Complaints and Enforcement

COMPLAINTS AND ENFORCEMENT

Contents

This module provides researchers with information on employment standards related to complaints and enforcement. It explores the current limitations in data collection to examine how employees’ complaints and employment standards enforcement varies by jurisdiction and by employees’ social location. Two key research questions guide this module:

- What actions do workers commonly take within and beyond employment standards complaints systems when they believe their ES have been violated?

- How are employment standards complaints related to social location (e.g., social relations of gender, race/ethnicity, migration status, age, ability), social context (i.e., occupation and industry), and job characteristics? And how can the measurement of employment standards related to complaint and enforcement, defined broadly, be operationalized?

This module is comprised of an introduction to the ESD’s organizing themes and concepts surrounding complaints and enforcement, as well as a description of the indicators devised on the basis of legislative details governing employee complaints and employment standards enforcement in the jurisdictions covered by the ESD. The module also includes statistical tables incorporating survey data, a searchable library of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources, and a thesaurus of terms. These elements seek to provide a package of conceptual tools and guidelines for research.

KEY CONCEPTS

Complaints

Worker-initiated complaints are the foundation of most regimes for enforcing employment and labour rights. Complaint-driven enforcement systems typically involve an established process for handing and adjudicating complaints. In certain jurisdictions, labour inspectorates are obliged to investigate all complaints that fall under the jurisdiction of employment standards legislation. However, in other jurisdictions, inspectorates may select which complaints they will investigate. Inspectorates typically investigate complaints to determine if an employment standards violation occurred, and if so, what if any money is owed to the complainant. Penalties may be imposed on the employer. Complaints may be considered a reactive enforcement system since they rely on employees to bring forward complaints of alleged violations.

Complaint-driven enforcement suffers from numerous problems. First, there may be risks to taking action that impose barriers to employees accessing the claims process. Workers may fear reprisal if they make a claim against their current employer, notwithstanding that reprisal is unlawful. They may not be aware of their rights and thus may not know that their rights have been violated, a situation exacerbated when entitlements are not universal but rather are subject to various exemptions and qualifications. These barriers may not be evenly distributed across the labour market and this uneven distribution can lead to a second problem with complaint-based enforcement: the source and type of complaints may not be aligned with the underlying problems in the labour market. For example, workers in one sector may complain about violations more frequently than workers in another notwithstanding that violations may be more prevalent in the latter, but have become normalized as working conditions (Weil & Pyles, 2005). Similarly, employees may make disproportionately fewer complaints about violations of a particular standard compared to others, perhaps reflecting the greater difficulty they might experience in determining whether they are entitled to that particular right. Complaint-driven enforcement models also present limited opportunities for enforcement to achieve systemic effects by adopting strategies that may involve using leverage to influence the top of supply chains, rather than continually responding to complaints being voiced at the bottom (Weil, 2008, 2010).

Compliance and/or Deterrence Measures

Compliance refers to a set of strategies, including the provision of information, persuasion, and negotiation that seek to generate observance of the law. In a compliance framework, when employment standards violations are detected, voluntary compliance is encouraged through the use of strategies such as facilitating settlements or issuing orders that require the violator to do that which he or she should have done in the first place. Strategies oriented to compliance emphasize encouraging voluntary adherence to the law or, achieving adherence after the fact, rather than detecting and punishing wrongdoing (Gunningham, 2010). Compliance strategies are generally based on the view that most employers do not intentionally violate the law but rather do so out of incompetence or ignorance and therefore are not deserving of punishment. These approaches are also features of new governance paradigms (Vosko, Grundy, & Thomas, 2016) based on the premise that engaging employers in cooperative relationships with regulatory officials will lead to joint problem solving that may even produce outcomes that go beyond compliance. In theory, a compliance emphasis avoids the promotion of adversarial relations that may impede the achievement of better adherence to the law (Johnstone & Sarre, 2004; Gunningham, 2015). Compliance measures used in employment standards enforcement typically include public outreach and education and, when violations are detected, remedies which are oriented exclusively towards restoring the employee to the position they would have held had the employer adhered to the law.

Deterrence refers to the detection and punishment of wrongdoing. Theorists identify two types of deterrence: specific and general. Specific deterrence refers to the idea that regulated entities that have been subject to legal punishment will take measures to refrain from the illegal activity in the future (Gunningham, 2010). The punishment of wrongdoing can also have a “general deterrence” effect, whereby it may discourage others from choosing to engage in illegal activities. The concept of general deterrence thus captures the broader effects that flow from the punishment of individual actors. Both types of deterrence are premised on the existence of rational, self-interested actors, who conduct themselves according to a cost-benefit analysis of the consequences of their actions; they calculate the risk of being detected and punished against the benefits gained from violating the law. Deterrence strategies may also discourage incompetent or inadvertent violators by drawing their attention to the consequences of being in violation of the law and thus encouraging them to better inform themselves of and manage their obligations in order to avoid penalties. In either case, for deterrence measures to be effective, there must be a substantial risk that law-breaking will be detected and that non-trivial punishments will follow. Deterrence measures that are typically available to labour inspectorates include fines, prosecutions, and various measures to publicize employers who have violated employment standards.

Employment standards Violations, Evasion, and Erosion

A growing body of literature illustrates how new ways of organizing work are undermining employment standards and the normative goals of social minima and fairness, especially at the lower end of the labour market where competition intensifies pressure to lower labour costs. Researchers identify numerous ways in which employers seek to reduce labour costs by circumventing employment standards (Bernhardt et al., 2009). The most obvious way in which employment standards are undermined is through outright violation, which involves a direct contravention of a labour standard, such as non-payment of wages. But, in addition to direct violations, circumvention of employment standards entails a series of linked processes involving the evasion and erosion of legislative standards in addition to formal violations.

Evasion involves the adoption by employers of “strategies to evade core workplace laws” (Bernhardt et al., 2009, p. 6). Evasion may take the form of measures to misclassify employees as independent contractors so that they are not covered by the terms and conditions of employment standards. Employee misclassification is recognized as a pervasive and serious problem in many jurisdictions. For example, in the United States, recent studies estimate that between 10% and 20% of employers misclassify at least one of their employees as an independent contractor, and that misclassification is likely increasing (Carré, 2015; Donahue, Lamare, & Kotler, 2007; Smith, Bensman, & Marvy, 2012). Misclassification imposes costs on workers by depriving them of access to workplace standards. It also makes the playing field uneven, which in turn may encourage more employers to abandon standard employment relationships and avoid or evade employment standards in order to remain competitive. Yet misclassification is not just a problem for employment standards. Misclassified employees may be deprived of other employment-related benefits, such as workers’ compensation or employment insurance. As well, misclassification deprives governments of payroll and income taxes that should be paid. Indeed, studies of the United States estimate that these losses in government revenue are in the billions of dollars, and thus efforts to detect and remedy misclassification have been increased (AFL-CIO, 2016; US Treasury, 2013). Although evasion practices such as employee misclassification may not be an ES violation narrowly defined, they represent instances in which employment standards are evaded, as workers are deprived of the protections of employment standards.

Erosion entails the weakening of normative goals (e.g., social minima, universality, and fairness) and regulatory impact of employment standards. Erosion of employment standards signals an important shift in employers’ and employees’ perceptions of minimum standards for work. For example, erosion is most likely to occur where violations and evasion have become normalized, such as work environments where practices such as ‘working off the clock’ (i.e., starting work early or staying late without pay) have become standard. Erosion also involves situations where workers are conditioned to accept working conditions which fall below legally established minima, and no longer see employment standards as relevant to their situation.

Employment standards violation, evasion and erosion are interrelated and often mutually reinforcing. Continued workplace violations and evasion of employment standards can result in their erosion. However, broader political, economic, and social processes can promote the erosion of workplace norms and objectives surrounding employment standards, which not only weaken protective laws, but facilitate conditions conducive to evasion and violation. These processes are well documented in Canada, the US, Europe, Australia and elsewhere (Bernhardt et al., 2009; Emmenegger et al., 2012; Fudge, McCrystal, & Sankaran, 2012; Gautié & Schmitt, 2010; Kalleberg, 2011; Sargeant & Tucker, 2009; Tucker, 2006; Vosko et al., 2020; Weil, 2017). Considering how the erosion of norms and objectives intersects with processes of social differentiation (e.g., on the basis of sex/gender, citizenship/migration status, age, etc.) is critical to understanding how workers are deprived of protection.

