Job Uncertainty

JOB UNCERTAINTY

Contents

This module provides researchers with information on employment standards related to the issue of uncertain job duration. It explores whether, and if so, the degree to which, permanent or temporary forms of employment affect employees’ entitlements to employment standards, with particular emphasis on protections extended to employees experiencing termination or severance of employment. Two key research questions guide this module:

- What are the central features of permanent and temporary employment and how do these features differ across the national and sub-national jurisdictions? How does termination/severance protection in employment standards relate to other features of job un/certainty, and how do they differ across the national and sub-national jurisdictions?

- How are the features of employment duration and termination/severance coverage related to employees’ social location (e.g., social relations of gender, race/ethnicity, migration status, age, ability), social context (i.e., occupation and industry), and job characteristics?

This module is comprised of an introduction to the ESD’s organizing themes and concepts surrounding job un/certainty, as well as a description of the indicators devised on the basis of legislative details governing uncertain job duration in the jurisdictions covered by the ESD. The module also includes statistical tables incorporating survey data, a searchable library of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources, and a thesaurus of terms. These elements seek to provide a package of conceptual tools and guidelines for research.

KEY CONCEPTS

Permanent and Temporary Employment

Permanent Employment: Permanent employment refers to an open-ended, ongoing employment relationship and is a key pillar of the standard employment relationship (see introduction). Permanent employees tend to benefit from predictable working conditions, such as regular hours and wages, and often have access to employer-provided benefits and entitlements, as well as leave provisions. They are likely to be covered by most basic employment standards governing minimum wages, hours of work, leaves, and to be eligible for a range of statutory protections and social benefits (e.g., unemployment insurance).

Open-ended employment relationships reached their greatest prevalence in the decades following World War II, a period of sustained employment growth, when product markets were characterized by high levels of demand. The open-ended employment relationship was sustained by a contract of employment between each employee and the employer, which established work rules and benefits systems. Statutory employment protections establishing penalties for unfair or arbitrary dismissal, often pegged to the duration of the employment relationship, were integral to labour standards in Canada and Australia, and, to a lesser extent, the UK, in contrast to the US.

Permanent employment is not necessarily characterized by a high degree of security, however. Employees in permanent jobs may lack control over the labour process and earn low wages. Indeed, the quality of many permanent jobs has declined along many dimensions of precariousness (see for e.g., Campbell, 2008 on Australia; Vosko, 2006 on Canada). In the US, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) entails no statutory protections against dismissal, or what is, in legal terms, called “at-will employment.” At-will employment means that any worker can be legally discharged “without notice for good reason, bad reason or no reason” (Commission for Labor Cooperation, 2003, p. 26). Union power and internal labour markets can buffer workers from at-will employment and have done so historically in the United States; however, both have declined in recent years, increasing the share of workers subject to at-will employment (Hyde, 1998; Summers, 2000). Increasing uncertainty can be measured through one of its effects: decreasing job tenure, that is, jobs held for shorter lengths of time.

Temporary Employment: Temporary employment has grown in prevalence in many jurisdictions covered by the ESD, and tends to be more precarious than permanent forms of employment. Temporary employment is uncertain by definition. As employers pursue ‘flexibility-enhancing’ labour strategies, temporary or contract employment also affords them the opportunity to reduce their labour costs by eliminating workers, without the need to provide cause for termination, or provide severance pay. Many temporary employees are also excluded from workplace benefits, such as health benefits and pension plans.

Temporary employment can be divided into four categories that often overlap: agency, fixed-term or contract, seasonal, and casual employment. The prevalence of these categories varies in different industries and jurisdictions. Temporary agency work involves a triangular employment relationship where an employment agency mediates between an employer and a worker. For most of the twentieth century, it was restricted by law in many OECD countries. Its growing prevalence is strongly associated with regulatory changes extending legitimacy to temporary help agencies (Vosko, 2000, 2010b).

Fixed-term or contract employment refers to an employment relationship with a specified end date. Increasingly, employees are given multiple, recurring temporary contracts. Although the positions they hold may have become a permanent part of the organization, these workers are required to periodically reapply for their jobs.

A third subset of temporary employment is seasonal work, where employment occurs at particular times of the year. Seasonal work is often grouped with fixed-term work. However, it has distinct features. Though formally “temporary”, seasonal workers – including many international migrants – may work for the same employer season after season in sectors such as resource extraction, agricultural production, and tourism. Seasonal employment tends to be a stable feature of particular industries and occupations. In Canada, for example, it is concentrated in the construction and resource sectors, and associated with sales and service occupations, as well as trades, transport, and equipment operations (Fuller & Vosko, 2008). The stability of seasonal employment depends on how industries employing seasonal workers are organized and, in the case of resource-based industries, environmental factors (Sinclair, MacDonald, & Neis, 2006).

In countries such as Canada and the United States, casual or on-call employment generally refers to work that is intermittent or lacking a regular schedule. The meaning of casual employment in Australia, however, is different. Rather than a definition linked to the presence or absence of a regular work schedule, casual employment in Australia functions effectively as a status in employment; there casual employment is an employment relationship where the worker lacks the full range of rights and entitlements associated with full-time paid employment (e.g., access to annual leaves) (Campbell & Burgess, 2001). Casuals in Australia may be employed intermittently, but they may also have a regular schedule. They may work on a fixed-term or on an ongoing basis, and they may also be employed through a temporary help agency. To compensate for their insecurity, casual workers receive a premium known as casual loading (Stewart, 1992; O’Donnell, 2004; Watson, 2005). Casual employment is more common than other types of temporary employment in Australia.

