unions

CONCEPTUAL GUIDE TO THE UNIONS MODULE

Prepared by Linda Briskin, Leah F. Vosko, Hans Rollman and Marion Werner with contributions from Vivian Ngai and Karen Foster

Unions are a key labour market institution. They have an impact on activities in households and workplaces, and influence education, health and social care, and public policy. Unions are also social movements operating at multiple levels and geographies and seeking justice, equity, and inclusivity. As such, unions are central to any analysis of gender and work.

The Unions Module provides tools for researchers and activists to explore unions as both institutions and social movements. Its multiple components address union renewal, organizing the unorganized, leadership and representation, worker, labour and union militancies, international solidarity, the union advantage, and the regulatory context in which Canadian unions operate.

The module includes a conceptual guide, which explores, among other things, key concepts and offers a demonstration (on union advantage) of how researchers may use the module to address a particular research question. The guide also includes multidimensional statistical tables; a unique set of equity resources from Canadian unions; an extensive webography; and research papers on key themes. Through these components, the module is designed to facilitate analyses of unions in relation to complex social locations of workers at the intersections of gender, race, ethnicity, class, and other axes of difference.

INTRODUCTION

Unions are a key labour market institution. They impact on activities in households and workplaces, and influence education, health and social care, and public policy. Unions are also social movements operating at multiple levels and geographies and seeking justice, equity, and inclusivity. As such, they are central to any analysis of gender and work.

In recent decades, unions have been transformed by internal pressures rooted in membership-led initiatives (Briskin and Yanz 1983; Humphrey 2000; Cranford et al. 2005; Fine 2005; Cranford et al. 2006a; Bairstow 2007; Burawoy 2008), and external factors such as economic conditions, legislation and policies, and globalization (Lee 2005; Eaton and Verma 2006; Kapoor 2007; Bonacich, Alimahomed and Wilson 2008; Franzway and Fonow 2008).

This conceptual guide begins by exploring key concepts: equity, union renewal, organizing the unorganized, leadership and representation, worker, labour and union militancies, international solidarity, and the union advantage. It then examines the impact of national and international regulatory mechanisms on Canadian unions and the efforts of unions to shape them. Against this backdrop, it reviews data sources from Statistics Canada and Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC). The module’s equity resources from Canadian unions, an extensive bibliography of archived material, a series of relevant research papers and a related webography are also described. The guide concludes with a demonstration on the union advantage using the tools of the module.

KEY CONCEPTS

Equity

Unions are uniquely situated to promote both social transformation and the institutional mainstreaming of equity. Unions undertake collective bargaining and external campaigns to transform the conditions of work and workplaces, and to promote social justice more broadly. They simultaneously engage in institutional transformations to re-shape their internal workings around policies, practices and culture. Not only do unions operate as equity vehicles through collective bargaining, they also can model institutional change.

The language of “equity” rather than “equality” rests on the difference-sensitive meaning of equity in legal and policy contexts in Canada (from the important 1984 Abella Commission on Equality in Employment). Equity is used to acknowledge that sometimes equality means ignoring differences and treating women and men the same, and sometimes equality means recognizing differences and treating women and men differently. Equity refers, then, to what is fair under the circumstances (also called substantive equality and in contrast to the more narrow formal equality).

Five themes emerge in the consideration of trade unions as vehicles for collective agency and equity. First, trade unions act as vehicles for changing workplace relations and conditions through collective bargaining. Second, by negotiating equity provisions into collective agreements, unions have contributed to policies and research, which shape public debate surrounding equity (Fudge and McDermott 1991; Hart 2002, Briskin 2006a). For instance, the Canadian Union of Public Employee’s (CUPE) work on equity in pension plans in the late 1990s eventually led to national recognition of same-sex spousal benefit entitlements (CUPE 1998). Unions have also played a significant role in lobbying federal and provincial governments to introduce equity-based legislation.

Third, more than any other social institution, unions have undertaken democratizing initiatives to transform their organizational practice and culture in order to ensure fairness and representation. Fourth, trade union commitments to equity are expressed in union policy and constitutions/rule books. Over the last forty years, the Canadian union movement has produced extensive materials on equity-related issues, and the last decade has witnessed a remarkable development of union policy on racism, homophobia, sexism, and recently on transphobia and ableism (see Hunt and Rayside 2007; Eaton 2004). Preliminary research on equality-related language in twenty Canadian union constitutions reveals an increasing codification of equality in clauses on general equality, mandated equality-seeking committees, harassment procedures, leadership programs such as designated seats for members of equality seeking groups, childcare support at union meetings, and staff support for equality-seeking initiatives.

Finally, unions operate as equity resources at multiple levels and geographies, that is, at local, regional, national and transnational levels. For example, in 2007, the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), which represents 82 trade union organizations in 36 European countries, plus 12 industry-based federations, adopted a Charter on Gender Mainstreaming in Trade Unions which states that “[g]ender equality is an essential element of democracy in the workplace and in society. The ETUC and its affiliates confirm their commitment to pursue gender equality as part of their broader agenda for social justice, social progress and sustainability in Europe, and therefore adopt a gender mainstreaming approach as an indispensable and integral element of all their actions and activities.”[1]

The positive impacts of union equity initiatives can be seen in union renewal efforts, shifts in representation and leadership, international solidarity initiatives, and the union advantage.

Union density

Unions have faced unprecedented challenges to their ability to defend workers rights and improve workplace conditions as a result of neoliberal state and market restructuring (Porter 2003; Bezanson 2006; Vosko 2006). Union membership, as well as overall union density, has declined throughout North America and other parts of the world.[2] In the United States, union membership dropped by nearly half, from 20.1% in 1983 to 12.7% in 2007, among all wage and salary workers (Walker 2008). Yet, unlike density declines experienced in countries like the US and the UK, union density in Canada has remained relatively stable. In 2004, for the first time, the unionization rate for women (31%) was slightly higher than it was for men (30%) (Morissette, Schellenberg and Johnson 2005: 5-7). This trend continues. In 2010, the rate was 32.8% for women and 30.4% for men (Statistics Canada 2010).

Sectoral demographics are also significant. In the public sector where women are predominantly clustered, 74.8% of workers belong to unions compared to only 17.5% in the private sector (Statistics Canada 2010). Peirce (2003: 273) points out that “[p]ublic sector union members are much more likely than their private sector counterparts to be female, professional, and white-collar.” The increase in public sector unionism, then, represents a shift in both the gender and class composition of the Canadian union movement.

Given these trends, it is not surprising that by 2002, women comprised half of all union members in Canada thus suggesting the feminization of union density and a concomitant feminization of unions (increasing numbers of women union members). Milkman (2007) documents similar trends in the US, and the European Industrial Relations Observatory (EIRO) notes that, in 2006, “the proportion of female union members has now surpassed that of male union members in a number of EU Member States.”[3] Union density also varies across different forms of employment, as well as by industry, and occupation. According to Statistics Canada (2010), overall unionization rates increased between 2009 and 2010 for full-time workers (to 31.1%) and part-time workers (to 23.5%). Workers in permanent employment have higher union density rates (30%), compared to those in non-permanent employment, who have seen a decrease in unionization rates from 2009 to 2010 (to 27.3%). Women have higher unionization rates than men across all forms of employment (full-/part-time; permanent/non-permanent) (Statistics Canada 2010).

Cross-industry and occupation differences in unionization reflect a significant public/private divide (Jackson 2010). In Canada, the highest union density rates are in public administration (68.5%), education (67.0%), and utilities (61.6%) industries. The lowest rates are in agriculture (2.7%); professional, scientific and technical (4.2%), and accommodation and food (7.0%) industries (Statistics Canada 2010). It is important to also consider employment form when looking at these statistics. For example, agriculture is most commonly comprised of self-employed men. Across occupations, the highest union density rates are found in occupations in the fields of health (60.2%), and social science, education, government (55.4%). Secondary and elementary school teachers (85.9%) and nurses (78.5%) have the highest unionization rates, notably highly feminized domains. Occupations with the lowest union density rates are in management (8.3%), those unique to the primary industry (14.6%), and sales and services (21%). Whole sales and services jobs have the lowest unionization rate (5.5%) among all occupations (Statistics Canada 2010). Because the industries and occupations with the highest union densities are ones in which women are highly represented, women have a higher unionization rate overall than men.