Table 1: Definitions and Examples of ES Violation, Evasion, Erosion

|

Definition |

Example | |

|

Violation |

Outright violations of laws governing the employment relationship (Bernhardt et al., 2008). |

Not paying wages. |

|

Evasion |

Strategies to evade core workplace laws by creating distance between employer and employee (Bernhardt et al., 2008). |

Misclassification of employees as independent contractors. Misclassifying employees as managers to avoid paying overtime pay. |

|

Erosion |

Strategies that erode normative standards. |

Expectations that employees put in unpaid work before or after a shift. |

Given the prevalence of employment standards violations, evasion and erosion across many jurisdictions, workers’ advocates, especially worker centres and other organizations representing workers in precarious employment are demanding strengthened enforcement of employment standards as a matter of justice and they are having some success. New forms of workers’ agency are contributing to some innovative policy experimentation on the part of governments, resulting in forward-looking models of enforcement, and opportunities for policy learning about what works in employment standards enforcement (Vosko, Grundy, & Thomas, 2016).

INDICATORS

Complaint and enforcement indicators can be grouped into three main areas: “Ways of Taking Action,” “Risks of Taking Action,” and “Outcomes of Taking Action”. The goal of these measures is to capture whether survey respondents take action when they encounter employment standards violations in their workplace and the consequences of those actions. This module also includes detailed information on jurisdictional regulation and policies about complaints, the claim-making process and anti-retaliation/reprisal provisions. Overall, these indicators can help to understand the employment standards complaints and enforcement across different jurisdictions in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

First, four variables examine the types of action taken by respondents when they experience employment standards problems (CE1G1, CE2G1, CE2G2, CE2G3). These variables capture advice-seeking, including whether respondents sought advice regarding an employment standards complaint and the source of advice they sought. Sources of advice include co-workers, supervisors or managers, community organizations, complaints officers or organizations, and government or legal employees or agencies.

Another four variables classify actions taken to resolve employment standards problems (CE3G1, CE4G1, CE4G2, CE4G3). These variables capture whether any actions were taken and whether respondents made complaints. Types of actions taken to solve complaints include: discussed with family/colleague/co-worker; complained to boss/supervisor/manager; filed a complaint with employer; filed a complaint with representative; filed a complaint with union/workers association; filed a complaint with the government; or, took legal action.

Twelve variables capture respondents’ types of complaints (CE5G1-CE5G8, CE6G1, CE7G1, CE7G2, CE7G3), including whether or not respondents have complaints related to pay (owed wages, overtime pay, holiday pay, vacation pay, late pay, etc.), hours (includes being asked to work extra hours, not getting your entitled breaks, etc.), leaves (includes vacation leave, parental leave, sick leave, etc.), discrimination, health and safety, and harassment and bullying.

Second, six variables investigate the risk of taking action (CE8G1-CE8G5, CE9G1). These variables consider respondents who have chosen not to take action about an employment standards complaint and their reasons why: too costly; not confident in the system; not treated fairly; would affect employment (current and/or future); not sure what to do; treatment by other coworkers; length of time to proceed; and not worth it.

Third, two variables explore the outcomes of the employment standards complaint process for respondents (CE10G1, CE11G1). The first asks respondents if they have experienced problems at work as a result of taking action. Finally, respondents are asked if they are satisfied with the outcome of the employment standards complaint.

Detailed information on regulations in different jurisdictions in this module provides guidance for understanding the national contexts of employment standards compliance and enforcement.

Jurisdictional Mapping Information

The Employment Standards Complaint Process

CANADA

The Labour Program of the Federal Ministry of Labour handles and investigates complaints of alleged violations of Part III of the Canada Labour Code (CLC). They do not accept complaints from unionized employees covered by collective agreements who are expected to handle complaints through their union. A complaint must be filed within six months of the violation.

Employees are encouraged to approach their employer to resolve the issue before filing a complaint with the Labour Program. They are also encouraged to attempt to come to a settlement even after filing a complaint, at any time during the investigation.

Based on the Labour Program inspector’s determination of whether the complainant and their employer fall under the jurisdiction of the CLC, and whether a violation of labour standards has occurred, a Preliminary Letter of Determination is sent to both parties with the inspector’s findings. If either disagrees with the findings, they may provide additional information to the inspector. This new information is reviewed before a final determination on the complaint is made. If a violation is found to have occurred, a Letter of Determination is sent to the employer requesting that the violation be corrected. If, on the other hand, the employer is found to be in compliance with the CLC, the employee is notified of the inspector’s findings in writing. S/he may also subsequently be issued a Notice of Unfounded Complaint, advising them that the employer is in compliance, including reasons why, and that the inspector’s decision can be appealed.

If a complainant disagrees with a Notice of Unfounded Complaint, they may request a review of the inspector’s decision. This request must be made to the Minister of Labour, with written reasons and within 15 days after the notice was served. The employer also has the right to request a review of a Letter of Determination or Payment Order if their request is made to the Minister, with written reasons, payment in full (for a Payment Order) and within 15 days after the order was served. A Labour Program official will assess the review request and inform the parties whether the inspector’s decision is confirmed, varied, or overturned. Following a review, if the parties disagree and there is a question of law or jurisdiction, the case may be appealed to a referee.

At the discretion of the Labour Program, depending on the complexity of the issues, some cases may be referred directly to a referee to be heard. The referee may confirm, vary, or overturn, in whole or in part, the Notice of Unfounded Complaint or Payment Order originally issued by the inspector. The referee may also award costs in the proceedings. If a party involved in the hearing fails to comply with the referee’s decision, a request may be made to the Minister to file the referee’s order in the Federal Court of Canada. Once the order is registered in this Court, the Labour Program will no longer be involved in the case.

ONTARIO

The Ministry of Labour administers the Employment Standards Act (ESA) and its regulations and is responsible for its enforcement. It handles and investigates ESA complaints. Employees are encouraged to attempt to resolve ESA complaints directly with their employer, although the Ministry’s website recognizes that they may not feel able to do so if:

- they have already tried to contact their employer;

- the workplace has closed down;

- the employer has gone bankrupt;

- they are afraid to do so;

- the issue does not involve money;

- they are working as a live-in caregiver;

- they have difficulty communicating in the language spoken by their employer;

- they are a young worker;

- they have a disability that prevents or makes it difficult to contact their employer; or

- the reason is related to a ground under the Ontario Human Rights Code.

If for these or other reasons, an employee is unable to resolve the matter directly with their employer, or if they attempted to do so and failed, in order to access the complaints system under the ESA, the employee must file a complaint with the Ministry of Labour. This process entails filling out a form that details the alleged violation(s), collecting supporting documents when possible, and submitting the material online or by mail.

Employees must generally file a complaint within two years of the contravention in order for the claim to be investigated by the Ministry of Labour. It may be possible to make a complaint that would otherwise be outside the applicable time limit if an employee had been told by the employer that they did not have an entitlement when the employer knew or could have taken steps to find out that the employee in fact did have an entitlement; and the employer’s untrue statement was the cause of the employee’s delay in filing their claim.

Once a claim is submitted, a Claims Processor verifies that the necessary information is provided and refers it to a manager for a decision if it appears that it does not fall under the jurisdiction of the ESA. Claims that fall under ESA jurisdiction are then forwarded to an Early Resolution Officer who determines if there are grounds for an investigation. If so, the claim is forwarded to an Employment Standards Officer, who can investigate a claim based on written materials, by phone, by visiting the employer’s premises, or by calling a meeting between the parties. On the basis of this investigation, the Employment Standards Officer determines whether or not the complaint is valid, in whole or in part, and if applicable, the amount of money owed to the complainant. An Employment Standards Officer can also assess entitlements that go beyond what was claimed in the original complaint (Grundy et al., 2017; Vosko et al., 2020, Chapters 2 & 5).

If an employer is unwilling or unable to comply with either an Early Resolution Officer’s or an Employment Standards Officer’s decision, the officer can issue an order to pay wages, a compliance order, a ticket, a notice of contravention or, for certain violations, an order to reinstate, and/or compensate an employee (these are described more fully in the section on Recovering Monetary Entitlements).

Special Situations

There are a few situations in which an employee who is covered by the ESA cannot file a claim with the Ministry of Labour:

- Employees represented by a trade union generally cannot file a claim under the ESA. If employees are covered by a collective agreement, regardless of whether or not they are actually members of the union, they must use the grievance procedure contained in the collective agreement between the employer and the trade union

- Employees cannot file a claim with the Ministry of Labour for a failure to pay wages or benefits if the employee has already started a court action against the employer for the same matter

- Employees who have started a court action for wrongful dismissal cannot file a claim for termination or severance pay under the ESA with respect to the same termination/severance of employment.

