Working Time

WORKING TIME

Contents

This module allows researchers to explore the features of employment standards (ES) related to working time, rest periods, and overtime across different jurisdictions. It is organized around two key research questions:

- What are the central features of legislative limits on working time, rest periods, and overtime and how do these features differ across the national and sub-national jurisdictions?

- How are the features of legislative limits on working time, rest periods, and overtime related to employees’ social location (e.g., social relations of gender, race/ethnicity, migration status, age, ability), social context (i.e., occupation and industry), and job characteristics?

This module is comprised of an introduction to the ESD’s organizing themes and concepts surrounding working time and a description of the indicators devised on the basis of legislative details governing working time in the jurisdictions covered by the ESD. It also includes statistical tables incorporating survey data, a searchable library of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources, and a thesaurus of terms. These elements seek to provide a package of conceptual tools and guidelines for research.

KEY CONCEPTS

Limits on Working Time

Weekly and Daily Maximums: Limits on working time are critical to fostering health and safety among employees, maintaining distinctions between ‘work time’ and ‘non-work time’, and ensuring that employees can engage in activities beyond work, including domestic and caring work as well as leisure activities.

Establishing limits on hours of work emerged as a key struggle of labour movements from the mid-1800s. Limits on working hours established in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century applied primarily to children (Lee, McCann, & Messenger, 2007). In Britain, the British Factory Act of 1833 established a 12-hour working day for youth between 13 and 18 years of age (Vosko, 2010, p. 28). In Ontario, maximum hour regulations date to the Factories Act of 1884 which set a 60-hour weekly maximum for women and children (Thomas, 2004; Tucker, 1990).

Subsequent legislation adopted in numerous jurisdictions established maximum hour limits for most adults. Many European countries adopted legislation establishing a 10-hour daily limit by the beginning of World War One (Lee, McCann, & Messenger, 2007). The first International Labour Organization (ILO) convention adopted in 1919 set an 8-hour daily maximum and a 48-hour weekly maximum. Subsequently, in Ontario, the 1944 Hours of Work and Vacations with Pay Act was the first working time legislation in the province to apply to adult workers, both male and female. It established maximum hours of work of 8 per day and 48 per week for employees in all ‘industrial undertakings.’

Employment standards set limits on working hours in several ways. First, they can establish the maximum number of work hours an employee can work in a day and a week. Such maximums vary by jurisdiction. For example, in Ontario, the daily maximum is 8 hours, or the number of hours in an established regular workday. The 8-hour limit can be exceeded if there is a written agreement between the employee and employer. The weekly limit on hours of work in Ontario is 48 hours for most employees. Exceeding this limit is also possible if there is a written agreement between the employee and the employer. While not an in depth focus in the ESD, France is notable for its relatively low weekly limit of 35 hours for workplaces with more than 20 employees, introduced in 2000. By contrast, in the US, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not set out maximum daily or weekly work hours.

Minimum Time Free from Work: Limits on maximum working hours are not the only way that employment standards can limit working time. Employment standards can also establish a legal minimum amount of time free from work, often in the form of a minimum number of hours free from work each day, and/or a minimum number of hours free from work each week. Such standards have been an important factor in fostering the 40-hour per week convention of the standard employment relationship.

In Ontario, legislation establishing a mandatory period free from work was the first form of working time regulation. The Lord’s Day Act of 1845 prohibited a range of activities on Sundays, including employment. Several ILO conventions address the right of workers to 24 hours free from work per week, including the Weekly Rest (Industry) Convention, 1921 and Weekly Rest (Commerce and Offices) Convention, 1957.

Outside employment standards, the need for working time limits is recognized in human rights policies. For example, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights establishes a right to ‘reasonable limitation’ on working time and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights calls for working hour limits as a condition of just working conditions (Lee, McCann, &, Messenger, 2007). In addition, the European Working Time Directive requires EU countries to enforce a weekly limit on working hours not exceeding 48 hours including overtime, a minimum daily rest period of 11 hours, and a minimum weekly rest period of at least 24 consecutive hours, among other provisions.

Overtime

Overtime regulations are another way in which employment standards shape working time in a given jurisdiction. Overtime hours are hours worked beyond a fixed daily or weekly threshold that varies by jurisdiction. For example, in the US, under the FLSA, the overtime threshold is 40 hours per week. In Ontario, the overtime threshold is 44 hours per week. Employees who work overtime hours may be entitled to an overtime premium above their basic rate of pay. For example, in both Ontario and the US, employees entitled to the overtime premium can earn 1.5 times their basic rate of pay for overtime hours. The requirement to pay employees a premium for working overtime is intended to limit employers’ reliance on long working hours, and it works in conjunction with other working time regulations to shape the 40-hour week convention.

Overtime regulations are circumscribed in numerous ways. Some jurisdictions allow for averaging agreements. These are agreements between an employee and an employer that allow for hours of work to be averaged over two or more weeks for the purposes of calculating entitlement to overtime pay. Averaging means that overtime pay will be payable only if the average number of hours per week in the averaging period exceeds the overtime threshold. Many jurisdictions have established numerous exemptions that limit certain employees’ access to overtime pay. In the US, under the FLSA, Executive, Administrative, Professional, Computer, and Outside Sales Employees are exempt from overtime pay. In Ontario, overtime pay exemptions exist for Homecare Workers, Farm Employees, and Managers/Supervisors, among many others.

Rest Periods

Employment standards can also set minimum rest periods. In the UK, for example, employees have the right to a rest break during working hours of no less than 20 minutes if they work over six hours in a day. In Ontario, employees are entitled to a 30-minute eating period after no more than five hours of work. Employees and employers can agree to split this eating period into two breaks of 15 minutes.

Working Time Conventions in Transition

A combination of legislation and collective bargaining helped to establish the 40 hour per week and 8 hour per day norm of full-time employment, which reached its apex in industrialized countries following World War Two (Fudge, 1991). This norm of working time was premised on a gender contract of male breadwinning and female dependent caregiving. Yet this norm has undergone erosion for several decades. The growing participation of women in the paid labour force, the growth of part-time work, more diverse patterns of lifelong learning, and the growing range of leaves available to employees are fostering work arrangements that diverge from the postwar standard of working time.