Union density also varies across social location. For example, the unionization rates of visible minorities lag about 10 percent: approximately 20% compared to 30% for non-visible minorities (Cheung 2006). This gap is slightly larger for men than for women (Reitz and Verma 2004). Furthermore, visible minority workers who are unionized earn lower wages than their white counterparts (Cheung 2006). Immigrant status also relates to visible minority status; although immigrants have lower union density than their native-born counterparts, the difference varies according to period of immigration for both men and women. Recent immigrants (both whites and visible minorities) have the lowest rates, whereas those who have been in Canada longer have higher rates (Reitz and Verma 2004). Such patterns in union density point to disadvantages that some workers face in relation to their social location.

Union renewal

Unions are using new strategies to increase their overall membership and strengthen their ability to represent their constituencies (Foley and Baker 2009; Kumar and Schenk 2006). These strategies include organizing the unorganized, democratizing union practices, and building strategic alliances with community activists and international partners. These clusters of initiatives are often referred to as “union renewal“. Where unions have often seen internal transformation as irrelevant to the project of workplace change, within the union renewal paradigm unions recognize the complex interrelationship among re-shaping themselves organizationally and institutionally, effectively defending the rights of their members, both as citizens and wage earners, and recruiting new members.

In the context of economic restructuring and direct attacks on unions, unions have become more active in trying to organize women to strengthen their membership base. Concomitantly, women workers are increasingly committed to gaining the protection of union status, and have initiated and led some very militant strikes for first contracts.

Organizing the unorganized

In response to shrinking membership and density, unions are seeking to recruit new members by organizing the unorganized. Although workers in Canada have the formal right to be in a union, access to union representation depends upon an adversarial certification process. Organizing a union is a difficult, lengthy, and often an unsuccessful undertaking. Furthermore, the entrenchment of right-wing governments with anti-labour agendas have enhanced the ability of employers to prevent unionization (Panitch and Swartz 2003). Should an organizing drive be successful, employers often resist the negotiation of a first contract, despite the existence of first contract arbitration in some jurisdictions. Organizing the unorganized, then, is a major problem for Canadian unions. For women and immigrants who often work in difficult-to-organize sectors and locations (small workplaces, part-time work, in private service, in retail and financial sectors) union drives pose a special challenge.

Unions have approached organizing the unorganized in a variety of ways. Some unions have sought to expand beyond their traditional sectors or industries to those with large, unorganized workforces (Yates 2002). Examples include industrial unions organizing non-profit social services (Baines 2010), public service unions organizing casino workers or security guards (PSAC), manufacturing unions organizing university workers (CAW), or factory-based processing unions organizing migrant farm workers (UFCW). Rather than move to new sectors, some unions “follow the work,” organizing contracted services in their traditional sector (Stinson and Ballantyne 2006). New sites for organizing have also been identified across forms of employment among workers in so-called “non-standard employment” – also known as the precariously employed. These include organizing part-time, casual, temporary or self-employed workers, who may work in volunteer agencies, fast-food outlets, or call centres (Hunt 1999; Briskin 2006b; Cranford et al. 2005; Vosko 2006).

Unionizing the precariously employed is difficult not only because of employer resistance but also because legislation prevents organizing particular groups of workers, for example, live-in caregivers and other employees covered under Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program (Trumper and Wong 2007). As a result, some workplace unions devote resources to initiatives to organize unemployed or non-unionized workers without actively seeking to certify their workplaces. They build strategic alliances with community activists and international partners to pursue non-traditional methods of improving working conditions (Tait 2005; Tufts 2004; Cranford et al. 2005). Examples include strategic alliances with workers’ centers (for example, the Toronto-based Workers Action Centre, see Cranford and Ladd 2003 and Cranford et al. 2005), and international dialogue with self-employed workers’ groups (Vosko 2007). Union-community coalitions around non-traditional organizing, such as improving terms and conditions legislated under provincially based employment standards which typically serve as a floor of labour protections for non-unionized workers, also reflect efforts by unions to expand their social and community base to achieve broader political goals.

Leadership and representation

Mobilizing the multiple constituencies of unionized workers based on race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexuality, ability and First Nations status is central to the long term vigor of the Canadian labour movement. Many of these workers have traditionally been marginalized but are rapidly becoming a larger proportion of the unionized workforce, and their claims to union citizenship have been consolidating. Inside unions, a dual strategy for democratization via initiatives around leadership and representation has emerged: on the one hand, the election of more women and members of other equity-seeking groups to union leadership positions to change demographic profiles; and on the other, constituency organizing to represent the interests of women and other equity-seeking groups.[4] These two separate but not unrelated projects recognize that presence in and of itself does not ensure voice. Representational strategies that take up a practice of intersectionality and build new forms of solidarity through cross-constituency organizing are recent innovations (Briskin 2008). Certainly, the evidence suggests that increasing women’s participation in elected leadership positions is not sufficient to en/gender democracy in the unions, empower women, or offer inclusive unionism to any marginalized group.

Affirmative action (also known as positive action) programs, designated seats, fair representation and proportionality measures represent major union initiatives to address the demographic under-representation of women and members of other equity-seeking groups in top elected positions and are now widespread. In the 1990s, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU – now ITUC) reported that trade union centrals in Austria, Belgium, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Columbia, Dominican Republic, Fiji, France, Great Britain, Guyana, Israel, Italy, Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, and the Philippines all set aside special (sometimes called reserved) seats for women on their central leadership body (1991: 46-47; also 1994; see also Sechi on the ETUC 2007; and Trades Union Congress 2007 and 2011). The strategies of the British UNISON, Europe’s largest public sector union, which was born in 1993 of an amalgamation of three unions, are worth noting. Proportionality and fair representation are central to UNISON’s constitution, and special representational measures exist for women, black members, lesbian and gay members, and disabled members. In an important innovation, representative structures also provide seats for low-paid women (McBride 2001).[5] The widespread institutionalization of affirmative action programs have put proportionality discussions on the agendas of many unions; led to changes in union constitutions; and increased training and mentoring programs to support leadership by and of marginalized unionists.

Over the past forty years, constituency organizing inside unions, also called separate or self-organizing, has been a vehicle to enhance representation. It has brought together members of equality-seeking groups – women, people of color, Aboriginal peoples, people with disabilities, and lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgendered peoples—to increase their skills, self-confidence and political power. It is expressed organizationally in both informal caucuses and formal committees (the latter sometimes mandated by union constitutions or rule books): Human Rights Committees, Rainbow Committees, Aboriginal Circles, Women’s Committees and Pink Triangle Committees. Equity-seeking groups have organized in response to male and white domination; patriarchal, racist and homophobic union cultures; and hierarchical and undemocratic organizational practices in unions. Such self-organizing has helped to politicize equity-seeking groups and produce them as vocal constituencies. Counter-intuitively, separate organizing has not led to the ghettoization, or marginalization of equity concerns; rather, it has been a vehicle for mainstreaming equity concerns. For example, in Canada, through separate organizing, women have promoted women’s leadership, challenged traditional leaderships to be more accountable, encouraged unions to be more democratic and participatory, and forced unions to take up women’s concerns as union members and as workers – through policy initiatives and at the negotiating table (Hunt and Rayside 2007, Briskin 1999, 2006a and 2006b).[6]

The various separate committees and caucuses which have played a critical if often unacknowledged role in transforming Canadian unions over the last four decades are now beginning to invent new political and organizational ways to work collectively and collaboratively across various marginalized constituencies; what Briskin (2008) calls cross-constituency organizing. Cross-constituency organizing is a vehicle to develop institutional and political practices which take account of multiple, sometimes competing, identities (intersectionality), promote a culture of alliances, and enhance inclusive solidarity. It helps to prevent intersectional disempowerment, on the one hand, and on the other, advance the union equality project, deepen democracy, and revitalize unions.[7]

Militancies

Briskin (2010) identifies three types of militancy. Worker militancy highlights the collective organization and resistance among non-unionized and often marginalized workers, many of whom are women and workers of colour. Among these workers, militancy has taken a variety of innovative and extra-union forms that are of increasing importance in defending workers’ rights, given restructured labour markets, attacks by corporate capitalism, coercive state practices and the difficulties inherent in organizing precarious workers into unions.

Union militancy focuses on the politics of unions themselves. Inside Canadian unions, the growth in both social unionism which contests the narrow focus of business unionism on wages, benefits and job security, and social movement unionism which builds alliances and coalitions across unions and with social movements is evident. Movements of union women have been instrumental in both these shifts.

Labour militancy speaks to the organized and collective activism of unionized workers. Workers have gone on strike to improve the conditions of and remuneration for their work, and to defend their rights to union protection. They have used the strike weapon to resist not only employer aggression but also government policy. Strikes are not the only form of labour militancy. Hebdon (2005) maps other forms of labour militancy. He distinguishes among covert collective actions (such as sick-outs, slow-downs and work-to-rule), other collective actions such as claims of unfair labour practices, and individual forms of militancy around grievances. Workers are also engaging in whistle-blowing and building alliances with non-unionized workers to pressure employers to uphold employment standards (Cranford et al 2006b).