Employees who have filed a complaint with the Ministry of Labour for unpaid wages, benefits, or termination or severance pay must withdraw the claim within two weeks of the date of filing it if they intend to start a court action with respect to those unpaid wages, benefits, or alleged wrongful dismissal.

These restrictions on pursuing a claim through both the courts and the Ministry of Labour do not apply to claims for compensation or reinstatement, for example, where a claim is filed for a violation of the pregnancy, parental, emergency, family medical leave, or reprisal provisions of the ESA.

UNITED KINGDOM

In the United Kingdom, employment standards complaints are processed by the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service and/or through an Employment Tribunal. In either case, complainants must inform the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service of their intention to make a complaint against their employer, and it generally must be submitted within three months of the infraction.

The Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service must first offer early conciliation, which is a voluntary process; neither complainants nor employers are required to participate. If there is interest from both parties, the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service conciliator will talk over the phone with the complainant and the employer separately. The conciliator may request an in-person meeting between the parties. If agreement is reached within Early Conciliation, the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service conciliator drafts an Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service settlement form (COT3), which is a legally binding enforceable contract.

If the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service cannot contact one of the parties, one of the parties is not interested in early conciliation, or the conciliator believes that no agreement can be reached through early conciliation, then the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service will issue an Early Conciliation Certificate. The unique identifier from this certificate must be submitted with an Employment Tribunal claim. The timeline for submission to the employment tribunal pauses while the complaint is in Early Conciliation; it restarts once the Early Conciliation Certificate is issued.

If the complainant chooses to proceed to the Employment Tribunal, they must submit a claim form (ET1) to both the Advisory, Conciliation, and Arbitration Service and their employer. The Tribunal is comprised of three members: a legally qualified Employment Judge and two lay members. Potential outcomes of the tribunal include: employee compensation, employer reimbursement of employee tribunal fees, changes to working conditions, and employee reinstatement.

AUSTRALIA

In Australia, employment standards complaints are processed by the Fair Work Ombudsman and/or in small claims court.

The Fair Work Ombudsman offers voluntary mediation services; neither party is required to participate. The Fair Work Ombudsman does not play an advocacy role in mediation. Instead, the mediator’s role is to facilitate an agreement, and the mediator does not provide legal advice or advocacy for either party. The mediation is a conference call of up to two hours in length between the mediator and both parties. The mediator may also speak with the parties individually. If an agreement is reached through mediation, the parties have the option of signing a Terms of Settlement, which is a legally binding agreement.

Complainants also have the option of making a claim within small claims court, if the claim is for less than $20,000 and it is within the statutory period (usually within 6 years of the infraction). Complainants must pay a fee to file their claim; fees vary between courts. Complainants can request to have the fee waived if it is a financial hardship.

A Compliance Notice is a legally enforceable written notice issued by a Fair Work Inspector to an employer identifying actions they must take to address breaches of the Fair Work Act. The notice must detail how the employer breached workplace law, what they must do to address the issue, and the time within which they must address the issue.

An Enforceable Undertaking is a court-enforceable promise made by the employer to address the breach that is agreed to by the regulator. The employer must “admit the contravention, which must be described in detail in the Enforceable Undertaking; agree to remedy the contravention(s) in the manner specified (for example, through payment(s) to rectify underpayment) and identify the timeframe within which the contravention will be remedied (unless the contravention(s) have already been rectified); and specify any other actions which the employer agrees to undertake and the timeframe within which those actions will be taken.” Enforceable Undertakings may contain commitments for improving compliance in the future, which may include, but are not limited to, participation in FWO educational programmes, the training of managers and staff, and the completion of audits and compliance plans, as well as the adaptation of work organization systems.

UNITED STATES

Employees who believe they have experienced a violation of the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) can make a complaint with the Wage and Hour Division of the US Department of Labor. That is, if an employee has not been paid at least the minimum wage, or has not been paid at a premium rate for overtime that they have worked, they can make a complaint. The Wage and Hour Division can only accept complaints when employers have violated the FLSA; other concerns in which this law is not explicitly broken are not applicable.

Violations of the FLSA are subject to a 2-year statute of limitations, which means that complaints must be registered within two years of the offense. The statute of limitations is extended to three years in cases where a “willful violation” has occurred.

All complaints made to the Wage and Hour Division are confidential. The only times at which a complainant’s identity could be revealed is if it is required in order to pursue the allegation and the complainant consents, or if the Wage and Hour Division is required to submit the information in court.

If a complaint against an employer is received by the Wage and Hour Division, an investigation may follow. Investigations of workplaces occur as a result of complaints but may also be initiated by the Wage and Hour Division. Employers are not advised of the reason for the investigation. In addition, third parties may also file complaints with the Wage and Hour Division on behalf of others.

CALIFORNIA

Employees in California can make complaints against employers for unpaid wages (including overtime, vacation pay and other forms of unpaid wages, unauthorized deductions from pay, and failure to provide meal and rest periods in accordance with state law. Normally, claims must be made within three years of the violation.

Complaints are made to the Department of Industrial Relations Division of Labor Standards Enforcement. Complex complaints involving large numbers of employees and records may be handled through the Division’s Bureau of Field Enforcement. The claims process begins when a claimant visits a local office of the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement with appropriate documentation. Within 30 days of filing the claim, the claimant will be informed of the next steps, which will be one of:

- Referral to a conference

- Referral to a hearing

- Dismissal of the claim

In many cases, the claim is resolved informally between the employer and employee before a conference or hearing occurs. The purpose of a conference, if it is recommended, is to resolve the claim without going to a hearing. In the conference, no one is under oath or required to prove their case, and witnesses do not attend. It is an informal proceeding, unlike a hearing.

If the claim is not resolved in a conference, or if it is directly referred to a hearing, then the formal proceeding begins. This is effectively a legal proceeding, the results of which may be later appealed.

ILLINOIS

If an employee is owed wages (including contractually agreed-upon vacation pay, commission, or bonuses), they may file a claim with the Illinois Department of Labor. The complaint must be filed within one year of the infraction.

Once a complaint has been filed, reviewed, and accepted, the Department will notify the employer and allow for the employer to respond. An investigation will be conducted and, if there is sufficient evidence that an infraction occurred, a hearing will be scheduled. At the hearing, both sides are entitled to have an attorney present.

The results of the hearing will normally be available within 90 days. There is an appeals process that can be triggered, but only within 15 days of the judgment.

NEW YORK

In New York State, employees may make an unpaid wage claim to the Department of Labor for

- unpaid regular wages;

- unauthorized deductions from pay;

- payment of less than the minimum wage; or

- unpaid overtime.

The claim must be filed within three years of the alleged wage violation. Employees cannot file unpaid wage claims if they are also utilizing small claims court. In cases where an employer has agreed to provide vacation, holiday, or sick pay, bonuses, pay for expenses, or reimbursement for medical bills but has not done so, an “unpaid wage supplement” claim form can be submitted.

Anti-Retaliation/Reprisal Provisions

CANADA

Part III of the Canada Labour Code (CLC) prohibits unjust dismissal. Unjust dismissal occurs when an employer terminates an employee’s contract of employment, and in doing so, breaches a term of the contract of employment or an employment law. Provisions of the CLC identify who is entitled to protection from unjust dismissal as well as the steps employees are advised to take should they feel that they have been unjustly dismissed. Constructive dismissal is also considered unjust dismissal under provisions of Part III of the CLC. Constructive dismissal requires an employer to be non-compliant with an employee’s contract of employment, or significantly alter the terms of employment, thereby prompting or encouraging the employee to resign as opposed to accept the new conditions of employment. In any case, if an employee believes that their termination of employment lacks legitimate justification, they have the right to file an unjust dismissal complaint with any Labour Program office.

Once an employee files a complaint against a dismissal they deem to be unjust, an inspector will be assigned to the case to assist the parties involved to negotiate and reach a settlement that all parties accept. This is the stage at which the majority of unjust dismissal cases are resolved. However, should the inspector be unsuccessful, the dismissed employee may request the assignment of an adjudicator to the case. Prior to the appointment of an adjudicator, the Minister of Labour will decide whether the case is deserving of one. The adjudicator acts as the mediator in this situation. They are given the responsibility of making a decision to which all parties are bound. The decision of an adjudicator cannot be appealed. Under particular and exceptional circumstances, the decision may be submitted for review by the Federal Court of Canada. When dismissals are legally deemed unjust, the adjudicator has a wide spectrum of avenues that they may pursue in providing a remedy or solution.