All of these types of temporary employment – agency, fixed term, seasonal, and casual – are by definition precarious along the dimension of certainty. The link between particular types of temporary employment and other dimensions of precarious employment varies by regulatory context and especially the dominant regulatory framework governing the employment relationship.

Job Tenure

Job tenure is related to the degree of certainty of continuing employment. Employees with short job tenure, who are often engaged in temporary agency, fixed-term, casual or on-call employment, are more likely to experience uncertainty over the duration of employment. Job tenure can also shape an employee’s access to regulatory protections. For example, many employees with short job tenure have limited access to tenure-based employment standards, such as severance pay or termination notice. In addition, many jurisdictions have statutory benefits, such as pensions or unemployment benefit systems, that require a certain minimum period of job tenure as a condition of eligibility, or that provide graduated protection based on job tenure.

Employment Standards Related to the Termination or Severance of Employment

ES that provide a degree of protection to employees facing the termination or severance of employment are a key measure shoring up the SER characterized, in part, by an open-ended employment relationship. Such standards take several forms:

Termination Notice: A number of jurisdictions require employers to provide a certain period of written notice before an employment relationship is terminated. Such notice is intended to provide employees with a limited amount of advance warning to plan for the termination. Across jurisdictions, entitlement to termination notice begins after a period of time on the job (e.g., three months in Ontario and at the federal level in Canada). Additionally, the length of notice required often depends on the employee’s length of job tenure. For example, in the UK, employers are required to give at least one week’s notice for each year an employee has worked (e.g., three years of continuous work requires three weeks’ notice), to a maximum of 12 years/weeks. Under Australia’s Fair Work Act (FWA), the corresponding maximum is four weeks for employees with more than five years’ tenure. In the US, the FLSA requires no notice of termination. Typically, no termination notice is required if an employee is terminated for willful misconduct, disobedience, or willful neglect of duty.

Termination Pay: Many jurisdictions require employers to provide termination pay when termination notice is not provided. It is usually the case that termination pay in lieu of notice is equivalent to the pay for the period that would have been worked had notice been given.

Severance Pay: Severance pay is provided to eligible employees whose employment is severed. It is intended to compensate for the loss of long-term employment and the seniority that accompanies such employment. Qualifying criteria for severance pay are more stringent than termination pay. In Ontario, for example, whereas termination notice or pay in lieu is required for most employees with more than three months’ job tenure, severance pay is available only to eligible employees who have worked for the employer for five or more years, and whose employer is of a certain minimum size measured by either number of employees or size of payroll. A closely related concept is redundancy pay, which is required in Australia and the UK when an employee is terminated because the employer no longer requires the employee. Different jurisdictions use different formula for determining the amount of severance or redundancy pay owed to employees.

Given the job tenure requirements for notice of termination/termination pay and severance pay, employees in different types of temporary employment or employees with short job tenure often do not benefit fully from these standards.

INDICATORS

Job uncertainty indicators can be grouped into three types: “Job Security”, “Job Duration”, and “Dismissal.” The purpose of these measures is to identify the degree of job uncertainty that survey respondents report; whether they are employed permanently or temporarily; and whether they have experienced dismissal from work. Overall, these indicators can be examined to better understand employment standards related termination and severance of employment policies and regulation across different jurisdictions in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

First, one variable captures whether survey respondents report they are concerned about their job security or not (JU1G1). Second, four variables measure job duration in order to capture precarious employment (JU2G1, JU2G2, JU2G3, JU3G1), including permanent/temporary employment and job tenure. Finally, two variables capture whether the respondent experienced dismissal or unfair dismissal from work (JU4G1).

Detailed information on regulations in different jurisdictions in this module provides guidance for understanding the national contexts of employment standards related to termination and severance of employment.

Jurisdictional Mapping Information

Termination Notice

CANADA

An employee who has completed at least three consecutive months of continuous employment with an employer is entitled to either:

- notice in writing, at least two weeks before a date specified in the notice, of the employer’s intention to terminate employment on that date; or

- 2 weeks’ wages at the employee’s regular rate of wages for the employee’s regular hours of work, in lieu of the notice.

In workplaces where a collective agreement exists that allows an employee whose position is being made redundant to displace another employee on the basis of seniority, the employer must:

- give at least two weeks’ notice in writing to the trade union that is a party to the collective agreement and to the employee that the position of the employee has become redundant and post a copy of the notice in a conspicuous place within the industrial establishment in which the employee is employed; or

- pay any employee whose employment is terminated as a result of the redundancy of the position two weeks’ wages at his or her regular rate

Once notice of termination has been given, an employer must:

- not reduce the rate of wages or alter any other term or condition of employment of the employee to whom the notice was given except with the written consent of the employee; and

- between the time when the notice is given and the date specified therein, pay to the employee his or her regular rate of wages for his or her regular hours of work.

Where employees to whom notice is given by their employer continue to be employed by the employer for more than two weeks after the date specified in the notice, they can have their employment terminated only with their written consent, or by again giving either a minimum of two weeks’ notice or termination pay of two weeks’ wages at the regular rate.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The requirements for notice or pay in lieu of notice do not apply in cases where the termination is by way of dismissal for just cause.

ONTARIO

Termination notice and/or pay and severance pay are minimum employment entitlements. They are independent from each other: each must be paid when required and they are calculated separately. They are not damages as they are not linked to any actual loss. A number of expressions are commonly used to describe situations when employment is terminated. These include “let go”, “discharged”, “dismissed”, “fired”, and “permanently laid off”. Under the Employment Standards Act, 2000 (ESA), a person’s employment is terminated if the employer:

- dismisses or stops employing an employee, including where an employee is no longer employed due to the bankruptcy or insolvency of the employer;

- “constructively” dismisses an employee and the employee resigns, in response, within a reasonable time; or

- lays an employee off for 35 or more weeks in a period of 52 consecutive weeks (longer than a “temporary layoff“).