Demographic transformations in work, the workforce, union density and union membership set the stage for the feminization of labour militancy, that is, those involved in strikes are more likely to be women. This trajectory is particularly true in the public sector. The roots of this change are complex but certainly include the shift in union membership demographics toward the public sector, and the militant response to sustained attacks on the public sector which have included wage freezes and rollbacks, downsizing, contracting out and privatization, and assaults on public sector bargaining rights (Panitch and Swartz 2003). In fact, one might argue that the state has participated in the process of gendering militancy by its consistent and heavy handed attacks on the public sector. As Darcy and Lauzon (1983: 172-3) point out, “the right to strike is a women’s issue [given] the fact that organized working women are heavily concentrated in the public sector, where anti-strike legislation is directed.” Although statistics are not available that demonstrate the exact proportion of women and men involved in any particular strike, the growth and increasing feminization of the public sector, especially in health and education, the importance of public sector workers to union density, and the significance of strikes in this sector support the general claim for the feminization of militancy (Briskin 2007).

Unions are also being repositioned by the transnationalization of capital and the concomitant rise in corporate economic rights. Unions and workers’ movements are expanding their transnational organizing to include campaigning around international conventions and lobbying international organizations (e.g., the ILO) and supranational regulatory bodies (i.e. the European Union) (see for e.g., Vosko 2010 Chapter 5). As states relinquish their power to govern in key areas, and international bodies like the WTO support corporate economic rights and at the same time regulate nation states (Cohen 2007: 192), trade unions have become one of the few institutional counterpoints that can challenge states, transnational corporations, and international bodies.

In Global Unions: Challenging Transnational Capital Through Cross-Border Campaigns, Kate Bronfenbrenner (2007) documents campaigns to challenge the world’s largest transnational firms through strategic analysis of the structure and flow of corporate power within each company (such as Exxon Mobil, Kraft, Starwood, Wal-Mart etc.), and through cross border campaigns to build global solidarity. These campaigns, pro-active rather than defensive, offer hope in what is often a bleak landscape of corporate and neo-liberal state power. Bronfenbrenner (2007: 225) concludes that “[w]ithout question, a united global labor movement is the single greatest force for global social change and the single greatest hedge against the global race to the bottom when the unions reach across borders to realize that potential. Global unions are the future.”

International solidarity

Canadian unions are committed to international solidarity work. A few examples: Canadian unions supported the South African trade union movement through boycott, divestment and embargo campaigns during the apartheid era (Luckhardt and Wall 1980; TCLSAC 1986). More recently, unions (such as CUPE, the CLC, and PSAC) have supported the Colombian trade union movement. Since 2001, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) has developed strong links with Colombian public sector unions in an effort to draw attention both to the impact of public service privatization (occurring at an unprecedented rate in Colombia) as well as Colombia’s status as one of the most dangerous countries for trade union organizing (based on incidents of violence and assassinations of union leaders). These initiatives intensified since the negotiation and signing of a bilateral trade agreement between Canada and Colombia (CUPE 2009).

In her account of the RMSM (Red De Mujeres Sindicalistas de Mexico) (Network of Union Women of Mexico), Reyes (2007: 229) indicates that the RMSM was created in 1997 with 52 members and a coordinating committee drawn from eight participating unions, which was made possible by solidaristic support from the Canadian Auto Workers Union (CAW). Reyes shows that the collaboration with the Canadian unions was “based on the feminist workers’ perspective building on the triple identities as worker, woman and unionist.”

Union advantage

Although many elements determine wages and job quality (such as education, workplace size, industry, and so forth), union coverage is a key factor in improving wage levels and economic equality. Workers who are covered by a collective agreement often earn higher wages than comparable workers who lack such coverage (Aidt and Tzannatos 2002; Jackson 2010). They are also more likely to have better working conditions and more control over their work, access to health and pension benefits, opportunities for training, and some degree of job security through their collective agreements. The bundle of social benefits and entitlements beyond earnings that affect workers’ standard of living are often referred to as the social wage.

Unions also pursue goals around equality and non-discrimination measures (Hollibaugh and Singh 1999; Hunt 1999; Cohen and Cohen 2004; Anderson, Beaton and Laxer 2006; Crain 2006; Vosko 2006; Cambalikova 2007; Tufts 2007; Bonacich, Alimahomed and Wilson 2008). Finally, unions play a significant role not only in improving the material working conditions of their members, but also in raising the floor for pay, employment benefits and other working conditions that result in improvements in the social wage for the broader workforce (Anderson, Beaton and Laxer 2006; Crain 2006; Cambalikova 2007).

The union advantage demonstration below provides an example of a research question, which helps to assess the relationship between economic and social benefits, and union coverage (see Union Advantage Demonstration below).

Unions in Canadian and international regulatory contexts

Although labour is largely a provincial matter in Canada, regulations operating at federal and international levels also impact the workforce and unions, both facilitating and constraining union activity.

Federal and provincial regulation

In Canada, labour relations are regulated provincially (since 1925), and so each of the ten provinces and three territories has a distinct system governing certification processes, labour relations and work stoppages, occupational health and safety and essential services.[8] Although in some areas, there is commonality of legislation, provincial political cultures and histories have also produced significant differences, especially in the regulations covering provincial public sector workers. Workers in federally regulated or inter-provincial industries such as banks, railroads, and telecommunications are covered by the Canada Labour Code (about 10% of all workers); and those who work for the Canadian government are covered by the Public Service Staff Relations Act (PSSRA). In total, then, fifteen different systems govern labour relations in Canada, and fragmentation and decentralization are two significant aspects of the Canadian labour relations system. Certainly this structure has made widespread working class solidarity difficult (Heron 1996: 79).

It was only in 1944, more than a decade after the introduction of the 1935 Wagner Act in the United States, that Canada finally gave private sector workers the right to join unions. Originally a wartime measure to address labour unrest, PC1003 finally became a permanent statute in 1948 as the Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigation Act; within two years most provinces had passed similar legislation. In 1945, the Rand formula guaranteed some degree of union security through a system of union dues check-off. In return for union recognition and dues check off, management rights clauses in collective agreements gave employers exclusive control over the work process, and narrowed considerably the focus of what could be negotiated (Heron 1996: 78). With the exception of the province of Saskatchewan, which had a social democratic government and which gave collective bargaining rights to civil servants in 1944, it was only in the late 1960s that such rights were widely extended to the public sector. In 1967, the federal government passed the PSSRA which legalized collective bargaining for federal government employees. Within a few years, these rights were also afforded provincial public sector employees, including teachers and nurses, although in many instances the right to strike was severely limited. An underlying assumption of Canadian labour legislation is that outcomes should not be prescribed. However, in many jurisdictions, there are two exceptions: first, labour boards have the right to certify a union with the support of less than a majority of workers in instances of unfair labour practices by employers; and second, first contract arbitration exists in many jurisdictions in instances where employers have bargained in bad faith, and prevented the negotiation of a first collective agreement after union certification.[9]

Although major changes to labour law have been relatively minimal, what has been significant has been the growing intervention of the state into the management of labour relations, especially in the public sector. Panitch and Swartz (2003) argue that such state interventions challenge the very basis of free collective bargaining. The trend toward the adoption of various statutory incomes policies began with the implementation of compulsory wage and price controls in 1975 which led to a massive worker protest in 1976. Such policies have often been combined with back-to-work legislation and the increased designation of public sector workers as essential, thereby removing their right to strike. The National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE) and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) have launched a major campaign to defend free collective bargaining. They point out that since 1982 the federal and provincial governments have passed 170 pieces of legislation that have restricted, suspended, or denied collective bargaining rights.[10]

Finally, the Canadian industrial relations system cannot be fully understood without reference to the other side of what is actually a dual system. Non-unionized workers, many of whom are in precarious non-standard forms of employment, such as casual, and temporary work, are covered by weak provincial Employment Standards Acts (ESA), what Fudge has called “labour law’s little sister” (1991). These ESAs cover minimum wages, maximum hours of work, over-time rates, termination notice, and statutory holidays and, by the 1960s, maternity and parental leaves. The gendered significance of this bifurcated system is that the majority of workers covered under ESA, the considerably weaker of the two systems, have traditionally been women and other marginalized workers.