Changes to working time norms are also fueled by increasingly flexible forms of work organization. The rise of just-in-time and lean production, and more recently, automated scheduling technology, have led to new ways of scheduling workers more closely driven by the varying volume of businesses’ activities (Lee, McCann, &, Messenger, 2007; Thomas, 2007). In many sectors there has been growing unpredictability in the working time of employees, especially in relation to on-call work, schedules with short notice, zero-hours contracts, among other developments. Increasingly flexible scheduling practices impose difficulties on employees’ ability to manage extra-work activities, engage in care work, or hold a second job. Such practices exacerbate workplace power imbalances and further diminish employees’ control over the labour process.

In response to deepening insecurity in the area of working time, workers’ advocates are calling for the passage of legislation that establishes in law principles of fair scheduling. Such principles might include a legal requirement for employers to provide employees two weeks’ notice of their schedule, and to provide new employees a good-faith estimate of the minimum hours of work per month and the days and hours of those shifts. In response to workers’ advocates’ demands, numerous jurisdictions are adopting policies that provide employees with greater degrees of predictability and fairness in working time arrangements.

INDICATORS

Working time indicators can be grouped into three important areas: “Regular Working Time,” “Overtime,” and “Periods Free from Paid Work.” The purpose of these measures is to identify the degree to which survey respondents are entitled to maximum working time coverage as well as overtime regulations given their occupation and workplace information. Overall, these indicators can be examined to better understand the employment standards related to overtime compensation policies and regulation across different jurisdictions in Canada, the US, the UK, and Australia.

First, six variables capture information on regular working time. Two variables capture the usual and actual hours worked per week (WT01G1, WT02G1). These variables measure if a person’s usual and actual weekly working hours are above the jurisdictional maximum working hours in their main or all jobs. Second, two variables focus on the measures of whether a respondent works overtime and their overtime compensation (WT03G1, WT04G1).

Detailed information on regulations in different jurisdictions in this module provides guidance for understanding the national contexts of employment standards related to limits on working time, overtime, and periods free from paid work.

JURISDICTION MAPPING INFORMATION

Legal Maximum Number of Work Hours per Week

CANADA

Work hours, rest, and overtime are all regulated under Part III of the Canada Labour Code (CLC), which applies to workers in federally regulated industries. The CLC specifies that its regulations should be considered minimal conditions and should not affect any rights or benefits granted by law, custom, contract, or arrangement (including collective agreements) that are more favorable to an employee.

The CLC specifies standard work hours on a daily and weekly basis. The standard work hours are 8 hours a day and 40 hours a week. The maximum hours an employee may work each week is 48 hours.

The CLC allows employers flexibility over the scheduling of both standard work hours and maximum work hours by permitting, averaging, and modified work schedules. When the nature of work in an industrial establishment necessitates irregular working hours due to seasonal or other factors, the employer is allowed to average the total daily and weekly hours worked over two or more weeks. This can be done for a specified period agreed to in writing by the employer and the employees’ union or, in the absence of a union or collective agreement, in a vote in which at least 70 percent of affected employees agree to it.

Modified work schedules refer to schemes such as compressed work weeks and flexible hours of work. For example, employees may be scheduled to work 10 hours a day for four days a week, instead of eight hours a day for five days a week. The requirements to establish a modified work schedule are similar to those required under averaging arrangements.

Special Situations, number of overtime hours worked per week (paid and unpaid), andSpecial Situations

Exemptions: Hours of work provisions do not apply to employees who are managers or superintendents or exercise management functions. Architects, dentists, engineers, lawyers, and medical doctors are also exempt.

Special Rules: Special rules regarding hours of work apply to employees in Trucking, East Coast and Great Lakes shipping, West Coast shipping, Railways, and Commission salespersons in Broadcasting.

Ministerial Permits: An employer may apply to the Minister of Labour for a permit to allow employees to work in excess of the maximum permitted hours if there are exceptional circumstances to justify this. The Minister may issue such a permit if: s/he is convinced of the legitimacy of the employer’s need; the employer had posted a notice of the application for a permit for at least 30 days before its proposed effective date, in places readily accessible to the affected class of employees where they were likely to see it; or those employees are represented by a trade union and the employer had informed the trade union in writing of the application for the permit. The permit should specify the period for such modification, which should be no longer than the period within which the exceptional circumstances that justified the permit are expected to continue. It should also specify that either: (a) the total of the number of additional hours in excess of the maximum weekly hours; or (b) the additional hours that may be worked in any day and in any week during the period of the permit.

Emergency Work: The maximum hours of work in a week may be exceeded in cases of:

- accident to machinery, equipment, plant or persons;

- urgent and essential work to be done to machinery, equipment or plant; or

- other unforeseen or unpreventable circumstances.

ONTARIO

The Ontario Employment Standards Act (ESA) specifies maximum working hours on both a daily and a weekly basis.

The maximum number of hours most employees can be required or allowed to work in a day is 8 hours, or the number of hours an employer has established as the employee’s regular work day, if it is longer than eight hours.

The maximum number of hours most employees can be required to work in a week is 48 hours. The weekly maximum can be exceeded, up to a maximum of 60 hours per week, if: i. there is a written agreement between the employer and the employee, signed after the employee has been provided with the document entitled “Information for Employees About Hours of Work and Overtime Pay,” published by the Director of Employment Standards; or ii. the employer receives approval from the Director of Employment Standards. However, if the approval is still pending after 30 days of putting in the request, the employer may require employees to start working more than 48 hours a week as long as certain conditions are met, and the employee does not work more than 60 hours in a work week, or the number of hours the employee agreed to in writing, whichever is less.