An employee is entitled to written notice of termination (or termination pay instead of notice) if he or she has been continuously employed for at least 3 months. An employer can terminate the employment of an employee if they have given them written notice of termination and the notice period has expired. An employer can also terminate the employment of an employee without written notice or with less notice than is required if the employer pays termination pay to the employee (the notice and the number of weeks of termination pay together must equal the length of notice the employee is entitled to receive).

An employer does not have to provide an employee with a reason as to why the employment is being terminated. There are, however, some situations where an employer cannot terminate an employee’s employment even if the employer is prepared to give proper written notice or termination pay. For example, an employer cannot end someone’s employment, or penalize them in any other way, if any part of the reason for the termination of employment is based on the employee asking questions about the ESA or exercising a right under the ESA, such as refusing to work in excess of the daily or weekly hours of work maximums, or taking a leave of absence specified in the ESA. Please see the information on Anti-Retaliation/Reprisal Measures.

The amount of notice to which an employee is entitled depends on his or her “period of employment”; see Table 1 for details. A person is considered “employed” not only while he or she is actively working, but also during any time in which he or she is not working but the employment relationship still exists (e.g., time in which the employee is off sick or on leave or on lay-off), with the following exceptions:

- If a lay-off goes on longer than a temporary lay-off, the employee’s employment is deemed to have been terminated on the first day of the lay-off—any time after that does not count as part of the employee’s period of employment, even though the employee might still be employed for purposes of the “continuously employed for 3 months” qualification; or

- If two separate periods of employment are separated by more than 13 weeks, only the most recent period counts for purposes of notice of termination. It is possible, in some circumstances, for a person to have been “continuously employed” for three months or more and yet have a period of employment of less than three months. In such circumstances, the employee would be entitled to notice because an employee who has been continuously employed for at least three months is entitled to notice, and the minimum notice entitlement of one week applies to an employee with a period of employment of any length less than one year.

Table 1: Amount of Termination Notice Required in Ontario, for employees continuously employed for at least 3 months

| Period of Employment | Notice Required |

| Less than 1 year | 1 week |

| 1 year but less than 3 years | 2 weeks |

| 3 years but less than 4 years | 3 weeks |

| 4 years but less than 5 years | 4 weeks |

| 5 years but less than 6 years | 5 weeks |

| 6 years but less than 7 years | 6 weeks |

| 7 years but less than 8 years | 7 weeks |

| 8 years or more | 8 weeks |

During the statutory notice period, an employer must:

- not reduce the employee’s wage rate or alter any other term or condition of employment;

- continue to make whatever contributions would be required to maintain the employee’s benefits plans; and

- pay the employee the wages to which they’re entitled, which cannot be less than the employee’s regular wages for a regular work week each week.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Certain employees are not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay under the ESA. These include: employees who are guilty of willful misconduct, disobedience, or willful neglect of duty that is not trivial and has not been condoned by the employer. “Willful” includes when an employee intended the resulting consequence or acted recklessly, or knew or should have known the effects of their conduct would have; poor work conduct that is accidental or unintentional is generally not considered willful.

Employees who are hired for a specific length of time or until the completion of a specific task are not eligible for termination notice/pay unless:

- the employment ends before the term expires or the task is completed; or

- the term expires or the task is not completed more than 12 months after the employment started; or

- the employment continues for three months or more after the term expires or the task is completed.

Other employees who are not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay include:

- Employees who have been employed less than three months

- Construction employees (including road construction and sewer/watermain construction)

- Employees on temporary layoff

- Employees who do not return to work within a reasonable time after being recalled to work from a temporary layoff

- Employees who refuse an offer of reasonable alternative employment

- Employees who refuse to exercise their right to another position that is available under a seniority system

- Employees who have had their employment terminated when they reach the age of retirement in accordance with the employer’s established practice, but only if the termination does not contravene the Human Rights Code

- Employees who are terminated during or as a result of a strike or lockout at the workplace

- Employees who have lost their employment because the contract of employment is impossible to perform or has been frustrated by an unexpected or unforeseen event or circumstance, such as a fire or flood, that makes it impossible for the employer to keep the employee working. (This does not include bankruptcy or insolvency or when the contract is frustrated or impossible to perform as the result of an injury or illness suffered by an employee.)

Special Rules: For shipbuilding and repair workers, if a supplementary unemployment benefit plan applies to the employee and the employee or their union or agent agree in writing, the employee is not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay.

Mass Termination: Special rules for notice of termination may apply when the employment of 50 or more employees is terminated at an employer’s establishment within a 4-week period. This is often referred to as mass termination. (Note: an “establishment” can, in some circumstances, include more than one location.)

When a mass termination occurs, the employer must submit a ‘Form 1: Notice of Termination of Employment’ to the Director of Employment Standards. Any notice to the affected employees is not considered to have been given until a Form 1 is received by the Director of Employment Standards. In addition to providing employees with individual notices of termination, the employer must post a copy of the Form 1 provided to the Director of Employment Standards in the workplace where it will come to the attention of the affected employees on the first day of the notice period.

The amount of notice employees must receive in a mass termination is not based on each employees’ length of employment, but on the number of employees who have been terminated. An employer must give:

- 8 weeks’ notice if the employment of 50 to 199 employees is to be terminated

- 12 weeks’ notice if the employment of 200 to 499 employees is to be terminated

- 16 weeks’ notice if the employment of 500 or more employees is to be terminated

The mass-termination rules do not apply if the number of employees whose employment is being terminated represents not more than 10 per cent of the employees who have been employed for at least three months at the establishment and none of the terminations are caused by the permanent discontinuance of all or part of the employer’s business at the establishment.