International regulation

There is an international dimension to both the legislative and regulatory context in which unions operate, as well as to their role as social movements. Canada is a member of the International Labour Organization (ILO), a United Nations institution in existence for over 90 years. The ILO has played an important role in establishing norms that surround labour and employment regulation, including the 2011 landmark treaty which sets out to protect the rights of domestic workers. In recent years, Canadian unions have become more assertive in using the ILO as a means to improve labour rights in Canada. Since 1982, Canadian unions have submitted more complaints to the ILO Freedom of Association committee than any other country in the world, alleging violations of ILO conventions by provincial or federal levels of government. Three quarters of these complaints deal with violations of freedom of association principles, including back-to- work legislation to end strikes which contravenes core international labour standards (Panitch and Swartz 2003; Fudge and Brewin 2005). Although the ILO lacks the ability to impose meaningful sanctions in response to violations by member states, the use of the ILO complaints mechanism has had an impact on how domestic courts interpret the constitutionality of government efforts to constrain union activities and limit work stoppages (Norman 2008). The most radical shift in the courts’ hitherto conservative interpretations of the scope of freedom of association rights under the Canadian Charter of Rights occurred in 2007, when the Supreme Court ruled that rights to organize and bargain collectively are indeed fundamental constitutional rights (Ibid.). The case, filed by health services unions in British Columbia contesting legislation passed by the BC provincial government is notable not only because the Supreme Court overturned previous anti-union rulings, but also because the court suggested that international conventions signed by Canada – including those of the ILO – must be considered in determining the interpretation of Charter rights (BC Health Services 2007; Matthews Lemieux and Barrett 2007; Norman 2008; Tucker 2008).

Growing efforts by governments to develop bilateral or multilateral treaties to facilitate international trade have also impacted unions’ policy initiatives and legal challenges. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Mexico, Canada and the United States provides a case in point. The accompanying North American Agreement on Labour Cooperation (NAALC) – the labour side-agreement associated with the NAFTA – provides limited mechanisms for filing complaints on the basis of eleven labour principles, including non-discrimination, freedom of association, occupational health and safety, and others. Some scholars argue that the transnational character of NAFTA and the requirement of NAALC that complaints be filed in a country other than the one in which the complainant is based have resulted, in some instances, in stronger cross-border cooperation between labour movements (Compa 2001; Kay 2011). Major challenges remain. Critics of the NAALC point to the restrictiveness of applicable sanctions and the fact that few cases are actually resolved (Ibid; Crow and Albo 2005; Franck 2008). (See International Solidarity above).

EXPLORING KEY THEMES: DATA SOURCES

Several Statistics Canada surveys allow researchers to examine key aspects of the relationships between gender, work and union coverage. The main surveys used in this module are described below.

Labour Force Survey (LFS) Many of the GWD tables relating to unions are derived from the Labour Force Survey (LFS). This survey divides the Canadian population into three mutually exclusive categories – employed, not employed, and not in the labour market – and presents descriptive and explanatory data on each. Its strengths are its regular monthly data collection and its considerable sample size of 50,000 households, resulting in comprehensive employment estimates on different forms of employment, as well as, for example, occupation, industry, hours worked, public/private sectors, work arrangements, wages, unionization, and firm size. The LFS also collects data on personal characteristics such as age, sex, marital status and education, along with variables related to the “economic family”. In January 2006, several questions were added to identify immigrant status, which is in the newer GWD tables.

Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID) The SLID is an annual survey developed with the objective of understanding the economic well-being of Canadians via data on labour, income and families. The SLID was initially a longitudinal survey, but the GWD only focuses on its cross-sectional component. The latter includes person-level variables like age, sex, education, immigrant status and activity limitations, as well as work-related variables such as income, wages, benefits, work schedule, occupation, employer attributes. The SLID also collects data at the household level, measuring “family and household” characteristics.

The Workplace and Employee Survey (WES) The WES is a highly specialized survey that provides data on the business strategies and organizational decisions of firms. The survey consists of two components: first, a workplace survey on the adoption of technologies, organizational change, training and other human resource practices, business strategies, and labour turnover in workplaces; and second, a survey of employees within these same workplaces covering wages, hours of work, job type, human capital, use of technologies, and training. Through these components, the survey allows analysts to link workplaces and their employees, thereby offering an important resource for studying the relationship between terms and conditions of employment among employees in unionized and non-unionized workplaces.

The WES offers interesting possibilities for studying labour disputes. It collects data on disputes and differentiates between work-to-rule, work slowdown, strikes, lockouts and other labour related actions. From the worker questionnaire, a profile of the striker emerges, and from the employer questionnaire, a profile of the firm facing labour action (for more on WES use, see Briskin with Klement 2004).

General Social Survey: Family Transitions; Cycle 20 (GSS) The GSS collects detailed information on the changing aspects of life in Canada and monitors the social trends and well-being of Canadians. Each cycle contains a core topic with a specific focus for analysis. Cycle 20 was conducted in 2006 and collected data specific to measuring household characteristics, familial structures, socio-economic traits and community demographics. Though the GSS is not a major contributor to the Unions module, it provides data on socio-demographic characteristics such as age, sex and aboriginal status, in addition to measuring union coverage and benefits.

For more information on labour disputes in the Labour Force Survey (LFS) and Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID), see Linda Briskin with Kristine Klement. (2004). “Excavating the Labour Dispute data from Statistics Canada: A Research Note.” Just Labour, 4, 83-95.

Administrative Data: Human Resources and Skills Development of Canada Data (HRSDC) The Human Resources and Skills Development Canada (HRSDC) is a department of the Government of Canada which works to develop policies, including those related to work, learning and the community. It is also a large source of information. Particular to this module are data collected on work stoppages and union membership in Canada.

DEMONSTRATION 1

The union advantage

The following demonstration illustrates how researchers may use the GWD to answer a research question related to unions, gender and work. The demonstration draws on all major components of the union module, including its multidimensional data tables, thesaurus, and library resources, and the research papers and union equity resources that are part of this module. It begins the examination of the “union advantage” by searching this term in the thesaurus. It then explores the wage component of the union advantage through data tables configured to cross-tabulate the dimensions of union coverage, hourly wage, sector, and sex. The second section of the demonstration shows how the union advantage extends beyond the wage. Using the GWD library, it considers claims advanced in the scholarly literature and highlights some of the non-wage benefits that unionized workers, especially women, have negotiated in their collective agreements. Finally, it identifies possibilities and limitations of available statistical data sources for addressing the issue of union advantage.

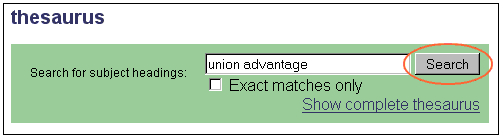

Part 1: searching for thesaurus and library resources

What is the “union advantage”, and how is it shaped by social relations surrounding gender and work? We might start to answer this research question by doing a thesaurus search on the term. A thesaurus search will provide us with a scope note, or definition, for the term, along with a list of other related terms, such as “employment benefits” or “union coverage”.

The scope note for “union advantage” defines the term as a set of benefits and protections for workers who are covered by a union. This may include better relative wages, benefits, job security, opportunities for promotion, and working conditions. Thus, the union advantage refers generally to the advantages that accrue to workers as a result of collective representation in the workplace.

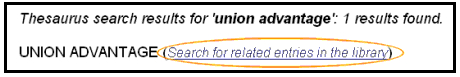

The thesaurus also provides a link to the GWD’s collection of library resources. Clicking on the link will take the user to a list of sources associated with the subject heading “union advantage”. Along with papers in the union module, a library search will help assist researchers in understanding the role that unions play in shaping wages and working conditions.

We see from relevant GWD papers such as Andrew Jackson’s “Gender Inequality and Precarious Work” (2004), that the union advantage has a number of important dimensions. This demonstration will focus on four of such dimensions: gender, occupation, sector, and wages.

Inequalities by gender as well as race-ethnicity, immigrant status, and age characterize the Canadian labour market. Although women increased their presence in unions in the post 1970s period, their pay, working conditions, and union protection still often lag behind men’s. One reason is that women remain concentrated largely in service industries such as health care, education, and in occupations such as clerical work and sales and services jobs. There is still a notable gap in earnings between men and women (Jackson 2004; Statistics Canada 2009). Canadian women earn, on average, 81% of men’s hourly wages.[11] The greatest part of the wage gap cannot be explained by objective factors such as educational attainments and job experience (Jackson 2004; OECD 2002; Drolet 2002). Rather, systematic earnings gaps between women and men, as well as gaps in benefits, opportunities for advancement and other measures of job quality, reflect continued job discrimination and under-valuation of women’s paid and unpaid work compared to that of men (Jackson 2004). As a result, many women experience higher levels of labour market insecurity.