An agreement between an employee and an employer to work additional daily or weekly hours, or an approval from the Director of Employment Standards for excess weekly hours, does not relieve an employer from the requirement to pay overtime pay where overtime hours are worked. Overtime must be paid for every hour worked over 44 hours in week (see the section on Overtime Pay for more information).

The ESA does not contain any restrictions on the timing of an employee’s shift other than the requirements for daily rest and rest between shifts described below. It also does not require an employer to provide transportation to or from work if an employee works late.

Commuting time is usually not seen as working time. Commuting time for an employee who has a regular work location is the time it takes him or her to get to work from home and vice versa. There are some situations where commuting time has been seen as working time (e.g., an employee takes a work vehicle home in the evening for the convenience of the employer or where the employee is required to transport supplies or other staff to or from the workplace or work site). The time an employee spends getting to or from a place where work was or will be performed, if it is not the employee’s regular workplace, is also considered working time.

Time spent by an existing employee in training that is required by the employer or by law is considered to be working time. Time spent in training that is optional to the employee (i.e., not required by the employer in order for the employee to continue in his or her job) would not be considered working time.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Several categories of employees and professionals are exempt from the ESA’s provisions around maximum working time. Those employees not covered by the ESA’s maximum working time regulations include:

- Chiropractors

- Dentists

- Firefighters

- Massage therapists

- Naturopaths

- Optometrists

- Pharmacists

- Physicians and Surgeons

- Physiotherapists

- Residential care workers

- Respiratory therapists

- Veterinarians

- Architects

- Information technology specialists

- Lawyers

- Managers and Supervisors

- Ontario Government employees

- Engineers

- Public accountants

- Surveyors

- Teachers

- Road construction and maintenance

- Sewer and watermain construction

- Swimming pool installation and maintenance

- Farm employees

- Fishers

- Flower growers

- Workers growing sod, trees, or shrubs

- Fruit, vegetable, and tobacco harvestors

- Horse boarders and breeders

- Hunting and fishing guides

- Workers keeping furbearing mammals

- Homecare employees

- Landscape gardeners

- Residential building superintendents, janitors, and caretakers

- Embalmers and Funeral directors

- Workers in the film and television industry

- Travelling salespersons

- Real estate salespersons and Brokers

The Ontario Ministry of Labour also provides further information pertaining to the ESA’s various exemptions and special rules in the form of a special guide through their website.

Exceptional Circumstances: There are exceptional circumstances where an employer may require employees to work more than the daily or weekly work limits, or to work during a period that otherwise requires time off for the employee. The ESA’s exceptional circumstances apply only when it is necessary to avoid serious interference with the ordinary working of the employer’s operations.

The ESA defines Exceptional Circumstances as existing when:

- there is an emergency;

- something unforeseen occurs that would interrupt the continued delivery of essential public services, regardless of who delivers these services;

- something unforeseen occurs that would interrupt continuous processes;

- something unforeseen occurs that would interrupt seasonal operations; and/or

- it is necessary to carry out urgent repair work to the employer’s plant or equipment.

Such exceptional circumstances could arise from such things as:

- a natural disaster/very extreme weather;

- a major equipment failure;

- fire or flood (even if not caused by a natural disaster or extreme weather); and/or

- an accident or breakdown in machinery that prevents others in the workplace from doing their jobs (e.g., the shutdown of an assembly line in a manufacturing plant).

Seasonal weather or market related pressures, or those that arise from the production or business cycle, are not considered exceptional circumstances. Examples of these include:

- rush orders being filled;

- periods of inventory-taking;

- when an employee does not show up for work;

- poor weather slows shipping or receiving;

- seasonal busy periods (e.g., Christmas); and/or

- routine or scheduled maintenance.

UNITED KINGDOM

In the United Kingdom, the legislation that applies to the legal maximum number of work hours per week is the amended Working Time Regulations (effective August 1, 2003). The Health and Safety Executive is responsible for the enforcement of weekly maximum working time limits in the UK.

Under Working Time Regulations (2003), the general rule is that an employee cannot work more than 48 hours per week on average, where an average workweek is calculated by averaging it over a 17-week period. When calculating the average number of hours worked per week, working hours will include the following: job-related training, business lunches, time spent travelling if the worker travels as part of their job, time spent working abroad, paid overtime, unpaid overtime that a worker is asked to perform, on-call time spent in the workplace, travel time between home and work if there is no fixed workplace, and any other time considered working time under the employment contract. Working hours will not include: breaks when no work is performed, on-call time spent away from the workplace, travelling outside of working hours, unpaid overtime that a worker has volunteered for, any paid or unpaid holiday, or travel to and from work if there is a fixed workplace.

Workers may voluntarily choose to opt-out of the 48 hour per week average limit, meaning they are willing to work above 48 hours per week on average, provided that they do so in writing with their employer. An employer may ask an employee to sign an opt-out agreement; however, employees cannot be punished or fired for refusing to sign an opt-out agreement. Opt-out agreements last for a specified or an indefinite period of time and they may be cancelled by an employee at any time, even when it is written into an employment contract. An employer must be given a minimum of 7 business days’ notice to cancel an opt-out agreement, although additional notice (up to 3 months) may be required if this is indicated as a condition in the opt-out agreement. An employer cannot require the cancellation of an opt-out agreement.

Workers holding more than one job should not be working a combined total of more than 48 hours per week on average.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Some exemptions apply to the 48 hour per week on average limit. When 24-hour shiftwork is required, or when working time is not measured and the employee is in control of determining his or her own working hours, the 48 hour per week limit does not apply. Likewise, the 48 hour per week on average limit does not apply if the employee works:

- as a domestic servant in a private household;

- in the armed forces;

- in security or surveillance;

- in emergency services or for the police; or

- as a seafarer, sea-fisherman, or worker on vessels on inland waterways

Special Rules: Employees under 18 years of age cannot work more than 40 hours in any given week and cannot work more than eight hours per day. They also cannot opt-out of the 40-hour per week limit.