A July 2016 Supreme Court of Canada ruling in Wilson vs Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd. may be seen as putting in place anti-reprisal measures. The 6-3 ruling was delivered in a case filed by a supervisor at Atomic Energy, a Crown corporation, who was fired without any explicit reason and given a generous severance package. The supervisor claimed that his 2009 firing was in reprisal for blowing the whistle on corrupt procurement practices at Atomic Energy. Atomic Energy argued that giving notice or severance meant it did not have to provide cause for the dismissal (Montague-Reinholdt, 2016). The ruling was based on the court’s interpretation of the CLC provisions giving employees under its jurisdiction the right to complain to an adjudicator if they feel they have been unjustly dismissed. The court majority argued that in the 1,740 cases since these provisions became law in 1978, adjudicators had ruled in all but 18 cases that employers could not dismiss employees without cause. This, they argued, was the reasonable reading of the law’s intent. The Court found that the “unjust dismissal” provisions of Part III of the CLC prohibit “without cause” dismissal of non-managerial, non-unionized employees with at least 12 months of consecutive service, thereby allowing those employees to access the remedial relief (reasons, reinstatement, equitable relief) available under the Code (Montague-Reinholdt, 2016).

ONTARIO

Anti-reprisal measures are contained in Section 74 of the Employment Standards Act (ESA). Employers are prohibited from penalizing or threatening to penalize employees in any way for:

- asking the employer to comply with ESA regulations;

- asking questions about rights under the ESA;

- filing a complaint under the ESA;

- exercising or trying to exercise a right under the ESA;

- giving information to an employment standards officer;

- taking, planning on taking, being eligible or becoming eligible for a pregnancy, parental, personal emergency, family caregiver, family medical, critically ill child care, organ donor, reservist or crime-related child death or disappearance leave;

- being subject to a garnishment order (i.e., a court order to have a certain amount deducted from wages to satisfy a debt);

- participating in a proceeding under the ESA; or

- participating in a proceeding under section 4 of the Retail Business Holidays Act (regarding tourism exemptions that allow retail businesses to open on holidays).

An employer who does penalize an employee for any of these reasons, by dismissing or threatening to dismiss the employee, for instance, can be ordered by an employment standards officer to reinstate the employee to their job and/or compensate the employee for losses incurred because of the employment standards violation.

UNITED KINGDOM

Section 94 of the Employment Rights Act provides employees with a right not to be unfairly dismissed. Section 104 of the Act deems as automatically unfair any dismissal resulting from the assertion of numerous statutory rights, including those established in the National Minimum Wage Act; Working Time Regulations; Part-Time Workers Regulations, Fixed-Term Employee Regulations, and the Transnational Information and Consultation of Employees Regulations. If unfair dismissal is established by an Employment Tribunal, the Tribunal can order reinstatement, re-engagement or compensation.

AUSTRALIA

Employees are protected from unlawful termination, which includes termination for making or planning to make a complaint. They must make an unlawful termination application within 21 days of the termination. The Fair Work Commission then holds a conference to resolve the conflict. If the conflict is not resolved, the parties can agree to using arbitration to resolve the dispute. Potential outcomes of arbitration include reinstatement of the employee and/or payment to the employee. If the parties don’t agree to arbitration, the employee can then make an application to the Federal Court.

UNITED STATES

Employers are prohibited from retaliating against employees who make claims to the Department of Labor. According to the Wage and Hour Division, “if adverse action is taken against an employee for engaging in protected activity, the affected employee or the Secretary of Labor may file suit for relief, including reinstatement to his/her job, payment of lost wages, and damages.”

CALIFORNIA

California law prohibits employers from retaliating against employees who seek to enforce workplace rights (State of California, Labor Commissioner’s Office 2016b). Employees cannot be fired, demoted, suspended, or disciplined for filing a claim. This applies to all workers, including those with insecure immigration status. Laws passed in 2013 explicitly prevent employers from retaliating by reporting, or threatening to report, an employee’s citizenship or immigration status. The law states that employers may have their business licenses revoked if they engage in such practices, moreover, they may be found guilty of criminal extortion.

If an employee believes that their employer has retaliated against them for making a claim to the Department of Industrial Relations, they can file a retaliation complaint with the Department of Labor Standards Enforcement. In most cases, the complaint must be filed within 6 months of the retaliation incident. In order to file a retaliation complaint, detailed information about the incident must be submitted to the Unit, including witness statements.

The complaint to the Department must include information on the complainant’s preferred remedies for the retaliation incident. Possibilities vary depending on the nature of the retaliation, but remedies may include: payment for lost wages; reinstatement of a former position; adjustments to personnel files; penalties; or agreeing not to retaliate again in future.

Once a retaliation complaint has been filed, it will be investigated by the Department, and a conference or hearing will be scheduled. A deputy of the Department will then make a determination in the case, which both sides have the opportunity to appeal.

ILLINOIS

It is illegal under Illinois law for an employer to retaliate against an employee who files a claim with the Department of Labor for unpaid wages. If the employer is found guilty of retaliation, they are guilty of a Class C misdemeanour. Employees may file their retaliation claim with the Department of Labor directly, or in civil court.

NEW YORK

It is illegal under New York State law for an employer to retaliate against an employee who has filed a claim with the Department of Labor. Employers found guilty of retaliation can be fined from $1,000 to $20,000. They may also be required to repay any wages owing and liquidated damages as ordered. Employees must file their claim with the New York Department of Labor within three years of the alleged violation.

Employees have the option to file a civil case against their employer, instead of relying on the Department of Labor’s processes. This must be filed within two years of the retaliation incident.

Recovering Monetary Entitlements

CANADA

If a monetary complaint is founded, the inspector attempts to have the employer voluntarily pay the wages or other amounts owing before issuing a payment order.

If the employer refuses to pay amounts owed, the inspector will issue a Payment Order to either the employer or the directors of the corporation for the payment. A Payment Order to recover wages will cover 12 months before the complaint, and an order to recover vacation pay will cover 24 months before the complaint.

When wage recovery from a corporation is impossible or unlikely, directors may be held liable for amounts due to an employee or employees during their incumbency. Corporate directors are jointly and individually liable for employees’ wages and other amounts to which the employees are entitled, such as severance and notice pay, up to a limit equivalent to six months’ wages.

A claim against a debtor of an employer, up to the amount stated in the payment order, may also be issued by a Labour Program inspector. The debtor would be required to pay the amount to the Minister within 15 days. The issuance of a written order to a debtor may also be made by a Regional Director of the Department.

A payment order issued by an inspector or confirmed by a reviewer may be registered in the Federal Court of Canada system if a party to the order makes such a request to the Minister. Following court proceedings, the payment order could be upheld as a court judgment. Once an order has been filed in the Federal Court, the statutory authority of the Labour Program ends and the Labour Program no longer has the authority to enforce the order.

ONTARIO

There are several avenues for wage recovery in Ontario. First, even after a claim has been filed with the Ministry and an Employment Standards Officer becomes involved, the employer may settle, with or without facilitation by the Employment Standards Officer. Vosko, Noack, and Tucker (2016, p. 69) have found that the use of settlements is increasing, and that settlements, especially those that are facilitated, appear to result in less favourable outcomes for employees compared to complaints assessed by an Employment Standards Officer, assuming that all else is equal.

If a complaint is not settled (and not withdrawn) and an Employment Standards Officer has determined that an employee has experienced an employment standards violation and has a monetary entitlement, the employer may voluntarily comply with the Employment Standards Officer’s finding. Voluntary compliance is achieved in about half of complaints with a monetary entitlement (Vosko, Noack, & Tucker 2016, p. 56).

If voluntary compliance is not achieved, the Employment Standards Officer will normally issue an Order to Pay Wages or an Order to Compensate and/or Reinstate. An Order to Pay Wages can be issued against an employer, a Director, or a related employer. Orders to Compensate and/or Reinstate are issued to employers to achieve restitution in specific circumstances. Where wage orders remain unpaid, the order can be filed with a court and have the same status as a court order (Employment Standards Act, 2000, s. 126; Vosko et al., 2020).

