”): The entry of these individuals is based on their economic ability to establish themselves through entrepreneurship, self-employment or direct investment.

Skilled workers and professionals (previously “independent immigrants”): These individuals are chosen on the basis of their ability to participate in the Canadian labour market. A selection model emphasizes factors such as education, official language proficiency and skilled work experience. Quebec, independently from the rest of Canada, selects its own skilled workers.

Provincial or territorial nominees: These are individuals, with specific skills, who are selected by a province or territory to address a specific local labour market need. Provinces enter agreements with CIC to nominate a certain number of workers.

Live-in-caregivers: Depending upon the regulation in question, the live-in-caregiver category (discussed below) is included simultaneously in the list of “immigrants” categories and categories of temporary migration since although they migrate to Canada as temporary workers, and must live-in with their employers for a specified period, they are permitted to apply for residency from inside Canada.

Family class immigrants: This group includes spouses and partners; parents and grandparents; and dependent children (those under age of 18) who are sponsored by a Canadian citizen or permanent resident in Canada. It can also include the guardians of the sponsor. This class is not economically-driven; however, the sponsor must prove that they are able to provide those they sponsor with sufficient financial support.

Canadian Experience Class: Introduced in 2008, this class allows students and high-skilled workers entering on a temporary basis to apply for permanent residency (outside of Quebec) after two years of studying or working in Canada. Applications are assessed on official language proficiency as well as work and/or study experience.

Refugees

Canada chooses refugees from abroad and also responds to those people who come to Canada and claim to be refugees. The selection of refugees abroad, by the Canadian government, has been criticized “for choosing offshore refugees who are well educated and able-bodied and therefore likely to quickly become contributors to the Canadian economy” (Dauvergne 2005: 93). Refugee claims made by individuals in Canada are considered by the Refugee Protection Division (RPD) of the Immigration and Refugee Board (IRB).

The refugee category includes three sub-categories as per the CIC definitions.

Government-assisted refugees (also known as having resettlement from outside Canada): These are people who are selected abroad for resettlement to Canada, and who receive resettlement assistance from the federal government. There are three legal processes (also referred to as three separate refugee categories) for admitting government-assisted refugees:

i. Convention Refugees Abroad Class: these are people outside of the country in which they usually live and to which they cannot return back.

ii. Country of Asylum Class: this class is for people who are in a similar situation to convention refugees (i.e. who live outside their home country), but do not qualify under that class. Specifically, it is intended for groups of people who are affected by civil wars and armed conflicts.

Source Country Class: this is for people who are from a country that is identified by the Canadian government as a source country of refugees, and who are living in their home country at the time of applying for resettlement.

Privately sponsored refugees: These are people selected abroad for resettlement to Canada through private sponsors and who receive resettlement assistance from private sources. They must be sponsored by a Canadian or a permanent resident, and they can be sponsored by individuals, community groups, or groups of 5 or more individuals. Additionally, there is a Joint Assistance Sponsorship program which allows organizations to sponsor a refugee in conjunction with CIC.

Refugee protection claimants: These are people who have arrived in Canada and are seeking protection. If such a person receives a final decision that he or she has been determined to be a “protected person,” he or she may then apply for permanent residence. This class of refugee is temporary pending a decision on their claim, unlike the other refugee categories which are permanent with regards to residency in Canada.

Once a refugee claimant enters Canada and receives a hearing with the IRB, they can either be accepted as protected persons or rejected. In the case that a claim is rejected, there are limited procedures to appeal the IRB’s decision. The applicant can apply to the Federal Court of Canada for a judicial review, a pre-removal risk assessment (PRRA), or under H&C considerations. A PRRA gives refugee claimants approximately 15 additional days to prove that the country they are supposed to be sent back to is unsafe for them. Applying for permanent residence through H&C grounds, on the other hand, can take many years and is the last option a refugee claimant has before being deported. If a claimant has at least one child, they can also apply under H&C grounds for the Best Interests of the Child (BIC).

Temporary Entry Categories

In Canada, temporary migrants are divided, similar to the permanent immigrants, into specific sub-categories, whose terms and requirements of entry are organized through a particular regulatory framework.

Humanitarian class: These are temporary residents admitted to Canada on humanitarian grounds. They occupy an intermediate status, between temporary and permanent, as they await a conclusion to the refugee determination process.