As of August 1, 2004, Working Time Regulations were extended to apply working time measures to junior doctors.) However, junior doctors use a 26-week reference period, instead of the usual 17-week period, to calculate their weekly average hours of work. Employees in the offshore oil and gas sector use a 52-week reference period to calculate their average hours of work.

Employees who are not eligible for opting out of the 48 hour per week average limit (i.e., they cannot hold opt-out agreements) include:

- Airline staff

- Workers on boats or ships

- Workers in the road transportation industry

- Security guards on vehicles carrying high-value goods

- Other workers who travel in and operate vehicles covered by EU regulations concerning drivers’ hours

AUSTRALIA

Australia’s National Employment Standards determine the maximum weekly hours of work for all employees covered by the national workplace relations system. For full-time employees, an employer may not request an employee work more than 38 hours in a week unless the additional hours are reasonable. For any employees other than full-time employees, an employer may not request an employee to work the lesser of either 38 hours in a week or the employee’s regular hours of work in a week, unless the additional hours are reasonable. An employee may refuse to work any additional hours if the request is unreasonable.

If additional hours are deemed reasonable, there is no legal maximum number of weekly hours of work outlined in the National Employment Standards (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 62-64). Maximum hours of work (including additional hours thought to be reasonable) may be outlined in any applicable modern award or enterprise agreement.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The Fair Work Act (2009) outlines Australia’s National Employment Standards and these standards along with the national minimum wage apply to all national workplace relations system employees. Workers not covered by the national workplace relations system are instead covered by applicable state-level industrial relations systems, including:

- Employees in the state public sector in Tasmania

- Employees in the state public sector or local government in New South Wales, Queensland, or South Australia

- Employees in the state public sector or a non-constitutional corporation in either the local government or private industry in Western Australia

In these cases, only the state system would apply. For instance, the Government of Western Australia has its own state system which applies to employees of businesses that are sole traders, unincorporated partnerships, unincorporated trust agreements, and some incorporated associations.

Special Rules: Arrangements for averaging hours of work over a period greater than a week may apply if provisions are indicated in a modern award or enterprise agreement (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 63). The average weekly hours over the period may not exceed more than 38 hours for full-time employees or, for any employees other than full-time employees, the lesser of either 38 hours or an employee’s regular weekly hours of work. Employees who do not have an award or agreement may come to a written agreement with their employers to average their regular hours of work; however, this is not required; it is unlawful for an employer to try and force an employee to make an averaging agreement. The maximum averaging period possible is 26 weeks.

UNITED STATES

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) does not include any rules limiting the number of hours per week (or days per week) that an employee can be required to work.

CALIFORNIA

The State of California does not limit the number of hours that an employee can be required to work in any given week. However, an existing law states that “no employee shall be terminated or otherwise disciplined for refusing to work more than 72 hours in any workweek, except in an emergency.”

ILLINOIS

There is no legislated maximum number of hours that an employee can work in the State of Illinois.

NEW YORK

There is no specific legislation regulating the maximum number of hours an adult individual can work per week.

Overtime

CANADA

An employee who works for more hours than the standard hours of work, either 8 hours a day, or 40 hours a week, qualifies for overtime pay. If the total of daily overtime hours differs from the total of weekly overtime hours, the greater of the two amounts is used in calculating overtime payments.

Overtime pay is at least 1.5 times the regular hourly rate of wages. In an averaging situation, overtime applies after the standard hours in the averaging period are exceeded. Standard hours are determined by multiplying the number of weeks in the averaging period by 40. When a general holiday occurs during the week, the weekly standard hours (normally 40) must be reduced by 8 hours for every general holiday. For example, if an employee works more than 32 hours in a week with one holiday, they must be paid overtime for the excess hours worked.

ONTARIO

Overtime is not calculated on a daily basis. For most employees, whether they work full-time or part-time or are students, temporary help agency assignment employees, or casual workers, overtime begins after they have worked 44 hours in a work week or over a longer period under an averaging agreement. Hours worked after 44 in a standard work week or over a longer period under an averaging agreement must be paid at the overtime pay rate. Overtime pay is 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate of pay (often called “time and a half”).

Some employees have jobs where they are required to do more than one kind of work. Some of the work might be specifically exempt from overtime pay, while other parts might be covered. If at least 50 percent of the hours the employee works are in a job category that is covered, the employee qualifies for overtime pay.

An employee and an employer can agree in writing that the employee will receive paid time off work instead of overtime pay. This is sometimes called “banked” time or “time off in lieu.” If an employee has agreed to bank overtime hours, he or she must be given 1.5 hours of paid time off work for each hour of overtime worked. Paid time off must be taken within three months of the week in which the overtime was earned or, if the employee agrees in writing, it can be taken within 12 months.

If an employee’s job ends before he or she has taken the paid time off, the employee must receive overtime pay. This must be paid no later than seven days after the date the employment ended or on what would have been the employee’s next pay day.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Many employees have jobs that are exempt from the overtime provisions of the ESA, including:

- Ambulance drivers

- Firefighters

- Residential care workers

- Taxicab drivers

- Farm employees

- Harvesting workers

- Residential building superintendents

- Janitors

- Caretakers

- Others work in jobs where the overtime threshold is more than 44 hours in a work week (see the Special Rules section)

Managers and supervisors do not qualify for overtime if the work they do is managerial or supervisory. Even if they perform other kinds of tasks that are not managerial or supervisory, they are not entitled to get overtime pay if these tasks are performed only on an irregular or exceptional basis.

Special Rules: Some employee groups are covered by overtime regulations, but the weekly threshold of hours worked before overtime is due varies from the general overtime rule. For example, if Road Maintenance Workers are engaged at the site of road maintenance in relation to streets, highways, or parking lots, they are entitled to overtime pay for hours worked in excess of 55 in a work week. If they are engaged at the site of road maintenance in relation to structures, such as bridges or tunnels, they are entitled to overtime pay for hours worked in excess of 50 in a week. In either case, limited averaging of hours over two successive work weeks is permitted without the approval of the Director of Employment Standards.