UNITED KINGDOM

Employers are required to give at least one week’s notice for each year an employee has worked (e.g., three years of continuous work requires three weeks’ notice), to a maximum of 12 years/weeks. Employees must have worked at least one month to be eligible for termination notice.

Special Situations

Exemptions: If an employee has committed gross misconduct, the employer is not required to provide advanced notice of termination. Employees on a fixed term contract do not require notice unless the employer is ending the contract prior to its expiry date.

AUSTRALIA

In Australia, notice of termination and redundancy requirements are set out in the Fair Work Act 2009. The amount of notice required varies depending on the employee’s tenure; see Table 2 for details. Employers are required to either give written notice of termination for the minimum notice period, or pay the employee the equivalent rate of pay for the period that would have been worked.

Table 2: Minimum Termination Notice Period in Australia, as per the Fair Work Act 2009

| Employee’s Tenure | Minimum Notice |

| Not more than 1 year | 1 week |

| More than 1 year to 3 years | 2 weeks |

| More than 3 years to 5 years | 3 weeks |

| More than 5 years | 4 weeks |

Special Situations

Exemptions: The minimum notice period does not apply to:

- Employees employed for a specified period of time, for a specified task, or for the duration of a specified season

- Employees whose employment is terminated because of serious misconduct

- Casual employees

- Employees (other than apprentices) to whom a training arrangement applies and whose employment is for a specified period of time or to the duration of the training arrangement

- Daily hire employees working in the building and construction industry or in the meat industry in connection with the slaughter of livestock

- Weekly hire employees working in connection with the meat industry and whose termination of employment is determined solely by seasonal factors

Special Rules: If an employee is over 45 years old and has had job tenure of at least two years, they must receive one additional week’s notice of termination or the pay equivalent.

UNITED STATES

Some US states have specific laws related to termination of employment. Other states that do not have specific laws related to termination of employment operate under an ‘employment-at-will’ system. Under the ‘employment-at-will’ system, if there is no collective agreement or employment contract in place, an employer may terminate an employee at any time with no notice, and they are not required to provide a reason, so long as no other federal or state laws are violated in the process. An example of a potential violation of another applicable law are those that prohibit employment discrimination on the basis of age, race, color, religion, sex, ethnic/national origin, disability, and veteran status, which are enforced by the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Most employees in the US are employed on an ‘at-will’ basis.

Special Situations

Special Rules: Special rules apply to the employment rights of veterans in the United States. Veterans’ and reservists’ employment rights are protected under the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 and assistance is provided through the Department of Labor’s Veterans’ Employment and Training Service. These rights include:

- reemployment protection after an absence from work for military duty of up to 5 years (with some exceptions);

- employment protection and the right to accommodations for disabled veterans; and

- up to 2 years’ right to reemployment after injuries sustained during service or training

While in military service, service members are essentially thought to be on a leave of absence and have a right to return to work in a position with the same seniority, status, and pay as they would have attained had they not been serving. The Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act requires that advanced written or verbal notice is provided to employers when leave for military duty is taken, whenever possible.

Mass Termination: The Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act 1989 mandates that large organizations (essentially employers with 100 or more full-time employees) provide at least 60 days’ written advance notice in the case of plant closures and mass layoffs. For more on the specifics of federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act requirements, see the Department of Labor’s Employment and Training Administration’s Worker’s Guide to Advance Notice of Closings and Layoffs.

CALIFORNIA

The State of California allows employers to terminate employment relationships at will. However, employees cannot be terminated on the basis of discrimination related to race, ancestry, religion, age, disability, sex or gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, medical condition, genetic information, marital status, or military or veteran status. There is no legal requirement to provide notice of termination for any lawful termination.

ILLINOIS

Employers in the State of Illinois may terminate any employee at their will. However, termination of an employee on the basis of any of the following identities is prohibited by the Illinois Human Rights Act: race, color, religion, sex, national origin, ancestry, citizenship status, age, marital status, physical or mental handicap, or military status. No notice is required for any lawful termination.

NEW YORK

Employers in the State of New York may terminate any employee at their will. One notable distinction between New York and other ‘employment-at-will’ states is that in New York, at the time of hiring, employers are required to notify new employees in writing of some basic terms of their employment, such as the regular rate of pay, the pay day, any possible overtime rate, their method of payment, etc.

New York State’s labour law (section 201-d and section 215) sets out other exceptions to ‘employment-at-will’. Section 201-d prohibits an employer from firing an employee for any political or recreational activities undertaken outside of their work, for the legal use of consumable products outside of their work, or for their union membership. Section 215 prohibits employers from penalizing employees for filing complaints about any provision of the labour law.

Special Situations

Mass Termination:The federal Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act mandates that large organizations (essentially employers with 100 or more full-time employees) provide written advance notice in the case of plant closures and mass layoffs. New York State’s own Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act 2008 strengthens the provisions of the federal Act in a number of ways. For instance, instead of 60 days’ notice, 90 days’ notice is required. Warnings must be also provided to each of the following groups: all affected employees and any employee representatives, the New York State Department of Labor, and the Local Workforce Investment Board. For more on New York’s Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act 2008 visit the US Department of Labor’s website.

Termination Pay

CANADA

An employee who has completed at least three consecutive months of continuous employment with an employer who does not receive termination notice in writing at least two weeks before a date specified in the notice, is entitled to two weeks’ wages at their regular rate of wages for their regular hours of work, in lieu of the notice.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The requirements for notice or pay in lieu of notice do not apply in cases where the termination is by way of dismissal for just cause.

ONTARIO

An employee who has completed at least three consecutive months of continuous employment with an employer and who does not receive the written notice required under the ESA must be given termination pay in lieu of notice.