Although there are many elements that determine wages and job quality (such as education, workplace size, industry, and so forth), union coverage is an important factor in improving wage levels and economic equality. In general, workers who are covered by a collective agreement earn higher wages than otherwise comparable workers who lack such coverage (Aidt and Tzannatos 2002; Jackson 2004). For example, women working in the private services sector, who are less likely to be covered by a collective agreement, receive lower wages than private sector men and public sector women. For these women, union coverage would likely result in significant improvements in pay. This wage advantage is also known as the union wage premium.

Economists have tried to calculate the union wage premium for comparable jobs, holding constant through sophisticated quantitative techniques all of the other factors that determine wages. Expressed as a percentage (of non-unionized wages), the union wage premium tells how much more a unionized worker in a given industry or occupation earns compared to a non-unionized worker. Calculated this way, the hourly union wage premium has recently been estimated to fall in the wide range of 2.5% to 54.7% in Canada in 2007, depending upon the industrial and occupational groups in which workers are found. On average, across all industries and occupations, unionized workers earn 24.2% more per hour than comparable non-unionized workers (Jackson 2010: 207). While these results are instructive and well-founded, they do not adequately drill down into the underlying structure of pay, including the effects of social location, intersectionality and gender differences. This type of more detailed analysis is made possible by the GWD, because the latter permits looking at union impacts while holding constant a few key dimensions such as gender, age, form of employment and occupation or industry. At the same time, it has to be borne in mind that even the multi-variate tables provided by the database conceal from view some other factors, such as disability, literacy, municipality, and some forms of social capital, which may partly determine relative wages but are not accounted for in data sources available.

Part 2: using statistical tables

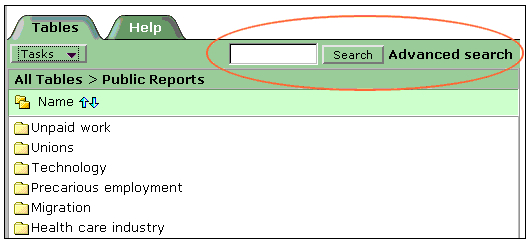

Begin this demonstration by searching for the dimension of union coverage, a dimension included in many statistical tables in the GWD. To find tables that include this dimension, researchers may choose from three options:

1. Do a search in the GWD library

2. Browse tables in the “Unions” module folder; or,

3. Search directly in the statistical tables section, as shown below.

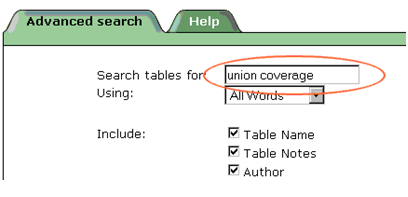

Users may also conduct an “advanced search” and specify which elements of the tables to search for their chosen terms.

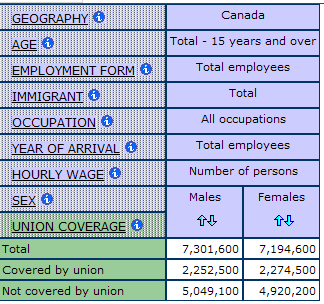

In this case, since the aim is to compare union versus non-union wages by sex, we want to find tables that include these dimensions. Table UN LFS-A2 2008, “Union coverage by sex and hourly wage, Canada and provinces, 2008 (UN LFS-A2 2008)” includes these dimensions. To bring up the table, click on the table’s title in the list of tables found.

Clicking on the information button next to the table’s title when viewing the table provides more information about the table itself, such as the survey used (in this case, the Labour Force Survey).

![]()

Let us look now at the “union coverage” dimension by gender using a simple table. As a first step, it is important to define “union coverage”. Users can search for the term in the GWD thesaurus to get a scope note. In this case, the term “union coverage” is defined by the GWD, and Statistics Canada, as employees who are members of a union as well as employees who are not union members but who are covered by a collective agreement.

In its questionnaire, the Labour Force Survey asks whether workers belong to one of three categories:

a. union member

b. not a union member but covered by a collective agreement

c. not a union member, and not covered by a collective agreement

In these tables, the first two categories are combined to get a broad sense of “union coverage”. Aggregating the categories in this way means that the number of workers covered by a union is slightly higher than the number of workers who actually belong to a union. When using these data, researchers should be aware of this conceptual distinction, which highlights the importance of careful examination of statistical categories and reference to relevant survey documentation.

The following is a table depicting union coverage by sex, hourly wage, year of arrival, occupation, immigrant status, form of employment and age, for Canada, 2008.

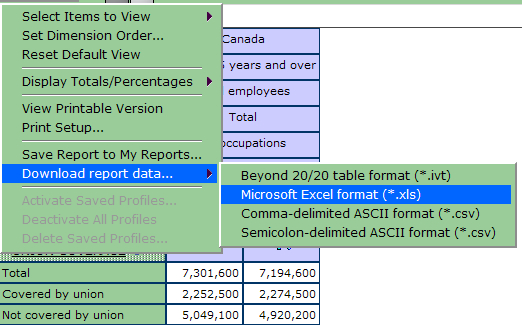

To convert the data to percentages, click the “Tasks” button at the top left. Click “Display Totals/Percentages” to show row and column totals, or download the table into Excel for further manipulation.

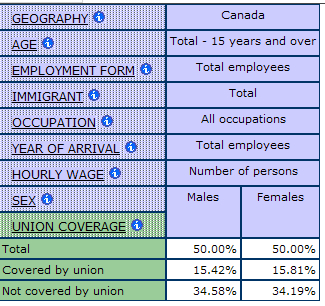

Part 3: calculating percentages

Remember that Beyond 20/20 takes all cells into account when calculating percentages. So, when calculating percentages for rows or columns, make sure that totals are not already displayed otherwise the program will compute the total in its calculations. To return to displaying numbers instead of percentages, simply toggle the option you have chosen by clicking on it again.

WRONG – total included in column percentage calculation

RIGHT – total not included in column percentage calculation

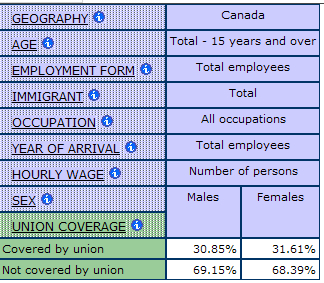

This table shows that about one-third of workers are covered by a union, with coverage levels slightly higher for women than for men; 30.85% of men and 31.61% of women are covered by a union.[12]

Now let us add another layer to the table. Click on the “hourly wage” dimension, deselect “number of workers” and select “median hourly wage”.

When examining wage data, using a median is often better than using an average, since a few extremely high or low values can skew the statistic up or down, presenting an inaccurate picture of most people’s earnings.

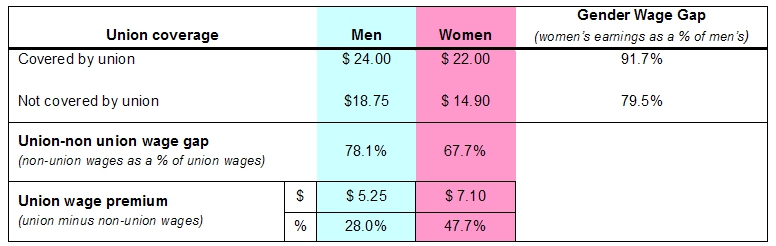

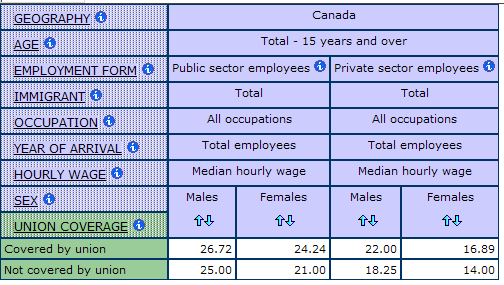

Table 1: Union coverage by Median Hourly Wage, Canada 2008

Downloading these data into Excel and performing a few quick calculations reveals three important findings:

1. Women earn less than men in both categories;

2. The hourly wage gap between women and men is larger among workers who are not covered by a union;

3. The union/non-union wage gap is more significant for women

It is now apparent that unions play a role not only in improving wages, but also in reducing gender-based wage inequality.