Students: These people are in Canada on time-limited temporary student visas, which restrict their capacity to engage in work for pay. For example, many non-nationals enrolled full-time in a Canadian postsecondary institution were only permitted to work on a university or college campus for a fixed number of hours per week. Presently, certain foreign students are able to work up to 20 hours per week off-campus during the school year, and full time during scheduled breaks. Since the introduction of the Canadian Experience Class, students can also apply for permanent residency directly after completing their degree and living in Canada for at least 2 years.

Temporary migrant workers: This is a highly heterogeneous entry category. Temporary migrant workers must obtain a permit to engage in paid work in Canada. CIC normally authorizes this permit after the applicant receives a formal job offer approved by Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC; previously under the Department of Human Resources and Social Development, now split into Service Canada and Department of Human Resources and Skills Development) on the basis of a prior labour market opinion, based on assessment criteria set out jointly by these two federal departments. Certain groups, however, are exempt from the typical requirement for a work permit, and the certification process it entails, such as individuals with work authorization privileges under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

CIC uses the terminology “temporary foreign workers” interchangeably with “temporary workers.” This module specifically employs the term temporary migrant workers for two reasons: first, to differentiate this category of workers, as defined by government policy, from any worker, whether a migrant or not, engaged in temporary employment (a form of employment examined in the precarious employment module); and second, to emphasize the many coexisting and overlapping regimes of (im)migration in Canada and their relationship to gender and work. The avenue through which a migrant enters Canada, specifically one’s entry category, is linked with how (un)successfully a migrant incorporates into the labour market. The increasing demand and recruitment for temporary migrant workers, for example, greatly restricts the migrant’s long-term incorporation into Canada’s labour market.

Temporary Migrant Work Programs

There are several different types of temporary migrant worker programs (known as “temporary foreign worker program” in official policies, previously referred to as “foreign worker programs”) in Canada. Historically, these programs have grown out of “temporary labour needs” defined by the federal government and identified in labour market and immigration policies and the resulting pilot projects such as the Low-Skilled Pilot Project (see “Low-Skilled Pilot Project”). In practice, HRSDC works with CIC to set out these needs with varying levels of input from industry and labour markets.

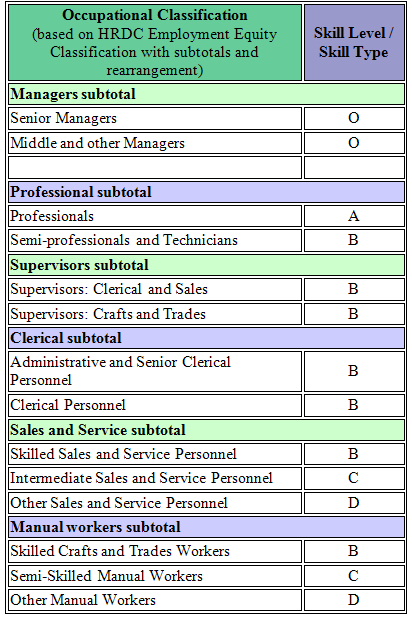

Most temporary migrant worker programs centre either on a specific occupation, a set of occupations, or a sector. Programs cover such diverse groups as foreign academics, agricultural workers, health care workers, live-in caregivers, entertainers, construction workers, workers in tourism industry, engineers, and families (only alongside a temporary worker application). There is also a program that covers workers in a range of occupations that usually require a high-school diploma or job-specific training. This program allows employers to offer term-limited employment (normally for one year, and for two in some cases) to workers with, at most, either a high school diploma or two years of job-specific training in occupations falling under Skill Levels C and D of the National Occupational Classification (NOC) system defined by Statistics Canada (see “occupational polarization” in “data sources and indicators” section).

Normally, official policies pertaining to these programs set out criteria and/or guidelines for hiring workers on a temporary basis, detailing steps in the approval process and time limits for permits. In most cases, temporary migrant workers require a job offer and work permit before coming to Canada, specifying different types of employment, employer and time period. Employers, in turn, are required to obtain HRSDC certification indicating the impact of hiring temporary migrant workers on the Canadian labour market. In some instances, normally where there is an industry-wide labour shortage, programs exempt individual employers from HRSDC’s evaluation of the impact on the Canadian labour market. In such cases, memoranda of agreement between industry, labour and government are used as tools to govern recruitment on a sector-specific basis (e.g., through the Software Human Resource Council, the SAWP). In others, a given agency of the provincial government agrees to oversee recruitment, placement, and terms of employment (e.g., the Ontario College of Pharmacists). Such programs fast track the admission of certain temporary migrant workers. In other cases, trade agreements may facilitate cross-border mobility of temporary migrant workers; for example, Chapter 16 of the North American Free Trade Agreement permits workers in sixty-three occupational categories to work in Canada with a work permit specific to the agreement, without requiring certification from HRSDC.