Termination pay is a lump sum payment equal to the regular wages for a regular work week that an employee would otherwise have been entitled to during the written notice period. Termination pay must also include vacation pay on the termination pay period. These payments must be paid within seven days of the employees’ next regular pay date, whichever is later. Employers must also continue to make whatever contributions would be required to maintain the benefits the employee would have been entitled to had they continued to be employed through the notice period. Termination pay is intended to assist the employee during a period in which new employment is sought.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Certain employees are not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay under the ESA. Employees who are hired for a specific length of time or until the completion of a specific task are not eligible for termination notice/pay unless:

- the employment ends before the term expires or the task is completed; or

- the term expires or the task is not completed more than 12 months after the employment started; or

- the employment continues for three months or more after the term expires or the task is completed.

Other employees who are not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay include:

- Employees who have been employed less than three months

- Construction employees (including road construction and sewer/watermain construction, and employees who are working off-site but who are commonly associated in work or collective bargaining with employees who work at the construction site)

- Employees on temporary layoff

- Employees who do not return to work within a reasonable time after being recalled to work from a temporary layoff

- Employees who refuse an offer of reasonable alternative employment

- Employees who refuse to exercise their right to another position that is available under a seniority system

- Employees who have had their employment terminated when they reach the age of retirement in accordance with the employer’s established practice, but only if the termination does not contravene the Ontario Human Rights Code

- Employees who are terminated during or as a result of a strike or lockout at the workplace

- Employees who have lost their employment because the contract of employment is impossible to perform or has been frustrated by an unexpected or unforeseen event or circumstance, such as a fire or flood, that makes it impossible for the employer to keep the employee working (this does not include bankruptcy or insolvency or when the contract is frustrated or impossible to perform as the result of an injury or illness suffered by an employee)

- Employees who are guilty of willful misconduct, disobedience, or willful neglect of duty that is not trivial and has not been condoned by the employer (“willful” includes when an employee intended the resulting consequence or acted recklessly, or knew or should have known the effects their conduct would have; poor work conduct that is accidental or unintentional is generally not considered willful)

Special Rules: For shipbuilding and repair workers, if a supplementary unemployment benefit plan applies to the employee and they or their union or agent agree in writing, the employee is not entitled to notice of termination or termination pay.

UNITED KINGDOM

Although there is no formal termination pay in the UK, aside from Redundancy Pay (see Severance Pay), employers can choose to provide ‘pay in lieu of notice’. In this case, an employee receives the amount in wages or salary that they would have received in the required notice period, i.e., according to length of employment. The employer must also pay any other contributions that are included in the employee’s employment contract (e.g., pension contributions or private health insurance) which the employee would also have received during their notice period.

AUSTRALIA

Employers are required to either give written notice of termination within the periods of notice outlined in Table 3 or pay the employee the equivalent rate of pay for the period that would have been worked. The rate of pay includes bonuses, loadings, monetary allowances, overtime rates, penalty rates, and any other separately identifiable amounts.

Table 3: Minimum Termination Payment in Lieu of Notice in Australia, as per the Fair Work Act 2009

| Employee’s Tenure | Payment Equivalent |

| Less than 1 year | 1 week |

| More than 1 year to 3 years | 2 weeks |

| More than 3 years to 5 years | 3 weeks |

| More than 5 years | 4 weeks |

Special Situations

Exemptions: The minimum notice period or pay in lieu for termination does not apply to:

- Employees employed for a specified period of time, for a specified task, or for the duration of a specified season

- Employees whose employment is terminated because of serious misconduct

- Casual employees

- Employees (other than apprentices) to whom a training arrangement applies and whose employment is for a specified period of time or to the duration of the training arrangement

- Daily hire employees working in the building and construction industry or in the meat industry in connection with the slaughter of livestock

- Weekly hire employees working in connection with the meat industry and whose termination of employment is determined solely by seasonal factors

Special Rules: If an employee is over 45 years old and has had job tenure of at least two years, they must receive one additional week’s notice of termination or the pay equivalent.

UNITED STATES

Employers are not required make termination payments to former employees unless otherwise outlined in a collective bargaining agreement or employment contract.

CALIFORNIA

An employer must pay employees for all services rendered up to the point of termination. In general, terminated employees must be paid all remaining wages, including accrued vacation pay, at the time of termination. Employers who violate this requirement may be fined a “waiting time penalty”, which can equal up to 30 days’ worth of pay for the terminated employee.

Special Situations

Special Rules: Employees who are terminated as a group from seasonal employment from work curing, canning, or drying perishable fish, fruit, and vegetables must be paid within 72 hours of being terminated. Terminated employees in the motion picture industry must receive their final pay at the next regular payday. Terminated employees who worked drilling oil must be paid within 24 hours of termination, excluding weekends and holidays.

ILLINOIS

An employee must only be paid for the time they have worked. When terminated, employees must be paid all outstanding wages, vacation pay, and bonuses at the next regularly scheduled payday.

NEW YORK

Termination pay is only required if outlined in an employment contract.

Severance Pay

CANADA

An employee who has completed at least 12 consecutive months of continuous employment with an employer is entitled to severance pay from an employer. Severance pay is calculated as the greater of either:

- 2 days’ wages at the employee’s regular rate of wages for his or her regular hours of work for each completed year of continuous employment with the employer; or

- 5 days’ wages at the employee’s regular rate of wages for their regular hours of work.

Special Situations

Exemptions: An employee is not entitled to severance pay if the severance occurs as a result of dismissal for just cause.

ONTARIO

Severance pay is compensation paid to qualified employees who have their employment “severed”. The purpose of severance pay is to compensate employees for years of service and for losses (such as loss of seniority) that occur when a long-term job is lost. Severance pay is not the same as termination pay, which is given in place of the required notice of termination of employment.