If an employer or client of a temporary help agency does not apply for a review within 30 days of the date the Order was served, it is final and binding. If the employer or client of a temporary help agency has not paid the required amount, the Director of Employment Standards forwards the order or notice to a collector (Vosko et al., 2020). Although collections were privatized for many years, recently they have come to be carried out by a collections unit in the Ministry of Finance (Vosko, Noack, & Tucker 2016, p. 70). The Director may authorize the collector to collect a reasonable fee and/or costs from the employer or client of a temporary help agency. The fees and costs are added to the amount of the order.

A substantial amount of the monies owed to employees are from employers who are insolvent or bankrupt. In these cases, recovery of unpaid wages is difficult because workers become one of several creditors owed money and are paid subject to priority ranking as determined by federal bankruptcy and insolvency legislation (Vosko, Noack, & Tucker 2016, p. 75). The Ministry of Labour may assist employees by filing Proofs of Claim with the Trustee in Bankruptcy or the Monitor.

UNITED KINGDOM

In most cases where monetary entitlements are due, they are to be paid by the employer to the complainant. If a claim is resolved through Early Conciliation, both parties sign an ACAS settlement form (COT3), which is a legally binding document. If the employer agrees to pay a monetary entitlement to the complainant and fails to do so, the complainant can take action through the civil courts to compel the employer to pay.

If a complaint is resolved through an Employment Tribunal, the tribunal can order the employer to pay the complainant compensation (including tribunal fees). If the employer does not make the payment, the complainant must first contact them to remind them of their obligation. If they continue to not make the payment, the complainant can contact the court to enforce payment. Complainants from England or Wales can use the Fast Track scheme, which sends a High Court Enforcement Officer to demand payment from the employer. There is a fee of £60 for this service, which is recoverable once the employer makes their payment. Complainants from Scotland can request that the court send a sheriff officer to demand payment from the employer. If the employer is insolvent, complainants can be compensated by the government for certain types of claims. Further, when a business becomes insolvent, employees are treated as preferential creditors.

AUSTRALIA

Monetary entitlements are to be paid by the employer to the complainant. If the claim is resolved through Fair Work Ombudsman mediation, both parties may sign a Terms of Settlement. If the employer agrees to pay a monetary entitlement to the complainant and fails to do so, the complainant can make a claim in small claims court.

If the claim is resolved through small claims court, the court can order the employer to make a payment to the complainant. If they do not, the court can seize property, force bankruptcy, or wind up the company to ensure payment is made to the complainant.

If the employer is insolvent, complainants can be compensated by the government for certain types of claims.

UNITED STATES

The Department of Labor has the authority to recover unpaid wages and liquidated damages that are owed to employees. The Department also has the authority to assess and recover civil money penalties that must be paid to the government.

The recovery of unpaid wages or damages is done administratively whenever possible. The Department of Labor is authorized to “supervise” these payments to the claimant(s). In more extreme cases, or cases where this administrative process has been unsuccessful, the Department of Labor may proceed with litigation in a number of ways by filing a lawsuit on behalf of the affected employees. If an employee chooses to file a private suit against the employer, the Department will not do so on their behalf.

CALIFORNIA

If a claimant has won their case, that is, if a hearing has occurred and the hearing officer has judged in favour of the employee, they are entitled to back pay for any unpaid wages. The employer is then required to pay the employee. In these cases, it is left to the claimants themselves to collect the pay that is owed to them. These are often cases where the employer has shown a strong unwillingness to pay wages, since they have refused to settle throughout the entire hearing process. In these situations, claimants are unlikely to recover their unpaid wages: a study found that between 2008 and 2011, only about 17 percent of employees who had been awarded a judgment were actually able to recover any pay at all (Cho, Koonse, & Mischel, 2013, p. 13).

Claimants whose employers have not paid may voluntarily proceed in obtaining a business property lien in order to collect the payment. A claimant may also obtain a writ of execution along with a business property lien in order to seize the employer’s assets. If at this stage the employer has not paid the assessed back wages, the claimant should determine the businesses owned by the employer and then proceed to obtain the employer’s assets through a levy. The Labor Commissioner’s Office “Judgement Enforcement Unit” provides guidance to successful claimants attempting to recover their wages.

ILLINOIS

If an employee’s complaint results in their favour, the employer is required to pay the amount that has been judged owing. If the employer fails to comply with the order to pay in a timely manner, they are penalized as follows:

- 20 percent of the total judgment, payable to the Department of Labor;

- 1 percent per day delayed, payable to the employee

According to Illinois state law, the Department is authorized to “assist any employee… in the collection of wages.”

NEW YORK

The New York State Labor Commissioner will help employees who have filed an unpaid wage claim with the New York Department of Labor to recover their unpaid wages. If an employer has been found guilty of wage theft by the Labor Standards Division of the Department of Labor, the Labour Commissioner is authorized to do the following:

- institute criminal proceedings against the employer;

- impose interest or civil penalties on the employer;

- take an assignment of the employee’s wage claim; or

- institute a civil suit to recover unpaid wages.

However, according to a 2015 study, even when a judgment has been made and the claimant has gone through legal proceedings, it is rare that the full balance is repaid (Urban Justice Center, et al., 2015).

Deterrence Penalties for Employment Standards Violations

CANADA

The Labour Program emphasizes voluntary compliance with the Part III of the Canadian Labour Code (CLC) by supplying information and tools to help employers and employees understand and apply federal labour standards, although it also enforces compliance through proactive workplace inspections and investigating complaints of labour standards violations.

When a violation is found, the employer will be asked to correct the violation and/or implement appropriate workplace practices. The employer has the opportunity to provide an Assurance of Voluntary Compliance. This is a written commitment that the violation will be corrected within a specified period of time.

If a violation of the CLC is not corrected despite the efforts of the Labour Program, prosecution in a court of law may be taken. Criminal prosecution may be pursued whenever someone who knows the legal obligations willfully breaks the law. Repeated violations are taken as an indication of intentional actions. An offence is determined a repeat offence if the first offence occurred within the preceding five years.

Upon summary conviction, a corporation that has violated federal labour standards will be fined:

- up to $50,000 for the first offence;

- up to $100,000 for the second offence; and

- up to $250,000 for the third (and any subsequent) offences.

An employer that is not a corporation will be fined:

- up to $10,000 for the first offence;

- up to $20,000 for the second offence; and

- up to $50,000 for the third (and any subsequent) offence.

Upon summary conviction of a serious offence of Part III of the CLC, an employer will be fined up to $250,000 for the first (and any subsequent) offences. A serious offence includes failure by an employer to: offer workers’ compensation coverage; insure any long-term disability plans they may offer to employees; and comply with group termination requirements.

The fine for an employer’s failure to keep or make records available to Labour Program inspectors is $1,000 per day that the violation continues. The fine for failing to comply with an order to pay wages or to reinstate an employee is also $1,000 per day that the violation continues.

ONTARIO

There are 3 types of penalty available under the ESA. These are Notices of Contravention, Certificates of Offence (tickets or summonses) issued under Part I of the Provincial Offences Act, and prosecution under Part III of the Provincial Offences Act.

There is a fundamental legal difference between the Notices of Contravention, and Part I tickets/summonses and Part III prosecutions. Notices of Contravention are administrative monetary penalties, while tickets/summonses and Part III prosecutions are regulatory offences. Administrative penalties are generally considered to be a more flexible mechanism for enforcing compliance insofar as they can be imposed without judicial involvement and do not have to comply with the stricter procedural requirements that regulatory offences attract. Moreover, administrative penalties, including their size and the procedures for imposing them, can be addressed entirely in enabling legislation (in this case the ESA) and do not require amendments to the POA or new or revised regulations. Because administrative penalties can be imposed without a conviction and a formal finding of guilt, they might be perceived as having a lesser deterrent effect; however, that depends on whether an employer who receives a Notice of Contravention perceives it differently than one who is issued a ticket or summons (Vosko, Noack, & Tucker, 2016, p. 50).

Notices of Contravention: If an employer has contravened the poster requirements of the ESA or has failed to keep proper payroll records or to keep these records readily available for inspection by an Employment Standards Officer, an officer can serve a notice of contravention with the following prescribed penalties:

- $250.00 for a first contravention

- $500.00 for a second contravention in a three-year period

- $1,000.00 for a third contravention in a three-year period

If an employer is found in contravention of any other provision of the ESA, the penalties prescribed are:

- $250.00 for a first contravention multiplied by the number of employees affected

- $500.00 for a second contravention in a 3-year period multiplied by the number of employees affected

- $1,000.00 for a third contravention in a 3-year period multiplied by the number of employees affected.