Table 2: Median Hourly Wages and Wage Gaps by Sex and Union Coverage, All Occupations, 2008

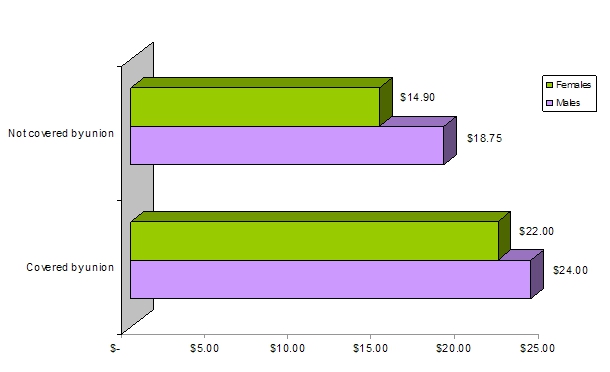

These relationships can also be expressed in chart form (as shown below in Chart 1).

Chart 1: Median Hourly Wages by Sex and Union Coverage, All Occupations, 2008

Chart 1 offers a very general idea of the relationship between union coverage, gender, and wages. Let us now add another dimension: sector. We know that whether a worker is located in the private or public sector is a significant determinant of wages and gender inequality (Archibald 1970; Morgan 1988; Fudge 2002). Wages are often higher for both women and men in the public sector, and women typically fare better in the public than the private sector given the poor quality of many jobs in the private services sector, where women workers remain concentrated. Public sector jobs are also more likely than private sector jobs to be unionized.

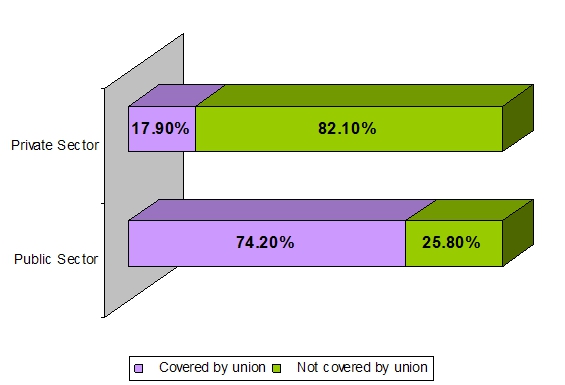

Let us look, then, at union density in public and private sectors. Start by selecting “public sector” and “private sector” in the “employment form” dimension (in this table, “sector” has been combined with form of employment; other tables include “sector” as a separate dimension). By cross-tabulating sector with union coverage, we can confirm that employees in the private sector are much less likely to be covered by a union than employees in the public sector: only about 18 percent of private sector employees are covered, compared to about three-quarters of public sector employees.

Chart 2: Union Density by Sector, 2008

The ratio of women to men varies by sector. In the public sector, about 62% of the workers are women; in the private sector, women make up about 46% of private sector workers. Thus, not only does the public sector have a higher union density, it also contains a higher proportion of women.

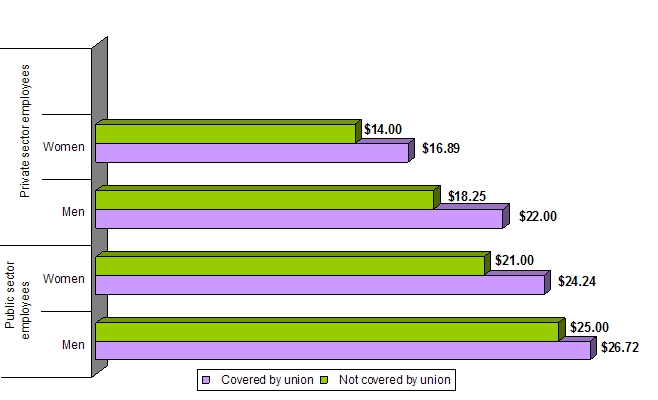

But does the upward leveling effect of union coverage on men’s and women’s wages depend on sector? Table 3 below suggests that it does.

Table 3: Median Hourly Wage by Union Status, Sector and Sex, All Occupations, 2008

Once again, these data can be copied into excel to create a chart and calculate differences:

Chart 3: Median Hourly Wage by Union Status, Sector and Sex, All Occupations, 2008

Chart 3 shows the difference between the highest and lowest wages for both men and women. What we see in depicting the results this way is that both sector and union coverage are relevant in shaping union wage premiums.

A first glance at the numbers indicate a few things:

i. women still earn less than men in all categories (i.e. public/private; union/non-union)

ii. workers in the public sector earn more than workers in the private sector

iii. union coverage provides little and least advantage for men’s wages in public sector work, although men in private sector work with coverage have the largest advantage

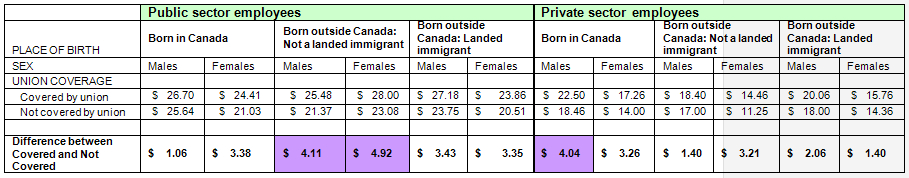

Table 4: Union Advantage by Immigrant Status, 2008

With the inclusion of the immigrant status variable in the LFS, union density and advantage can also be examined. Table 4 above looks at sector, immigrant status, gender and union coverage. Taken together, these variables show some interesting findings:

i. men and women that are not landed immigrants experience the greatest wage advantage by being unionized in the public sector (men $4.11 and women $4.92)

ii. the wage advantage experienced by men and women in the public sector that are landed immigrants are still considerable compared to Canadian-born men in this sector and their counterparts in the private sector

iii. Canadian-born men have the lowest wage benefit than the other groups in the public sector, but they have the highest in the private sector

DEMONSTRATION 2

The union advantage beyond the wage

Unionization is associated with formalized and equitable pay and promotion structures as well as layoff rules which tend to minimize some of the most overt forms of discrimination on the basis of gender and race, and many unions have consciously tried to promote pay and employment equity for their lower paid and women members through bargaining. In practice, unionized workers are also most likely to benefit from legislated pay and employment equity laws than are non union workers because unions have the resources to make these laws effective (Jackson 2004: 9).

Unionized workers are also more likely to have full-time jobs, access to health and pension benefits, more control over their work, opportunities for training, and some degree of job security through their collective agreements. Jackson (2004) emphasizes that “the most important benefit of unionization for a worker is a formal contract of employment which can be readily enforced through the grievance and arbitration process.”

The union advantage around wages has not been won without struggle with employers. Some public sector unions have engaged in lengthy and bitter disputes with their employers to address pay inequities, for example, the struggle for Bell workers by the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union (CEP) (Swift 2003), and for federal government workers by the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC). A victory was finally achieved for PSAC workers in 1999 after fifteen years of bickering with the government and several court cases. This three billion dollar award affected 230,000 PSAC members and former members, the majority of whom were women who were earning less than $30,000 a year (Public Service Alliance of Canada 2002).[13] Other advantages for unionized workers, such as the impact of collective strength on workers’ experience, are harder to quantify. For example, in 1996, women workers at Suzy Shier organized two retail stores, despite threats from management. Deborah De Angelis, one of the organizers, said, “[m]y fight isn’t about money: it’s about dignity” (1998: 26). Although it took a year to negotiate a first contract, De Angelis reports that having a voice is the biggest gain: “Before, they could fire you, no problem. They had nobody to answer to. Before, if the manager didn’t like what you were saying, she just wouldn’t put you on the schedule. And if you were not on the schedule for four weeks, you were automatically terminated. That policy is now gone, thanks to the collective agreement … That is so much power”(29).

The movement of Canadian union women has organized for more than forty years inside unions to pressure unions to take up such issues as childcare, reproductive rights, sexual/racial harassment and violence against women, pay equity, and employment equity among others. As a result of such organizing, unions have now made great strides around many of these concerns, and some innovative union initiatives have now translated some of these concerns into collective bargaining language. Yet around each of these issues, union hierarchies originally questioned the legitimacy of unions addressing them. But with each victory, the boundaries of what constitutes a legitimate union issue have shifted, the understanding of what is seen to be relevant to the workplace has altered, and the support for social unionism has increased.

The following discussion highlights some of the non-wage benefits that unionized workers, especially women, have negotiated in their collective agreements.[14] For example, some Canadian Auto Worker (CAW) locals now have Women’s Advocates in the workplace trained to deal with women’s concerns around violence, harassment or any other form of discrimination;[15] and anti-discrimination and human rights training for membership, union leadership and front-line management personnel. They have also developed language for and won protection against discipline procedures for women who lose time at work as a result of an abusive family situation (Nash 1998).[16] The CAW is probably best known for its initiatives around childcare: The CAW negotiated the first Canadian private sector child care fund with American Motors in 1983. The employer agreed to pay two cents for every hour worked by every employee into a fund that was used to help employees pay fees in registered child care facilities. Since then, the CAW has expanded the fund, and operates its own child care centers. The 1999 agreement with Ford and Daimler/Chrysler includes a $10/day fee subsidy for spaces in licensed non-profit care, and the creation of a $150,000 a year fund to enhance existing licensed services by extending hours or adding infant care. Because the fund will contribute approximately $15 million to licensed non-profit centers over the course of one agreement, employers as well as members have a significant interest in the creation of a national program. In the 1999 agreement Daimler/Chrysler agreed to write a joint letter to the Prime Minister supporting the formation of a national child care program (de Wolff 2003: 51; see also Nash 1999).