A person’s employment is considered “severed” when their employer:

- dismisses or stops employing an employee, including where an employee is no longer employed due to the bankruptcy or insolvency of the employer;

- “constructively” dismisses an employee and the employee resigns, in response, within a reasonable time;

- lays an employee off for 35 or more weeks in a period of 52 consecutive weeks (longer than a “temporary layoff“). [For the purposes of determining whether employment has been “severed”, an employee who receives less than one quarter of the wages they would have earned at the regular rate for a regular work week is considered to have been on a week of layoff. A week of layoff does not include a week when the employee is unavailable for work, unable to work, suspended for disciplinary reasons, or not provided with work because of a strike or lockout at their place of employment or elsewhere. Although the 52 weeks are consecutive, the 35 weeks do not have to be consecutive.];

- lays the employee off because all of the business at an establishment close permanently (an “establishment” can, in some circumstances, include more than one location); or

- gives the employee written notice of termination and the employee resigns after giving two weeks’ written notice, and the resignation takes effect during the statutory notice period. If an employer provides longer notice than is required, the statutory part of the notice period is the last part of the period that ends on the date of termination.

An employee is entitled to severance pay if their employment is severed and:

- the employee has been employed for five years or more (including all the time spent by the employee in employment with the employer, whether continuous or not and whether active or not); and

- the employer has either a payroll in Ontario of at least 2.5 million or severs employment of 50 or more employees within a 6-month period because all or part of its business closed.

The amount of severance pay an employee is entitled to receive is calculated by multiplying the employee’s regular wages for a regular work week by the sum of:

- the number of completed years of employment; and

- the number of completed months of employment divided by 12 for a year that is not completed.

The maximum amount of severance pay required to be paid is 26 weeks.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Certain employees are not entitled to severance pay, including:

- Employees who have been employed less than five years

- Construction employees (including road construction and sewer/watermain construction, and employees who are working off-site but who are commonly associated in work or collective bargaining with employees who work at the construction site)

- Maintenance employees (including the on-site maintenance of buildings, structures, roads, sewers, pipelines, mains, tunnels or other works)

- Employees who refuse an offer of reasonable alternative employment

- Employees who have their employment severed and retire on a full pension recognizing all years of service that would have been worked in the normal course (Canada Pension Plan benefits do not qualify)

- Employees whose employment is severed because of a permanent closure of all or part of the employer’s business that the employer can show was caused by the economic effects of a strike

- Employees who have lost their employment because the contract of employment is impossible to perform or has been frustrated by an unexpected or unforeseen event or circumstance, such as a fire or flood, that makes it impossible for the employer to keep the employee working (this does not include bankruptcy or insolvency or when the contract is frustrated or impossible to perform as the result of an injury or illness suffered by an employee)

- Employees who are guilty of willful misconduct, disobedience, or willful neglect of duty that is not trivial and has not been condoned by the employer (“willful” includes when an employee intended the resulting consequence or acted recklessly, or knew or should have known the effects of their conduct would have; poor work conduct that is accidental or unintentional is generally not considered willful).

UNITED KINGDOM

Although the UK does not require severance pay, it makes provisions for redundancy pay in situations where an employee is terminated because the employer no longer requires the job. Employees who have worked for an employer for two or more years are eligible for redundancy pay. Redundancy pay is calculated as:

- half a week’s pay for each full year worked when younger than 22 years of age

- one week’s pay for each full year worked when between 22 and 40 years of age

- one and a half week’s pay for each full year worked when 41 years of age or older

Payment is capped at 20 years’ service.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Employees are not entitled to redundancy pay if they were offered continued employment. In addition, the following types of employees are not entitled to redundancy pay:

- Former registered dock workers, share fishermen

- Crown servants, members of the armed forces, or police services

- Apprentices who are not employees at the end of their training

- Domestic servants who are a member of the employer’s immediate family

Special Rules: If an employee is made redundant on or after April 6th, 2019, their weekly redundancy pay is capped at £525 and the maximum statutory redundancy pay is capped at £15,750. If the employee was made redundant before 6 April 2019, these amounts are lower. Employees who were temporarily laid off for more than 4 weeks in a row or for more than six weeks within a 13 week period can also claim redundancy pay.

AUSTRALIA

Although Australia does not require severance pay, it makes provisions for redundancy pay in situations where an employee is terminated because the employer no longer requires the job, or is insolvent or bankrupt. Employees who are made redundant are entitled to their base rate of pay for ordinary hours worked for the number of weeks shown in Table 4. This payment does not include any additional compensation (such as bonuses or monetary allowances).

Table 4: Redundancy pay in Australia, by employee tenure

| Employee Tenure | Redundancy Pay Equivalent |

| 1 year to less than 2 years | 4 weeks |

| 2 years to less than 3 years | 6 weeks |

| 3 years to less than 4 years | 7 weeks |

| 4 years to less than 5 years | 8 weeks |

| 5 years to less than 6 years | 10 weeks |

| 6 years to less than 7 years | 11 weeks |

| 7 years to less than 8 years | 13 weeks |

| 8 years to less than 9 years | 14 weeks |

| 9 years to less than 10 years | 16 weeks |

| More than 10 years | 12 weeks |

Special Situations

Exemptions: Small business employers (who employ fewer than 15 employees) are not required to pay redundancy pay. In addition, redundancy pay will not be payable to any of the following:

- Employees whose period of continuous service with the employer is less than 12 months

- Employees employed for a specified period of time, for a specified task, or for the duration of a specified season

- Employees whose employment is terminated because of serious misconduct

- Casual employees

- Employees (other than apprentices) to whom a training arrangement applies and whose employment is for a specified period of time or is, for any reason, limited to the duration of the training arrangement

- Apprentices

- Employees to whom an industry-specific redundancy scheme in a modern award applies

- Employees to whom a redundancy scheme in an enterprise agreement applies if:

- the scheme is an industry-specific redundancy scheme that is incorporated by reference (and as in force from time to time) into the enterprise agreement from a modern award that is in operation; or

- the employee is covered by the industry-specific redundancy scheme in the modern award.