A person who is served with a Notice of Contravention can apply to the Ontario Labour Relations Board for a review within 30 days.

Vosko, Noack, and Tucker (2016, p. 52) found that Employment Standards Officers rarely issue Notices of Contravention. Over a 6-year period from 2009-10 to 2014-15, there were almost 46,000 complaints which detected a violation: in about half of those cases (48 percent), the employer did not voluntarily comply, but in only 392 instances, or 1 percent of all complaints with violations, were Notices of Contravention issued. Although Notices of Contravention are used somewhat more frequently when violations are detected via workplace inspections than when they are detected investigating an individual complaint, the incidence is still extremely low.

Tickets: A notice of offence (commonly called a “ticket”) can be issued under Part I of the Provincial Offences Act (POA).

Tickets carry set fines of $295, with a victim fine surcharge of $60 and an administrative fee of $5, for a total of $360 plus court costs. The amount of the fine is set by the Chief Justice of the Ontario Court of Justice. If issued a ticket, an employer can choose to pay the fine, or appear in a provincial court to dispute the charge set out in the ticket and is entitled to a judicial hearing at which the prosecutor has the burden of proving guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

There were no ticketable offences under the ESA until the regulation was amended in 2004 (O. Reg. 162/04); since that time Employment Standards Officers have been empowered to issue tickets when they detect violations of the listed offences. There are currently 59 ticketable ESA violations; they range across the statute and include both non-monetary violations (e.g., failure to post materials) and monetary ones (e.g., failure to pay minimum wages). Money collected from these fines goes to the municipality in which the offence occurred, while the victim fine surcharge goes into a Victims’ Justice Fund and is used to compensate the victims of crime (Vosko, Noack, & Tucker, 2016, p. 53-54).

Vosko, Noack, and Tucker (2016: 54) found that, like Notices of Contravention, tickets are infrequently issued, with about 277 issued per year, on average. Over the three years from 2012-13 to 2014-15, tickets were issued in roughly 4 percent of all cases where violations were found, and 4 percent of cases where monetary violations were found. The authors concluded, assuming that NOCs and tickets were not being issued in the same cases, adding together the number of NOCs and tickets issued each year, low-level deterrence measures were used in 5 percent of all cases with violations and 5 percent of all cases with monetary violations. They further found that about 7 percent of tickets issued were contested (based on data from 2008/09 to 2012/13 only), and the majority of these resulted in convictions (the remainder were primarily withdrawn or dismissed).

Prosecutions: Employers can also be penalised for a regulatory offence through a prosecution under Part III of the Provincial Offences Act. According to the Act, it is an offence for an employer or other person to:

- contravene the ESA or regulations;

- make or keep false records or other documents that must be kept under the ESA;

- provide false or misleading information under the ESA; and/or

- fail to comply with an order, direction, or other requirement under the ESA or regulations.

Part III of the Provincial Offences Act sets out the procedure to be followed for prosecutions. Unlike tickets, Employment Standards Officers do not have the power to launch the investigation required for prosecution, but rather can make a recommendation for prosecution to the Legal Services Branch of the Ministry of Labour, which initiates the process for determining whether to launch a Part III prosecution. Ultimately, it is up to the Legal Services Branch, which is part of the Ministry of the Attorney General, to determine whether or not to launch a Part III prosecution based on the strength of the evidence and whether a prosecution would be in the public interest. Defendants are entitled to a judicial trial and their guilt must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt (Vosko, Noack, and Tucker 2016: 55). If convicted, the employer or other person could be subject to a fine or a term of imprisonment or both. Individuals convicted of an offence can be fined up to $50,000, imprisoned for up to 12 months, or both. A corporation can be fined up to $100,000 for a first conviction. If the corporation has already been convicted of an offence under the ESA, it can be fined up to $250,000 for a second conviction, and up to $500,000 for a third or subsequent conviction.

Directors of corporations can also be charged if the director fails to comply with an Order to Pay Wages issued against the directors pursuant to ss.106 and 107 of the ESA. Finally, where the employer is a corporation, an officer, director, or agent of the corporation may be prosecuted for authorizing or permitting or acquiescing in the contravention.

In addition to the imposing a fine or term of imprisonment, a court can also order the convicted person or corporation to take whatever action is necessary to remedy the violation, including paying wages and compensating and/or reinstating an employee.

Vosko, Noack, and Tucker (2016, p. 56) found that Part III prosecutions are used exceedingly infrequently. Each prosecution can involve more than one defendant and more than one charge. In the 7-year period between 2008-09 and 2014-15, there were 92 businesses prosecuted for employment standards violations under the Provincial Offences Act, involving 292 charges. For the three years from 2012-13 to 2014-15, 41 prosecutions were launched, comprising roughly 0.18 percent of cases with violations detected by complaints and inspections (0.20 percent of cases with detected monetary violations). Moreover, penalties for Part III violations are relatively low compared to the legal maximums. The total value of penalties of all fines in those years was $835,926. The average fine per business was $20,388, while the average penalty per charge was $7,740. This average penalty per charge is only 15 percent of the $50,000 maximum penalty for individuals, and 8 percent of the maximum of $100,000 for corporations (for a first offence).

Vosko, Noack, and Tucker (2016, p. 57) observed that employers are rarely prosecuted for the initial violation of the Act (e.g., failing to pay wages) but rather for disobeying orders to pay or interfering with officers. That is, they are prosecuted for defying the authority of the state rather than for violating workers’ rights.

UNITED KINGDOM

If the employer does not pay the full sum due from either an Early Conciliation agreement or a tribunal award within 28 days, a financial penalty will be imposed, to be paid to the Secretary of State. The penalty will be equivalent to 50 percent of the original award (minimum £100, maximum £5000). If the employer pays the original award and the financial penalty within 14 days of the notice of the financial penalty, the penalty will be reduced by 50 percent.

Some types of employment are protected by additional agencies, such as the Employment Agency Standards Inspectorate and the Gangmasters & Labour Abuse Authority. If these agencies find violations of employment standards they can prevent an individual or corporation from operating those types of employment, and launch criminal proceedings.

AUSTRALIA

There are four enforcement outcomes in response to breaches of the Fair Work Act: infringement notice, compliance notice, enforceable undertaking, and litigation.

An Infringement Notice is a fine that is given for a breach of record-keeping or pay slip requirements. They are issued by Fair Work Inspectors and can be issued any time an employer breaches these requirements. Fines are a maximum of $540 for an individual or $2,700 for a corporation. Payment must be made within 28 days of the fine; if an employer does not pay, they may face litigation.

Employers who do not comply with a Compliance Notice may face fines of a maximum of $5,400 for an individual or $27,000 for a corporation.

Enforceable Undertakings can stipulate that, should the wrongdoer fail to comply with the voluntary EU, the FWO may make an application to the court for orders against that person. Furthermore, with an EU, the wrongdoer is to publish a public notice declaring the contraventions and remedial actions to take place.

Litigation is reserved for the most serious breaches of the Fair Work Act.

UNITED STATES

There are several ways that the Department of Labor can penalize employers who violate the Fair Labour Standards Act (FLSA):

- Employers may be required to provide back pay for those wages and associated damages;

- Civil monetary penalties for violations may be applied. The maximum penalty for repeated or wilful violations of minimum wage and overtime rules was $1,925 in 2019;

- An injunction may be sought to restrain future violations of the law;

- A US District Court Order may be sought to prevent the shipment of affected goods; and/or

- Criminal penalties, such as fines and imprisonment, may be applied in cases where employers have wilfully violated the FLSA.

Multiple factors are considered when the fine is assessed: the size of the business; the seriousness of the violation; any efforts made by the employer to comply with the FLSA; the employer’s explanation for the violations; the employer’s history of violations; the employer’s commitment to future compliance; the interval between violations; the number of employees impacted; and, whether there is any pattern to the violations.

CALIFORNIA

The penalties for violations of employment standards vary depending on the violation. In most cases, penalties are monetary. The penalties for violations are found in the California Labor Code. Some examples of specified penalties are:

- Employers who misclassify employees as independent contractors may be fined anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000 for each violation, and these fines may increase up to $25,000 if the employer has displayed a pattern of misclassification.

- Employers who fail to pay timely and accurate wages are subject to a $100 fine for the first violation and $200 for each subsequent violation. They are also responsible for all legal costs.