In Canada, taking more control over time at work has increasingly become a union focus, especially given data which shows that 20% of Canadians worked regular weeks longer than 40 hours and only about half of those working overtime are paid (de Wolff 2003: 21; see also White 2002).[17] As de Wolff points out: “Many unions have recognized that addressing work and life issues for their members starts with negotiating reasonable workloads, limited overtime and enough flexibility in house of work for workers to handle regular but unpredictable caring obligations” (20). In “Bargaining for Work and Life” (2003), she provides sample contract language and an encouraging list of union initiatives around limiting overtime and on-call work, shortening the work week, controlling shift schedules, making schedules accommodate workers’ needs and arranging for job sharing. For example, she reports that “CEP members who are clerical workers and technicians at SaskTel have every second Friday off work, for a total of 26 days a year. A rumour that management was planning to cut back these days put the issue of time off to number one during bargaining in 2001” (23).[18] See Box 1 for examples of negotiated provisions.

Unions have also negotiated benefits that address the needs of specific equity-seeking groups to ensure recognition of differences based on social identities. For example, the protection against discipline procedures for women who lose time at work as a result of an abusive family situation bargained by the CAW acknowledges the pervasive domestic violence women face. The United Steel Workers of America (USWA) agreement with Anvil Range Mining Corporation removed work rules which prevented First Nations employees from engaging in their traditional economic activities and lifestyles, including hunting and fishing, and following religious observances, while maintaining continuing employment with the Company. CUPE 3903 has negotiated for eight weeks of Transsexual Transition leave from teaching with York University. Discussions of family benefits increasingly reject narrow and generic definitions of family that exclude gay and lesbian couples and open up understandings of who constitutes family.

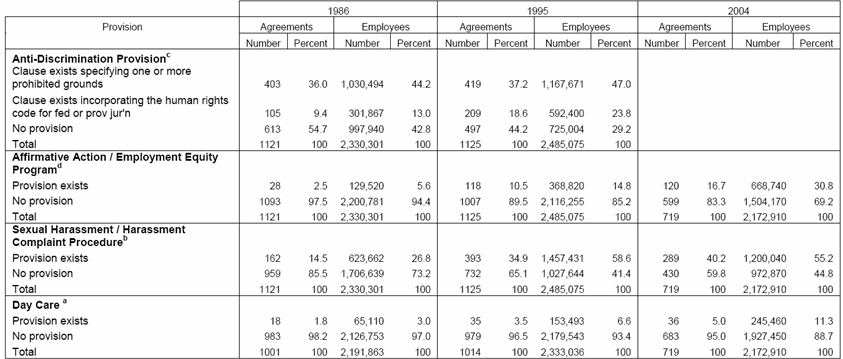

Overall, statistical data indicate significant shifts in collective bargaining coverage and support the claim for a union advantage beyond the wage premium. In 1986, Human Resources and Social Development Canada (HRSDC) began analysing collective agreement provisions. Table 5: Selected Collective Agreement Provisions, 1986, 1995, 2004 demonstrates increasing coverage of key gendered issues. For example, in 1986 only 2.5 percent of agreements (covering 5.6 percent of employees) had affirmative action provisions; by 1995 this had increased to almost 11 percent of agreements (covering 14.8 percent of employees); in 2004 16.7 percent of agreements has such provisions (covering 30.8 percent of employees). Table 5 also shows significant shifts in the areas of harassment, daycare and anti-discrimination clauses.[19]

Table 5: Selected Collective Agreement Provisions, 1986, 1995, 2004

Significantly, in 1998, HRSDC substantially changed its coding procedures to reflect the addition of many new issues on collective bargaining agendas. The list of provisions now include expanded items around family-related issues (such as childcare, eldercare, family leave and responsibilities, and maternity, paternity and parental/partner leaves), and in coverage for lesbian, gay, bi-sexual and transgendered workers.[20] It is noteworthy that over 15 percent of agreements now offer paid leave for family responsibilities and 21 percent of agreements specifically extend paid and unpaid family leave to those in same sex partnerships.[21]

Undoubtedly the feminization of the union membership has supported the shift toward gendering the collective bargaining agenda. In fact, in 2004, for the first time, the unionization rate for women was slightly higher than for men: 31 % for women and 30% for men; by 2002 women were half of all union members in Canada (Morissette, Schellenberg and Johnson 2005: 5). In response to their female-dominated membership, the public sector unions have pushed demands for maternity leave, flexible work hours, and anti-discrimination provisions in collective bargaining. They have “negotiated significant improvements in wages and working conditions. Special attention was paid to correction of long-standing salary anomalies in lower-paid, largely female-dominated job classifications” (Peirce 2003: 259-60). Kumar (1993: 223) also points to the different equity-related areas taken up by the public and private sector unions. He concludes that “the relatively greater success of unions in the public sector and in larger bargaining units appears to be related to different employer attitudes, the higher percentage of women in the public sector, and the significantly greater bargaining strength of the unions.”

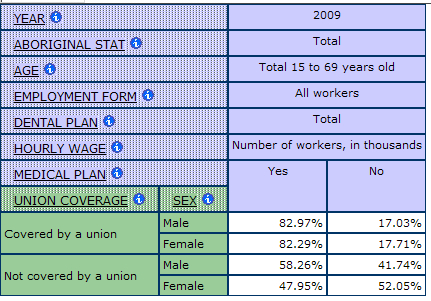

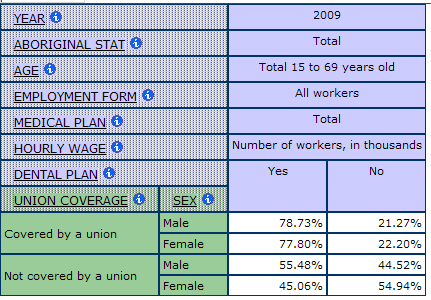

Demonstrating fully that these benefits correspond to unionization would require comparing the situation of unionized and non-unionized workers. Jackson (2004: 6) points out that “the impact of unions on pensions and benefits is even greater than on wages, particularly in smaller firms. Union members in Canada are about three times more likely to be covered by an employer-sponsored pension plan than non-union workers, and twice as likely to be covered by a medical or dental plan. Establishment and improvement of benefits package is usually a key union bargaining priority, and an apparent erosion of the union wage premium in the 1990s is probably explained by the growing costs of non wage benefits to employers.” Some tables available on the GWD, for example, in the precarious employment and health care modules, include a benefits dimension along with union coverage and other dimensions of interest such as migration status (PE GSS9 A-1, A-2, and A-3). Benefits covered include retirement and pension plans (PE GSS9 P-3 and A-1; PE SLID E-1; HC SLID A-3), parental leave (PE GSS9 A-2), paid sick leave (PE SWA P-23), and medical/dental plans (PE SLID E-2 and UN SLID C-1). Users may locate these tables by searching for “benefits” in either the library or the statistical tables section. An example of a table comparing the provision of medical and dental benefits by union coverage and sex is shown in Tables 6a & 6b. These data highlight the significance of the union advantage for benefits beyond wages.

Tables 6a &6b: Medical and Dental Benefits by Union Coverage and Sex, Canada, 2009

*Rows may not sum to 100% due to rounding and a very small “don’t know” category.

In a UK study, Bewley and Fernie (2003) consider the success of unions in negotiating policies of benefit to women and compare the profile to non-unionized workplaces. Their results are unequivocal: workplaces with union recognition were almost twice as likely to have a formal written policy on equality of treatment; twice as likely to collect statistics on career progression; four times as likely to monitor promotions by gender; and three times as likely to review selection procedures to identify indirect discrimination. They were also more likely to provide flexible working and help with childcare.