Likewise, sewer and watermain construction workers are entitled to overtime pay only for hours worked in excess of 50 in a work week.

If a hospitality industry employee is provided with room and board and works no more than 24 weeks in a calendar year for the employer, the general overtime rule does not apply. The employee is instead entitled to overtime pay for hours worked in excess of 50 in a work week. This special rule concerning overtime pay applies only if the employee is employed by the owner or operator of the hotel, motel, tourist resort, restaurant, or tavern.

Highway transport truck drivers are entitled to overtime pay for hours worked in excess of 60 in a work week; however, only hours in which the driver is directly responsible for the truck are counted.

Homemakers (including personal support workers) are not entitled to overtime pay if the homemaker is paid the minimum wage for hours worked in a day to a maximum of 12 hours.

UNITED KINGDOM

In the United Kingdom, there is no legal obligation for an employer to pay extra for any overtime hours worked. Any applicable overtime pay rates and how these are calculated may be noted in an employment contract. Overtime hours refer to any hours worked beyond the normal hours of work indicated in the employment contract. Employees are only obligated to work overtime if it is written into their employment contract. Even when overtime is required, an employee cannot be forced to work beyond 48 hours per week. They may choose to work beyond 48 hours per week voluntarily, if they agree to do so in writing. An employer may stop an employee from working overtime unless it is written into their employment contract. Some employers may offer employees paid time off in lieu of paying overtime rates.

AUSTRALIA

For all employees covered by the national workplace relations system, which sets out who is covered by National Employment Standards and other relevant pieces of legislation, overtime applies whenever an employee works beyond their ordinary hours, works outside of the agreed number of hours, or works outside of the spread of ordinary hours (the time of day when ordinary hours are worked, i.e., 8am to 8pm). For employees not covered by an award or agreement, ‘ordinary hours’ of work refers to the number of hours agreed upon in their employment contract or in their employment roster. Employers may make reasonable requests for employees to work overtime. Employees may refuse the request if it is unreasonable. However, because overtime rates are not stipulated in the National Employment Standards, overtime is effectively an award or agreement based entitlement. Overtime rates only apply to award or agreement-free employees as a discretionary benefit.

Modern awards and enterprise agreements will specify overtimes rates and when these apply (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 139). Overtime typically receives a higher rate of pay than ordinary hours of work. Some awards or agreements may specify that time may be taken off work in lieu of payment (also know as: time off in lieu, or TOIL). The Fair Work Ombudsman’s website contains a Pay and Conditions Tool (or PACT), which allows employees and employers to calculate things like rates of pay (including allowance and penalty rates), shift rates, overtime rates, and entitlements (including annual leave, sick and carer’s leave, and employment ending entitlements).

UNITED STATES

Under the FLSA, employees are entitled to overtime pay for any hours worked after the first 40 in any given week. The rate of premium pay for overtime must not be less than 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate of pay.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The FLSA’s overtime rules do not apply to workers who are exempt from the FLSA. These include executive, administrative, and professional workers, as well as those working in the computer industry and in outside sales. Further details on these exemptions and their application can be found here.

CALIFORNIA

In California, employees are considered to have worked overtime if they work:

- more than eight hours in one day;

- more than 40 hours in one week; or

- more than six days in one week

Daily overtime premium pay must be no less than 1.5 times the employee’s regular wage for the 8th through 12th hours of work. If an employee works a shift that is longer than 12 hours, they are entitled to double their regular wage for the extra hours.

Weekly overtime (over 40 hours or over six days of work) receives premium pay of 1.5 times the regular wage for the first eight hours of overtime, and two times the regular wage for anything beyond that.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The groups who are regularly exempt from labour codes are likewise exempt from overtime protections: executive, administrative, and professional employees; employees who are employed in the computer software field and are paid on an hourly basis; state employees; and outside salespeople.

There are some other groups of employees who are exempt from overtime rules, including:

- Ambulance drivers with appropriate agreements

- Workers who are the parent, spouse, or child of the employer

- Individuals participating in a “national service program”

- Most drivers, including taxi drivers

- Workers covered by a collective agreement that effectively establishes a premium rate for overtime work

- Employees whose earnings exceed 1.5 times the minimum wage and who are also paid on commission

- Student nurses

- Airline employees who work more that 40 but fewer than 60 hours during a week, as a temporary modification in their regular schedule

- Carnival ride operators

- Crew members working on commercial fishing boats

- Professional actors

- Motion picture projectionists

- Announcers, news editors, and chief engineers for radio and television stations in small cities and towns

- Any employee who is engaged in work that is “primarily intellectual, managerial, or creative” and who works full-time, earning more than double the State monthly minimum wage

- Sheepherders

- Irrigators

- Babysitters

Special Rules: If an employee and their employer have a validly adopted agreement in which the employee may work more than 8 hours in any given day, the premium pay must only kick in after the established hours of work per day. In these cases, the increased premium pay must still begin after 12 hours have been worked in one day. This applies to all employees in this situation. For employees in the healthcare industry with valid agreements increasing the hours they may work in one day, these rules apply; however, it should be noted that the weekly premium pay (for any hours over 40) must be only 1.5 times the regular wage and there is no point at which weekly overtime premium pay increases to two times the regular wage.

Employees in hospitals or other similar facilities who care for the ill, disabled, or aged who work “in accordance with a 14 consecutive day work period in lieu of a workweek of seven consecutive days” are entitled to premium pay for work performed over 80 hours in a 14-day period. This must be paid at a rate of 1.5 times the regular wage. No double time is required.

Camp counselors may work up to 54 hours per week, and a maximum of 6 days per week without receiving overtime. Beyond that, they are entitled to 1.5 times the regular wage. No double time is required.

Personal attendants are not covered by the daily overtime rules. If they work over 40 hours per week, premium pay at a rate of 1.5 times the regular wage is required. There is no double time required. The exact same rules apply to residence managers of homes for the aged which have 8 or fewer beds.