ILLINOIS

An employer who has been found guilty of not paying wages in full must repay the employee those wages in addition to 2 percent damages for each month in which underpayment occurred. The employer must also pay an administrative fee to the Department of Labor, in accordance with the following schedule:

- $250 when the amount owing is below $3000;

- $500 when the amount owing is more than $3000 and less than $10,000; and,

- $1000 when the amount owing is $10,000 or more.

There are also additional penalties if ordered payments are not made in a timely manner, as follows:

- 20 percent of the total judgment, payable to the Department of Labor;

- 1 percent per day delayed, payable to the employee.

NEW YORK

New York State employers found guilty of labor code violations can be penalized according to the following schedule:

- $1,000 for the first violation;

- $2,000 for the second violation;

- $3,000 for the third and subsequent violations.

Demonstration

Filing Complaints

Research on employment standards compliance across jurisdictions demonstrates that there is often a considerable “enforcement gap” between workers’ minimum employment rights and their experience of illegal violations at work (Vosko et al, 2020). Furthermore, the likelihood of both experiencing an employment standards violation and of taking formal action to resolve it (i.e. filing a complaint with a government entity such as a Ministry of Labour) are shaped by factors such as gender, racialization, employment type, immigration status and occupation/industry.

The following demonstration illustrates how researchers can use the Employment Standards Database to answer questions related to employment standards compliance, particularly issues related to workers’ complaints, within and between surveys. The demonstration explores complaints and other actions workers take when experiencing a problem at work through the use of the statistical tables drawn from the surveys. For example, we compare the actions of male and female respondents who experience a problem at work. We then explore variations by whether a union is present in the workplace and by industry/occupation to better understand the circumstances shaping whether workers file complaints or take other action to enforce their rights at work. As we learned in this module, deterrence penalties and other enforcement mechanisms vary by jurisdiction. In many instances, workers face considerable uncertainty when filing complaints or otherwise seeking redress for workplace violations. These risks are heightened by social inequalities related to gender, racialization, immigration status, and occupational segregation.

Note that this demonstration assumes that you are familiar with the basics of manipulating tables. If you are unsure how to choose which variables to display, remove variables or items from tables, modify the table layout, calculate percentages, etc., please see our tutorial on using the statistics database and/or review the demonstrations for other modules.

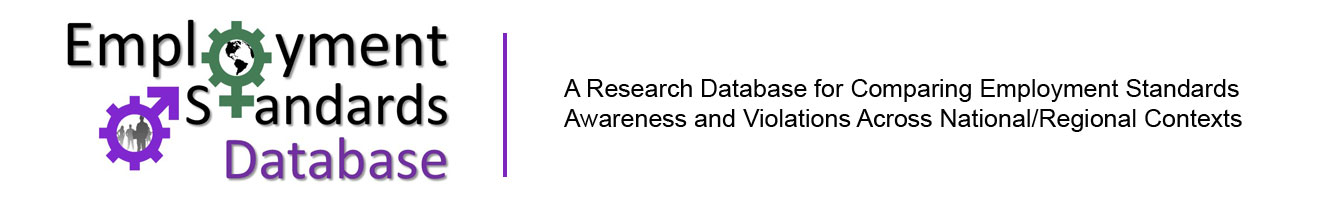

Using data from the SESC, SWPA and BLUW surveys, Table 1 compares whether respondents took action after experiencing a potential violation at work by gender. (For readability, in this table and the other tables in this demonstration, we have filtered out respondents who did not answer the question and those who reported not experiencing a problem at work.) As Table 1 shows, men were more likely to take action after a problem at work. Among male respondents, 89.5% reported that they took some action, while the figure for female respondents was 84.9%. We must recall, however, that the ‘Further Action’ variable in this module can include a myriad of potential avenues for recourse, including such minor actions as speaking with a supervisor. The number of avenues available may explain why the percentage of workers taking action after a problem at work appears quite high. We know from the academic literature on precarious employment and employment standards enforcement that many common workplace violations, such as unpaid wages, holiday, vacation and overtime pay, go unreported, i.e. many workers do not file formal complaints with Ministries of Labour or other relevant government bodies (Weil & Pyles, 2005; Vosko et al., 2020).

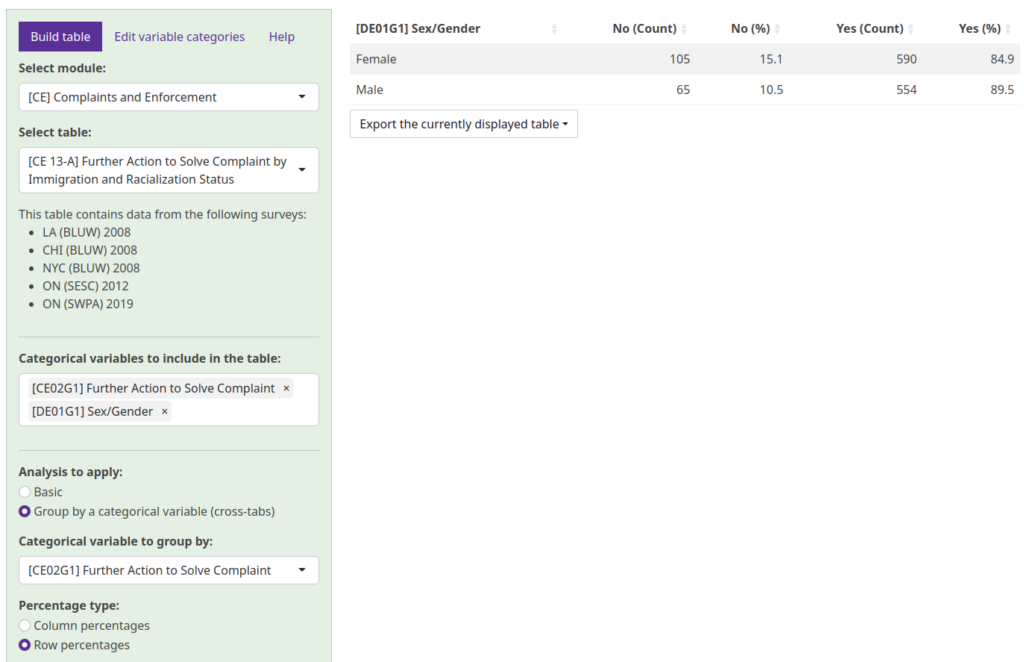

Perhaps the single most important factor shaping whether workers are able to enforce their rights at work is the presence of a union in the workplace. In Canada, for example, the roughly 30% of workers who are union members will have a collective bargaining agreement which outlines their rights and the employer’s duties in the workplace, while also providing rules for when and how the employer may discipline and dismiss employees. Unionized workers will also have access to a grievance procedure system through which to make complaints when the employer has violated provisions of the collective agreement. In some cases, unionized workers may file employment standards complaints with a Ministry of Labour, or the equivalent government entity in another jurisdiction, but these cases are rare because of the grievance mechanisms available through collective agreements. However, there are also instances in which a union is present in the workplace but is not the bargaining agent for all workers employed or working there. The data covered in Table 2, which draws from the IAER, UWS, EAER and BLUW surveys, does not distinguish which workers/respondents are represented by unions. We do, however, get a sense of the impact of union presence in the workplace when it comes to workers’ response to employment standards violations or other problems at work. (The reason the figures are so different from Table 1, with fewer respondents having taken action, is that the table contains data from different surveys from Table 1 — this highlights the importance of making note of which surveys are included in a given table. In a more in-depth analysis, the SURVEY variable, available in all tables, can be added to your table to make this more transparent.)

As the data show, where a union is present, a slightly higher percentage of respondents took further action after experiencing a problem at work. Where a union was present and recognized as the bargaining agent, 32.2% of respondents took further action after experiencing a problem at work. Where a union was present but not the recognized bargaining agent for workers, 40% of workers took further action (note that this represents a small part of the sample — just 15 respondents in this category reported experiencing a problem at work). Where no union was present in the workplace, only 22.9% of respondents took further action.