Special Rules: An employee’s current entitlement to redundancy pay can be dependent on whether they had an entitlement to redundancy pay prior to the introduction of the National Employment Standards on January 1, 2010. If an employee did not have an entitlement to redundancy pay prior to 1 January 2010, an employee’s period of continuous service with the employer will only accrue from 1 January 2010.

UNITED STATES

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not require severance pay upon termination of employment, unless it is part of an employment contract or collective agreement.

CALIFORNIA

There is no requirement for severance pay in the State of California.

ILLINOIS

There is no requirement for severance pay in the State of Illinois, unless it is otherwise stated in the employment contract.

NEW YORK

There is no requirement for severance pay in the State of New York, unless it is part of an employment contract. If an employee does receive severance pay, this may affect their eligibility for unemployment insurance benefits. Severance pay can also be referred to as dismissal pay in New York.

DEMONSTRATION

As we have learned throughout this module, precarious employment is frequently defined by a lack of certainty over continuing employment. Employment standards legislation can provide some protection against this uncertainty, by – for example – legislating necessary notice periods before termination and/or establishing provisions for severance pay that employers owe to dismissed employees. However, as the comparisons between jurisdictions covered in the ESD indicate, the extent of protection provided by minimum employment standards legislation can vary considerably. None of the American jurisdictions, for example, require severance pay and all operate according to an “at-will” employment model wherein employers may dismiss employees at any point without cause. Additionally, employees face differential degrees of job uncertainty across industries, occupations and forms of employment.

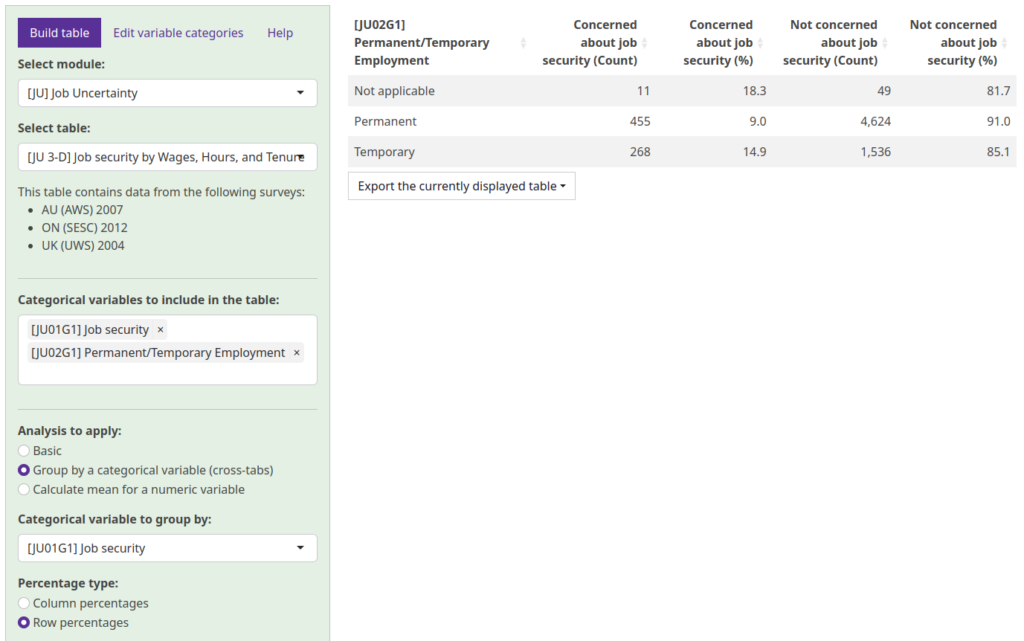

In this demonstration, we will explore issues of job uncertainty and termination using survey data from the jurisdictions covered by the ESD. Let’s begin by looking at respondents’ concern over continuing employment, using table JU 3-D, which includes data about job security by permanent and temporary forms of employment.

Note that this demonstration assumes that you are familiar with the basics of manipulating tables in the statistics database. If you are unsure how to choose which variables to display, remove variables or categories from tables, modify the table layout, calculate percentages, etc., please see our tutorial on using the statistics database.

Table 1a has been modified to group by Job Security, show row percentages, and to hide missing categories. We first compare respondents’ concern about job security by form of employment, i.e. whether they are in permanent or temporary forms of employment. According to Table 1a, which draws on data from the SESC, AWS and USW surveys, respondents in temporary employment were slightly more likely to be concerned about job security than those in permanent employment (14.9% versus 9.0%). However, it is notable that sizeable majorities of respondents in both permanent and temporary employment reported that they were not concerned about job security. This could alert us to the fact that precarious employment, particularly as it manifests as concerns about job uncertainty, can be highly concentrated among particular subsets of workers and in particular sectors of the labour market; these results could differ when looking at data from other surveys.

We can also add gender to our table to assess how gender is related to people’s concerns about job security in permanent and temporary employment. As Table 1b demonstrates, male respondents in temporary employment were slightly more likely to be concerned about job security than their similarly situated female counterparts: 16.8% of male respondents in temporary employment indicated they were concerned about job security, while 13.5% of female respondents in temporary employment did so. Female and male respondents in permanent employment expressed similarly low levels of concern about job security, at 8.7% and 9.3% respectively.