Employees who are directly responsible for the 24-hour residential care of minors are entitled to premium pay of 1.5 times the regular rate for any hours worked over the weekly maximum of 40. If the employee works more than 48 hours in one week, they must be paid double time for the extra hours. If an employee works more than 16 hours in one day, the extra hours must be paid at two times the regular rate.

Employees of ski establishments have an extended workweek of 48 hours. For weekly hours in excess of 48 and daily hours in excess of 10, they must be paid 1.5 times the regular rate.

“Extra players” (extras in the film and television industry) who work 9 or 10 hours in a day must be paid at a rate of 1.5 times their regular wage for those hours. If they work more than 10 hours, the extra hours must be compensated at a rate of 2 times their usual wage.

Minors who work more than six days a week must be paid 1.5 times their regular wage for the seventh day of work.

For non-exempt agricultural workers, premium pay of 1.5 times the regular wage must be paid after 10 hours in any of the first six workdays in a given week, and for the first 8 hours of the seventh workday. After the first 8 hours of the seventh day, premium pay must increase to 2 times the regular wage. The seventh day overtime only applies when the hours worked in the first six days exceed 30 hours.

Live-in employees who are required to work “during the three scheduled off-duty hours that fall within the 12-hour span of work” or “during the 12 consecutive off-duty hours in a workday” must be paid 1.5 times their regular wage for those hours. If a live-in employee works more than 5 days in one week, they must be paid 1.5 times their regular wage for up to 9 hours of work on the sixth and seventh days. In excess of 9 hours on the sixth and seventh day, employees must be paid two times their regular wage.

Non-live-in employees in household occupations who are not otherwise exempt from overtime protections are not entitled to overtime on the seventh day of work, if they have worked no more than 30 hours throughout the week and no more than 6 hours per day. Otherwise, the standard rules apply.

ILLINOIS

In Illinois, the standard rule is that any work done in excess of 40 hours per week must be paid a rate of 1.5 times the regular rate of pay.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Some categories of employees are exempt from overtime rules in Illinois, including:

- Most salespeople engaged in selling cars, trucks, farm implements, trailers, boats or aircrafts

- Agricultural workers

- Executive, administrative, and professional workers

- Commissioned employees

- Employees who have temporarily exchanged hours with other employees

- Most employees of residential and childcare facilities

- Crew members of uninspected towing vessels

- Workers covered by a collective agreement

NEW YORK

In New York State, any hours worked in excess of 40 in any given week must be compensated at 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate of pay.

Exemptions: Some workers are exempt from overtime coverage, including:

- Executive, administrative, and professional employees

- Outside salespeople

- Government (federal, state, or municipal) employees

- Farm labourers

- Certain volunteers, interns, and apprentices

- Cab drivers

- Members of religious orders

- Some workers for religious or charitable organizations

- Camp counselors

- Employees of sororities, fraternities, and student or faculty associations

- Part-time babysitters

Special Situations

Special Rules: For residential (“live-in”) workers, premium pay of 1.5 times the regular rate of pay is only required for hours worked in excess of 44 in a given week.

Rest Periods and Hours Free from Work (Daily & Weekly)

CANADA

Federally regulated employees are entitled to an unpaid break of 30 minutes for every 5 consecutive hours of work. If the employer requires the employee to be “at their disposal,” the employee must be paid for the break. Employees must also be granted 8 consecutive hours of rest between shifts.

During an averaging period, hours may be scheduled and worked without regard to the normal requirement for weekly rest.

ONTARIO

Employees are entitled to a certain number of hours free from work, which are captured in the regulations relating to:

- eating periods or breaks;

- daily rest periods;

- time off between shifts and weekly or bi-weekly rest periods.

Eating Periods and Breaks: An employee must not work for more than 5 hours in a row without getting a 30-minute eating period (meal break) free from work. However, if the employer and employee agree, the eating period can be split into two eating periods within every 5 consecutive hours. Together these must total at least 30 minutes. This agreement can be oral or in writing. Meal breaks are unpaid unless the employee’s employment contract requires payment. Even if the employer pays for meal breaks, the employee must be free from work in order for the time to be considered a meal break. Meal breaks, whether paid or unpaid, are not considered hours of work, and are not counted toward overtime. Aside from these specified eating periods, employers are not required to give employees “coffee” breaks or any other kind of break. Employees who are required to remain at the workplace during a coffee break or breaks other than eating periods must be paid at least the minimum wage for that time. If an employee is free to leave the workplace, the employer does not have to pay for the time.

Daily Rest Periods: An employee must have at least 11 consecutive hours free from performing work in each “day.” Under the ESA, a “day” refers to a 24-hour period; it does not have to be a calendar day. The daily rest requirement applies even if the employer has received approval from the Ministry of Labour’s Director of Employment Standards to exceed weekly limits on hours of work. This requirement cannot be altered by a written agreement between the employer and employee. This rule does not apply to employees who are on-call and called in to work during a period when they would not normally be working.

Time Off Between Shifts: Employers must give their employees at least eight hours off work between shifts, unless the employee and employer agree in writing that the employee will receive less than eight hours off work between shifts or the total time worked on both shifts does not exceed 13 hours.

Weekly or Bi-weekly Rest Periods: Employees must receive at least 24 consecutive hours off work in each work week or 48 consecutive hours off work in every period of two consecutive work weeks.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Certain categories of workers are exempt from rules around hours of work, rest periods and breaks. Firefighters and film and television industry workers are exempt from the above rules relating to hours of work, daily rest, time off between shifts, and weekly/bi-weekly rest periods and eating periods.

Other groups exempt from rules around hours of work and eating periods include:

- Construction workers

- Superintendents, janitors and caretakers

- Ambulance drivers

- Residential care workers

- Harvesting workers

Homeworkers are also exempt from all the above rules. They can be paid minimum wage for up to 12 hours per day, but are not required to be paid more than that.

Construction workers and road maintenance workers are exempt from the rules around hours of work, daily rest periods, time off between shifts, and weekly/bi-weekly rest periods, but are covered by rules around eating periods.