While temporary worker programs are diverse, one longstanding and unique (both for the conditionalities attached and the pathways it provides to permanent residence) program is particularly relevant to the study of gender, work and migration in Canada: the LCP.

LCP

The LCP is a longstanding and extensively researched program allowing individuals to employ live-in caregivers in Canada to care for children, elderly people or people with disabilities (see for example: Arat-Koc 1989; Stasiulis and Bakan 2003). Temporary workers, mainly women, who meet requirements for language, education and work skills set out by CIC, are eligible to apply and many gain access to this program through recruiters, largely private employment agencies, in their country of origin.

The IRPA includes special guidelines for the hiring of live-in caregivers in Canada. These guidelines require domestic workers to work full-time in a single private home and live with the employer (and be provided with a private, furnished room in the home). Live-in caregivers are not permitted to work for more than one employer at a time, for a health agency, for a labour contractor, in day care or in foster care. While these workers obtained the right to organize and bargain collectively in the 1990s in Ontario (Fudge 1997) they are excluded from many statutory protections and social benefits; furthermore, they cannot unionize until the Employment Standards Act is amended to allow for single-employee bargaining units. However, unique among other programs, live-in caregivers migrating to Canada as temporary workers are eligible to apply for permanent residence in Canada after working for two years in a private home.

The case of live-in caregivers illustrates that temporary work programs provide differential levels of access, as well as access points, to permanent residency, and ultimately to citizenship in Canada. In other words, live-in caregivers are permitted to access permanent residency after a specified period of living and working in Canada, and they are not required to leave the country to shift from temporary to permanent status. This change in policy grew out of extensive lobbying efforts on the part of women’s organizations and non-profit organizations advocating for the rights of caregivers and immigrants (Bakan and Stasiulis 1997); struggles on the part of organizations such as Toronto-based Intercede and the Vancouver-based Committee for Caregivers and Domestic Workers’ Rights and campaigns endorsed by such groups as the National Action Committee on the Status of Women in the 1980s and 1990s. As a result, while access is not automatic, federal government policies assume that most of those (mainly women) migrating as live-in caregivers will seek permanent residency and ultimately Canadian citizenship. The situation of these migrant workers highlights the sometimes porous nature of the relationship between permanent and temporary migration (Arat-Koc 2001; Goldring, Berinstein and Bernhard 2009; Langevin and Belleau 2000; Oxman-Martinez, Hanley, and Cheung 2004; Sharma 2006). (see also “Immigrants”).

Furthermore, while the LCP is a federal program, live-in caregivers are protected under provincial employment standards and policies. For example, in Ontario they are protected under the Provincial Employment Standards Act 2002 and the Occupation Health and Safety Act (OHSA). However, regulations regarding LCP are constantly in flux both at the provincial and federal levels, affecting how it operates within various provinces, how live-in-caregivers are recruited and protected. In some provinces, for instance, recruiters may be able to charge live-in caregivers for their services, or the recruitment fees can be quite costly, thereby further disadvantaging an already precarious group of migrant workers. The changing LCP regulations at both the federal and provincial level also lead to tensions and dissonances between provinces, as well as between provincial and federal policies. Such dissonances also characterize programs geared towards migrant construction workers.

While the boundaries between temporary and permanent categories are porous (Stasiulis 2008; Goldring, Berinstein and Bernhard 2009), especially under LCP, there is no general provision for attaining permanent residency in the temporary migrant worker program for migrant workers engaged in other occupations deemed “low-skill”. Canadian immigration policy, through its entry categories, attempts to control the flow of migrants into Canada by setting out the conditions and limits of their entry, incorporation in labour market and settlement. In modifying and creating new categories of entry into Canada, at present there is a shift in federal policy away from skill-based permanent immigration to more low-skill based temporary migration. This is altering immigration to Canada in providing short-term solutions to long-term labour shortage problems, with a focus on temporary workers and devolution of decision-making powers away from what had been a federally-driven immigration model of permanent residency.