Equity audits of collective agreements Undoubtedly in many collective agreements, issues of concern to equity-seeking groups are absent; in others, apparent neutrality masks commonsense biases (for more on equity bargaining, see Briskin 2006a). To address these problems, many unions subject their collective agreements to an “Equity Audit” (See Audits and Model Clauses below). Audit documents provide lists against which agreements can be assessed, and model clauses on a wide variety of equity issues. They also offer a snapshot view of the union advantage.[22] Audits can also be done by provincial labour federations and central labour organizations in order to share best practices and develop joint and centralized campaigns which can strengthen the bargaining power of individual unions, and thereby address the needs of equity-seeking groups more effectively. In this regard, the Trades Union Congress (TUC), the parallel UK organization to the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), passed an historic motion in 2001 to change its constitution: a commitment to equality is now a condition of TUC affiliation and each affiliate commits itself to eliminating discrimination within its own structures and through all its activities, including its own employment practices.[23] This constitutional change was accompanied by a comprehensive TUC equality auditing process on a bi-annual basis to maximize the dissemination and adoption of best practices throughout the trade union movement. The second audit released in 2005 focuses primarily on equality bargaining.[24]

The 2005 Audit showed that the key equality bargaining priorities in the TUC affiliates are measures to achieve equal pay, particularly for women; work-life balance and flexible working; parental rights; and race discrimination and equality issues. The Audit identifies policies, guidelines and briefing materials from member unions on these issues and reports in detail on bargaining achievements and offers contract language in the following areas: flexible working and work-life balance; parents and careers; women’s pay; black, minority ethnic and migrant workers; lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender workers; religion and belief; age; health and safety; union learning and education; harassment and bullying; recruitment, training and career progression; monitoring of the workforce.

The focus of the 2009 Equality Audit was on bargaining for equality at work. It found that:

“A large proportion of unions (63 per cent) have issued materials to negotiators on women’s pay and employment, which was also cited as the clear top equalities bargaining priority for unions over the last two years. However, fewer than a third of unions (30 per cent) say they have achieved bargaining success with employers in this area. … Flexible working and work/life balance is … an area where a relatively high amount has been achieved through collective bargaining, with 44 per cent of unions saying they have achieved results on this topic. The area where most unions report that they have actually struck deals with employers since 2005 is working parents, parents-to-be and carers. Just over half of all unions (51 per cent) have been successful in this area. An indication of unions’ acceptance to take on an ever-widening range of equalities issues is provided by the fact that more than one in three unions have issued negotiating guidance or policy on issues around trans workers, and the same proportion have done so in the area of migrant workers. Indeed almost a quarter of unions have achieved negotiating successes for migrant workers’ equality in areas such as provision of time off for English language training, recognition of foreign qualifications, prevention of unreasonable deductions from wages and recognition agreements with agencies supplying migrant workers”.[25]

The information in the TUC Equality Audits is collected through an extensive survey. For each audit, the form is included as an Appendix and could easily be adapted to the Canadian context.

Undoubtedly monitoring the implementation of equity provisions is of critical importance. The International Labour Organization (ILO) (Lim, Ameratunga and Whelton 2002: 33) comments that “Unless there is proper implementation and monitoring, the gains achieved may be only on paper.” The data is instructive: “Of those with collective agreements, about 60 per cent of the unions, 44 per cent of the IUF affiliates and about 40 percent of the national centres reported that they systematically monitor the implementation of collective bargaining provisions on gender equality.” However, a research project on equal opportunities and collective bargaining in the European Union found that “Where agreements with good equality potential had been concluded, the research found that the social partners were often less concerned with their implementation and monitoring. Thus, the full potential of the agreements was not always realised” (Bleijenbergh, de Bruijn and Dickens 2001: 10).

NEGOTIATING WORKING TIME

Overtime Should Be Voluntary, Not Mandatory

“Management agrees that overtime work shall be kept to a minimum. It is further agreed that overtime work shall be voluntary and that no employee shall be compelled to work overtime or shall be discriminated against for refusal to work overtime.” (UFCW Local 175 and Mitchell’s Gourmet Foods, 1998 – 2003).

No Overtime When Members are On Lay-Off

“In the event that there are employees on layoff status, the Company shall first call laid off employees capable of performing the work for any available work that would otherwise be worked as overtime, unless other arrangements are agreed to.” (CEP Local 63-0 and AvestaPolarit).

Split Shifts

“The Company may assign split [shifts] but only after having discussed the assignment with the union. A split [shift] shall be interpreted as one covering more than nine consecutive hours. For each one hour between work periods on a split [shift], one half (1/2) hours wages shall be paid.” (International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 435 and NITS Communications, 1999 – 2002).

Schedule Accommodation

“An employee returning from maternity leave may be exempt from standby and callback until the child is one year old provided that other qualified employees in her area are available.” (Newfoundland Association of Public Employees and Government of Newfoundland, 1998 – 2001).

Prepaid Leave

“The Prepaid Leave Plan is plan developed … to afford all employees the opportunity to take a six month or one year leave of absence and to finance the leave through deferral of salary in an appropriate amount from the previous years…. The following shall constitute the deferral make-up of the plan. i) two years of one-quarter of annual salary in each year followed by six months leave; ii) four years of one fifth of annual salary in each year followed by one year of leave.” This agreement maintains employees’ seniority and benefit levels at regular salary level while in the plan and ensures that employees can return to the same job. (Office and Professional Employees International Union, Local 343, and Ontario Federation of Labour, 2002-2004). Examples from de Wolff, 2003: 22-26.

AUDITS AND MODEL CLAUSES

“Bargaining Equality: A Workplace For All” from CUPE (2004) is a comprehensive binder of information which opens with the union’s equality statement and an introduction on how to make equality issues a priority in bargaining. The sections discuss a broad range of equality issues and include a discussion of the issue, tools for self-auditing and sample collective bargaining language.

“The Issues and Guidelines for Gender Equality Bargaining“, Booklet 3 of Promoting Gender Equality: A Resource Kit for Unions from the ILO (Lim, Ameratunga and Whelton 2002) offers a very comprehensive list of issues for bargaining equality organized under five categories: ending discrimination and promoting equal opportunities, wages and benefits, family-friendly policies, hours of work, and health and safety. For each issue, there is an explanation, checklists for working with and thinking about the issue, text from relevant ILO documents, and examples from many countries.

WORKS CITED

Abella, R. (1984). Equality in Employment: A Royal Commission Report. Ottawa: Canadian Government Publishing Centre. Aidt, T. and Tzannatos, Z. (2002). Unions and Collective Bargaining: Economic Effects in a Global Environment. Washington: The World Bank.

Anderson, J., Beaton, J. and Laxer, K. (2006). “The Union Dimension: Mitigating Precarious Employment?” In Leah F. Vosko (Ed.), Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada. (pp. 301-317). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Archibald, K. (1970). Sex and the Public Service. Ottawa: Ministry of Supply and Services. Baines, D. (2010). “Neoliberal Restructuring, Activism/Participation, and Social Unionism in the Nonprofit Social Services.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(1), 10-28.

Bairstow, S. (2007). “There isn’t Supposed to be a Speaker Against! Investigating Tensions of ‘Safe Space’ and Intra-Group Diversity for Trade Union Lesbian and Gay Organization.” Gender, Work and Organization, 14(5), 393-408.

Bezanson, K. (2006). “The Neo-Liberal State and Social Reproduction: Gender and Household Insecurity in the Late 1990s.” In Kate Bezanson and Meg Luxton (Eds.), Social Reproduction: Feminist Political Economy Challenges Neoliberalism. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Bewley, H. and Fernie, S. (2003). “What do Unions do for Women?” In Howard Gospel and Stephen Wood (Eds.), Representing Workers: Trade Union Recognition and Membership in Britain. (pp. 92-118). New York: Routledge.

Bleijenbergh, I., de Bruijn, J. and Dickens, L. (2001). Strengthening and Mainstreaming Equal Opportunities through Collective Bargaining. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement in Living and Working Conditions.

Bonacich, E., Alimahomed, S., and Wilson, J. (2008). “The Racialization of Global Labor.” American Behavioral Scientist, 52(3), 342-355.

Botswana Federation of Trade Unions and International Confederation of Free Trade Unions. (1991). Joint BFTU/ICFTU Panafrican Conference on Democracy, Development and the Defence of Human and Trade Union Rights, Gabarone, 9-11 July 1991. International Confederation of Free Trade Unions.

Briskin, L. (1999). “Unions and Women’s Organizing in Canada and Sweden.” In Linda Briskin and Mona Eliasson (Eds.), Women’s Organizing and Public Policy in Canada and Sweden. (pp. 147-183). Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Briskin, L. (2006a). Equity Bargaining/Bargaining Equity. Centre for Research on Work and Society, York University, 124. http://www.yorku.ca/lbriskin/pdf/bargaininpaperFINAL3secure.pdf