Managerial and supervisory employees, likewise, are exempt from the rules around hours of work, daily rest periods, time off between shifts, and weekly/bi-weekly rest periods, but are covered by rules providing for eating periods.

Special Rules: The general weekly/bi-weekly rest period rule does not apply to residential care workers. Instead, they are entitled to at least 36 hours free from work each work week. These hours must be consecutive unless the employee consents to another arrangement. If a residential care worker consents to work during a free period, the employer must pay at least 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate for the time spent working or the hour must be added to one of the next eight 36-hour periods of free time.

If the employer and the employee agree in writing, the general daily rest period rule does not apply to public transit employees, who are instead entitled to 8 consecutive hours free from work in each day. Public transit employees are not entitled to an eating period if:

- they are working a straight shift that they have chosen to work;

- they are working a split shift that they chose to work and for which no meal break that complies with the general eating period rule is provided; or

- they have chosen to work whatever shift the employer assigns and are working either a straight shift or split shift for which no meal break that complies with the general eating period rule is provided.

UNITED KINGDOM

In the United Kingdom, employees over 18 years of age are entitled to three types of breaks: a rest break, a daily break, and a weekly rest from work. Employment contracts may offer additional entitlements to these three types of breaks beyond the minimum requirements.

Employees have the right to a rest break during working hours, which is one uninterrupted break of no less than 20 minutes if they work over six hours in a day. This rest break may be unpaid, depending on the employment contract (see Working Time Regulations, 1998). Employers have the right to determine when rest breaks shall be taken, provided that the break is taken in the middle and not at the start or end of the worker’s shift and employees are allowed to leave their workstation or desk during their rest break. If an employer requires an employee to return to work before their rest break is finished, this will not count as their rest break.

Employees are also entitled to daily and weekly breaks from work. A daily break consists of a rest period of 11 consecutive hours in each 24 hour period. A weekly break consists of either one uninterrupted 24 hour period without any work each week, or one uninterrupted 48 hour period without any work every two weeks.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Domestic workers are not entitled to rest breaks at work. Those who are not entitled to all three types of breaks include workers in the armed forces, emergency services, or police and those who are dealing with exceptional circumstances such as a disaster or catastrophe. Likewise, workers in sea transport, air or road transport, and those who work in jobs where working time is not measured and the employee is in control of determining his or her own working hours are not entitled to these three types of breaks.

Special Rules: Special rules apply to workers under 18 years of age. They have the right to a rest break of no less than 30 minutes if they work over 4.5 hours in a day. They also have the right to a rest period of 12 consecutive hours in each 24 hour period, but this may be interrupted in cases where work is broken up over the day. Lastly, workers under 18 years of age are entitled to one uninterrupted 48 hour period without any work each week.

Separate rest break rules also apply to drivers of goods-carrying vehicles (i.e., truck drivers) and passenger-carrying vehicles (i.e., bus drivers). Three sets of rules may currently apply to these drivers: EU rules, AETR rules, and GB domestic rules. The rules that apply to a driver will depend on both the country in which they are driving and the type of vehicle being driven.

In certain circumstances, workers may be entitled to compensatory rest breaks because their employer requires them to work through a rest break or rest period. A compensatory rest break is an equivalent period of rest to the one they have missed, ideally in the same day. Working Time Regulations suggest that workers should receive 90 hours of rest per week on average, when daily and weekly rest periods are combined (rest breaks are not included). Circumstances that could warrant compensatory rest breaks include the following:

- shift work when daily or weekly rest breaks cannot occur between shifts;

- when worksites are a long distance from the workers’ home;

- when work is conducted in multiple sites a far distance from each other;

- when doing surveillance or security work;

- when working in certain industries such as the postal service, retail, tourism and agriculture;

- when work is related to an exceptional event (i.e., catastrophe);

- when the job requires 24-hour staffing;

- when working on board trains in the rail industry and work is linked to ensuring trains run on time;

- when the working day is split up; or

- when there is a collective agreement that has altered or removed rest breaks for certain workers

AUSTRALIA

Australia’s National Employment Standards do not address the issue of paid and unpaid rest periods. Modern awards and enterprise agreements specify the length of any rest breaks and/or meal breaks, when they are to be taken, and any rules regarding their payment (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 139). Any applicable awards and agreements will also specify the minimum number of hours an employee is required to be away from work, as a break between shifts.

UNITED STATES

Federal law does not require that employees be given rest periods or specify the number of hours they have free from work. However, if an employer does provide short breaks (of five to 20 minutes), it is specified in federal regulations that these breaks be counted as time worked. “Bona fide meal breaks” of 30 minutes or more, where the employee is completely relieved of their duties, may be considered time off work, and therefore not compensated.

CALIFORNIA

The State of California makes provisions for meal periods, daily rest periods and weekly rest periods.

Meal Periods: The State of California requires that any employee who works a shift of more than 5 hours be provided with a 30 minute meal period. If an employee works a shift longer than 10 hours, they are also entitled to a second 30 minute meal period. However, the law states that the first meal period may be waived by mutual agreement between employee and employer in cases where the shift is more than five but less than six hours long. The second period may be waived by mutual agreement if the shift is more than 10 but less than 12 hours long. Employers do not have to pay employees for their meal periods, unless it is an “on-duty” meal period, which can occur in some circumstances in which an employee cannot reasonably be relieved of all their duties; often these apply to situations in which there are no co-workers to relieve the employee while they are on their break. In these cases, meal periods are considered regular time worked and must be paid accordingly.

Daily Rest Periods: In general, California law requires that employees be provided a 10 minute break for every four hours of work performed. This does not apply to shifts that are 3.5 hours or shorter. California also has provisions in its labor code providing for the accommodation of lactation. That is, women are entitled to breaks to pump breast milk when they require it. Normally this is expected to be done concurrently with regular rest periods, but if additional time is required it may be considered time away from work and therefore not paid.