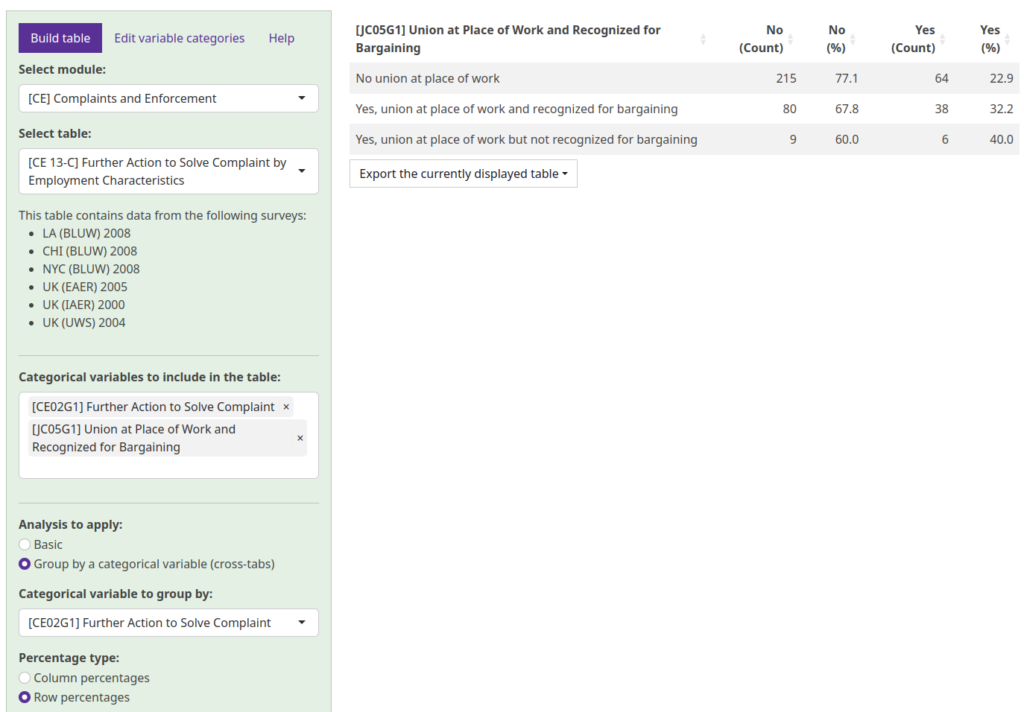

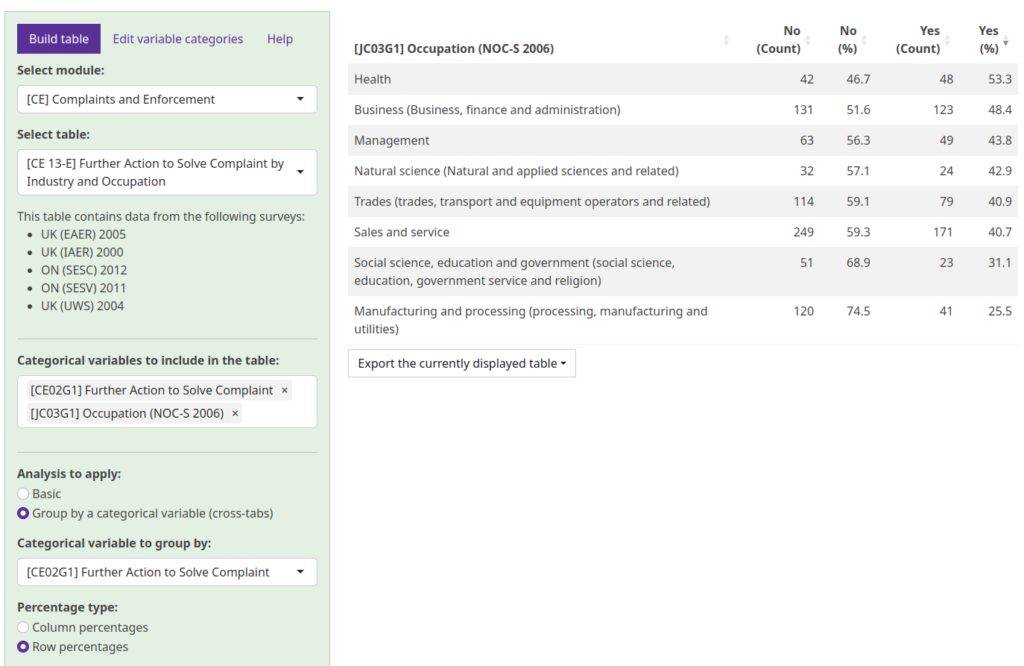

In this module, we can also explore how industry or occupation shape whether workers take action when experiencing a potential employment standards violation at work. Employment standards violations are unevenly distributed across sectors and industries. Workplaces characterized by low wages, for example, often have higher instances of ES violations. Moreover, workers in industries or occupations characterized by precarious employment will often face greater challenges when attempting to enforce their employment standards rights, whether through filing a formal complaint or taking some other action. Table 3a, which contains data from IAER, UWS, EAER, SESC and SESV, first looks at whether workers took action by industry, using the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS). Looking at this table, we can see that, among respondents, taking action after experiencing a problem at work is uneven across industries. For example, only 35.1% of respondents working in manufacturing took further action, while 48.0% of those in management and administration took further action.

Table 3b then approaches this same question by occupation, by comparing whether respondents took further action by National Occupational Classification (NOC). As with the previous table, we see unevenness across occupations when it comes to respondents taking action after experiencing potential employment standards violations at work. The table is sorted from highest to lowest rate of taking action, and we have removed two categories with very low cell counts. As shown in the table, the three occupations with the highest rates of taking action on violations are health (53.3%), business (48.4%) and management (43.8%), while the three lowest are manufacturing/processing (25.5%), social science, education and government (31.1%), and sales/service (40.7%).

Keep in mind, however, that “taking action” encompasses a wide range of responses to potential employment standards violations in this dataset. Research demonstrates that service sector workplaces, for example in retail trade and hospitality, have a disproportionately high incidence of employment standards violations (Bernhardt et al., 2009; Gautié & Schmitt; 2010; Weil, 2008). Workers in these industries often experience precarious working conditions characterized by low wages and a lack of certainty over regular working hours and continued employment. These factors can contribute to fear of reporting a workplace violation.

Researchers can further explore issues related to complaints and enforcement by searching terms such as “complaints,” “compliance,” deterrence” and “enforcement” in the thesaurus and library resources, and by reviewing other secondary literature cited in this module. To read more about how to use all of the databases, please see the following tutorials:

Works Cited

AFL-CIO (2016). Misclassification of Employees as Independent Contractors. Washington, DC: Department of Professional Employees, AFL-CIO. Retrieved from https://dpeaflcio.org/programs-publications/issue-fact-sheets/misclassification-of-employees-as-independent-contractors/

Bernhardt, A., et al. (2009). Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers: Violations of Employment and Labor Laws in America’s Cities. New York, NY: National Employment Law Project.

Carré, F. (2015). “(In)dependent Contractor Misclassification.” EPI Briefing Paper, 403. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.epi.org/files/pdf/87595.pdf

Cho, E. H., Koonse, T., & Mischel, A. (2013). Hollow Victories: The Crisis in Collecting Unpaid Wages for California’s Workers. New York, NY & Los Angeles, CA: National Employment Law Center & UCLA Labor Center. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qg631b6

Donahue, L. H., Lamare, J. R., & Kotler, F. B. (2007). The Cost of Worker Misclassification in New York State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, School of Industrial and Labor Relations. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1009&context=reports

Emmenegger, P., Häusermann, S., Palier, B., & Seeleib-Kaiser, M., Eds. (2012). The Age of Dualization: The Changing Face of Inequality in Deindustrializing Societies. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Fudge, J., McCrystal, S., & Sankaran, K., Eds. (2012). Challenging the Legal Boundaries of Work Regulation. Oxford, UK: Hart.

Gautié, J., & Schmitt, J., Eds. (2010). Low-Wage Work in the Wealthy World. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Grundy, J., Noack, A. N., Vosko, L. F., Casey, R., & Hi, R. (2017). “Enforcement of Ontario’s Employment Standards Act: The Impact of Reforms.” Canadian Public Policy, 43(3), 190-201.

Gunningham, N. (2010). “Enforcement and Compliance Strategies.” In R. Baldwin, M. Cave, & M. Lodge (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Regulation (pp. 120-145). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gunningham, N. (2015). “Compliance, Deterrence and Beyond.” In M. Faure (Ed.), Elgar Encyclopaedia of Environmental Law (pp. 63-73). London, UK: Edward Elgar.

Johnstone, R., & Sarre, R. (2004). “Regulation: Enforcement and Compliance.” Research and Public Policy Series, 57. Australian Institute of Criminology.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.