Immigration Categories, Industry and Labour Markets

Skill-based Immigration Policy

The prevalence of skill-based immigration policy affects migrants’ entry into Canada as well as their labour market integration (Boyd and Thomas 2002; Gabriel 2004; Reitz 2001a; Simmons 2005). Through the lens of schooling (Simmons 2004) or the newly constructed skill-based policy categories (Gabriel 2004), researchers can consider how changes in policy influence gender, class and racial inequalities in labour market positions. For instance, many new immigrant women are deskilled, or have skills that are underutilized, due to policies and systemic barriers which make it difficult for their incorporation in the labour market. Immigrant women, as a result, tend to be employed in menial, precarious, and part-time positions (Estévez-Abe 2005; Iredale 2005; Man 2004; Raghuram 2004; Reitz 2001b). Furthermore, in recent years there has been an increasing need for “unskilled” or “low-skilled workers”, such as agricultural, construction, and service-sector workers, which also contributes to the underutilization of immigrants’ skills. Some PNPs as well have been employed in every province and territory to help employers recruit such workers. For example, Saskatchewan heavily recruits lower-skilled employees.

Labour Force Participation

Labour force participation is another lens to examine the mismatch between skill-based immigration policies and the location of migrants in the Canadian labour market, one that brings gender to the center of analysis. Labour force participation “marks the transition from unpaid to paid work, the point at which the public and domestic spheres intersect” (Giles and Preston 1996). Due to its intersection with gender relations in households and families, the labour force participation rates of skilled immigrant women still lag behind those of skilled immigrant men, particularly for recently arrived immigrant women (Giles and Preston 1996).

Mode of Labour Market Incorporation

Policy also influences the mode of migrant and immigrant incorporation into host labour markets (Portes and Bach 1985). Labour market incorporation refers to the entry, position and degree of progress of incorporation of migrants in the host labour market, including their entry into occupations and ability to translate their education and training into upward socioeconomic mobility, or not. An issue that has continually escalated in the past twenty five years is the “underutilization” of immigrants’ skills. On average, despite having higher education and skills than Canadian-born individuals, recent immigrants often have more difficulties incorporating into the labour market. As a result, new immigrants tend to earn lower wages, as well as have higher poverty and unemployment rates compared to Canadian-born individuals (Reitz 2005).

The Canadian government introduced a Foreign Credential Recognition program (FCR) in 2004, and created a Foreign Credentials Referral Office in 2007, in order to increase employers’ awareness of inequalities facing migrants and to help internationally trained individuals get their skills assessed and recognized more quickly. However, the degree of mobility among migrants in host economies is shaped by the mode of their initial entry into the economy, including whether they enter as permanent immigrants or temporary migrants. It is also shaped by the structure of the economy at the time of their entry.

Industrial Restructuring

Industrial restructuring is used to refer typically to the decline in manufacturing jobs and a shift to a service-based economy. Some scholars emphasize the emergence of a “post-industrial sector” and stress its difference from the older industrial sector (Myles and Clement 1994). Others focus on the “service complex regime” that characterizes global cities (Sassen 1996). Both concepts are useful to examine how migrants are incorporated into restructuring economies. Gendered analyses of industrial restructuring reveal that migrant women, particularly recently arrived women of colour and those without legal status, are incorporated into the low paid jobs in both the “post-industrial” service sector and the older industrial sector (Myers and Cranford 1998; Gabriel 1999; Giles and Preston 1996).

Occupational Polarization

Industrial restructuring has also shaped occupational polarization. While the older “blue collar” unionized jobs in the manufacturing sector have shrunk, both very low-end and very high-end occupations in the service sector have grown (Sassen 1996). Occupational polarization is one facet of the feminization of employment norms (Vosko 2000). This facet has a key influence on migrant women of colour in both wage work and self-employment (Cranford and Vosko 2006; Vosko and Cranford 2004).

Precarious Employment

The growth and spread of precarious employment, that is forms of employment normally involving atypical contracts, limited social benefits and statutory entitlements, job insecurity, low job tenure, low wages, and high risks of ill health is another central dynamic of change in the Canadian economy (Vosko 2000 and 2006; Vosko, Zukewich and Cranford 2003). Migrant women, and some men, of colour are incorporated into jobs that are highly precarious along multiple dimensions (Cranford, Vosko and Zukewich 2003; Cranford and Vosko 2006).