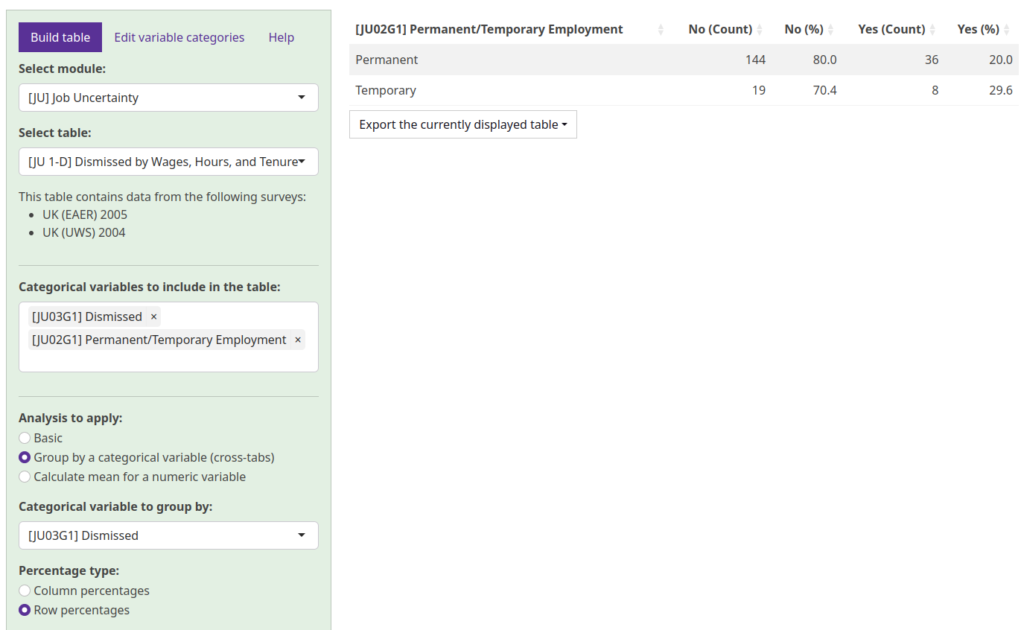

Last, let’s turn to the experience of job dismissal. As mentioned above, whether or not a respondent experienced a dismissal is treated as an indicator of overall job un/certainty. As in Tables 1a and b above, we can explore incidences of job dismissal across permanent and temporary forms of employment by looking at table JU 1-D, which includes variables related to dismissal and form of employment.

Here again we can see evidence of the negative impact of temporary forms of employment on overall job security. Table 2 shows that dismissals were more common among those respondents in temporary employment. (Note that respondents who did not answer the question have been filtered out of this table for readability). Almost a third (29.6%) of respondents who were in temporary employment had previously experienced a job dismissal, while only 20.0% of respondents who were in permanent employment had previously experienced dismissal.

The rise of temporary, casual and other forms of short-term employment have eroded job security in particular pockets of the contemporary labour market. The uncertainty over continuing employment, and consequently the uncertainty over stable income, are key dimensions of precarious employment. The tables shown in this demonstration give researchers some indication of the prevalence of these issues in the jurisdictions and populations included in the ESD. Those who wish to learn more about job security, job duration and dismissal are encouraged to search these terms in the thesaurus and consult the many secondary sources found in the ESD library. To read more about how to use each of the databases, please see the following tutorials:

Works Cited

Campbell, I. (2008). “Australia: Institutional Changes and Workforce Fragmentation.” In S. Lee & F. Eyraud (Eds.), Globalization, Flexibilization and Working Conditions in Asia and the Pacific (pp. 115-152). Geneva, Switzerland & Oxford, UK: International Labour Office, in association with Chandos.

Campbell, I., & Burgess, J. (2001). “Casual Employment in Australia and Temporary Work in Europe: Developing a Cross-national Comparison.” Work, Employment & Society, 15(1), 171-184.

Commission for Labor Cooperation (2003). The Rights of Nonstandard Workers: A North American Guide. Washington, DC: Secretariat of the Commission for Labor Cooperation.

Fuller, S., & Vosko, L. F. (2008). “Temporary Employment and Social Inequality in Canada: Exploring Intersections of Gender, Race and Immigration Status.” Social Indicators Research, 88(1), 31-50.

Hyde, A. (1998). “Employment Law after the Death of Employment.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law, 1, 99-115.

O’Donnell, A. (2004). “‘Non-standard’ Workers in Australia: Counts and Controversies.” Australian Journal of Labour Law, 17, 1-28.

Sinclair, P. R., MacDonald, M., & Neis, B. (2006). “The Changing World of Andy Gibson: Restructuring Forestry on Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula.” Studies in Political Economy, 78, 177-199.

Stewart, A. (1992). “‘Atypical’ Employment and the Failure of Labour.” Australian Bulletin of Labour, 18(3), 217-235.

Summers, C. W. (2000). “Employment at Will in the United States: The Divine Right of Employers.” University of Pennsylvania Journal of Labor and Employment Law, 3(1), 65-86.

Vosko, L. F. (2000). Temporary Work: The Gendered Rise of a Precarious Employment Relationship. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2006). “Precarious Employment: Towards an Improved Understanding of Labour Market Insecurity.” In L. F. Vosko (Ed.). Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada (pp. 3-39). Montreal, QC & Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2010b). “A New Approach to Regulating Temporary Agency Work in Ontario or Back to the Future?” Relations Industrielles/Industrial Relations, 65(4), 632-653.

Watson, I. (2005). “Contented Workers in Inferior Jobs? Re-assessing Casual Employment in Australia.” Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(4), 371-392.