Weekly Rest Periods: According to the California Labor Code, “every person employed in any occupation is entitled to one day’s rest therefrom in seven.” In other words, workers can be required to work a maximum of six days per week. This does not apply to workers who work fewer than 30 hours per week, or fewer than six hours a day.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Only “non-exempt” employees are entitled to meal periods and daily rest periods. There are 6 categories of exemption:

- Executive

- Administrative

- Professional

- Computer professional

- Salesperson

- Artist

Furthermore, certain groups of workers are exempt from meal period rules, if they have a collective agreement that stipulates working conditions, including meal periods, including:

- Construction workers

- Commercial drivers

- Security officers

- Employees of electrical or gas companies, or any other public utility

The ‘one day of rest in seven’ rule (weekly rest period) does not apply to cases of work performed in an emergency. It also does not apply to work performed “in the protection of life or property from loss or destruction.” Additionally, the law states that “any common carrier engaged in or connected with the movement of trains” is exempt from this protection.

Special Rules: A special rule exists for employees in the motion picture industry. For these workers, there is a 6-hour shift threshold, after which they are entitled to a meal break between 30 and 60 minutes in length. A second meal break must be provided no later than six hours after the end of the previous meal period. As well, according to Order 12-2001, employees in the motion picture industry who are swimming, dancing, skating, or performing other strenuous activity “shall have additional interim rest periods during periods of actual rehearsal or shooting.”

Employees who are directly responsible for 24 hour residential care of children, the elderly, the blind, or persons with disabilities may be required to work for longer than 4 hours without being provided a rest period. However, when this occurs, it is the employer’s duty to provide an alternative rest period at another time.

On-site workers in the construction, drilling, logging, and mining industries can legally be required to stagger their rest periods, in order to prevent disrupting the flow of work. This means that an employee’s break may occur after the normal 4-hour mark. However, employers are required to provide the appropriate number of breaks per shift. Crew members on commercial passenger fishing boats on overnight trips have additional rest periods guaranteed. They are entitled to at least eight hours off for every 24 hour period, in addition to regular break and meal periods.

ILLINOIS

The State of Illinois makes provisions for meal periods and weekly rest periods.

Meal Periods: Any employee who works a shift of 7.5 hours or more must be provided a meal break of at least 20 minutes, which must be taken within the first five hours of the shift.

Weekly Rest Periods: Illinois law requires that all employees be provided 24 consecutive hours of rest in every calendar week. This is set out in the One Day of Rest in Seven Act, as well as in the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights Act. This applies broadly to employees who work more than 20 hours per week.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The meal periods rule does not apply to workers who have their meal breaks determined through a collective agreement. It also does not apply to employees who monitor individuals with mental illness or developmental disabilities and are required to be on-call throughout their entire 8-hour shift. However, these employees are entitled to eat a meal while on duty.

The One Day of Rest in Seven rule does not apply to work performed in emergency situations: in cases of machinery or equipment breakdown or other situation requiring immediate service, it is not illegal to require a worker to work more than six days in one week.

Individuals working in agriculture, coal mining, seasonal canning, and processing of agricultural products or in the security industry are also exempt from the One Day of Rest in Seven rule. There are also exemptions for employees working in a bona fide administrative, professional, and executive capacity. Furthermore, crew members of uninspected towing vessels are not afforded this right.

Special Rules: Hotel room attendants working in counties with a population of 3,000,000 or more have special provisions. They are entitled to two 15-minute paid rest periods and one 30-minute meal period for every shift of seven hours.

NEW YORK

The State of New York makes provisions for meal periods and weekly rest periods.

Meal Periods: Workers in New York State are entitled to a break for meals during their regular workday, in which they are completely relieved of their duties. The length of the break depends on their regular hours and the industry in which they work. Table 1 describes the rules that exist.

Table 1: Meal Period Requirements in New York State

|

Industry/Occupation/Hours |

Meal Period Requirements |

|

Factory workers |

60 minutes for “noonday meal” |

|

Other workers, with a day-time shift of at least 6 hours |

30 minutes, to be taken between 11am and 2pm |

|

Any worker with a shift starting before 11am and ending after 7pm |

An additional 20-minute meal period between 5pm and 7pm |

|

Factory workers with a shift of at least 6 hours that starts between 1pm and 6am |

60 minutes at a midway point throughout the shift |

|

Other workers with a shift of at least 6 hours that starts between 1pm and 6am |

45 minutes at a midway point throughout the shift |

Weekly Rest Periods: Most employees in New York State are entitled to 24 consecutive hours off work in every seven days.

Special Situations

Special Rules: When only one employee is on duty during a shift, it is considered acceptable that the employee not be completely relieved of their duties during meal periods, as long as he or she has voluntarily agreed to this. Furthermore, in special circumstances, employers can apply for a permit to provide only a 20 minute meal break. However, this permit will only be issued after the Department of Labor has investigated the request.

Exemptions: There are a number of groups who are exempt from the weekly rest period requirements, including:

- Foremen in charge

- Employees in the dairy industry in workplaces where fewer than seven people are employed

- Employees engaged in an industrial or manufacturing process that is necessarily continuous (only upon approval by the department and only in cases where employees do not work more than 8 hours per day)

- Employees who work on Sundays for a maximum of three hours setting sponges in bakeries, caring for live animals, maintaining fires, or repairing boilers or machinery

- Employees in resorts, or seasonal hotels and restaurants in small communities

- Employees in dry dock plants who repair ships

Demonstration

Overtime

As we learned in this module, overtime provisions are a means through which governments regulate working time. Although overtime thresholds and overtime pay entitlement vary by jurisdiction, overtime regulations are guided by the same general principle: limiting employers’ reliance on long, unsocial working hours. For example, requiring that employers pay a premium – commonly 1.5 times a worker’s base rate of pay – for hours worked beyond the overtime threshold is meant to discourage excessive use of overtime. This short demonstration will show how researchers can use the ESD to study overtime compensation across the jurisdictions covered by the surveys.

Note that this demonstration assumes that you are familiar with the basics of manipulating tables in the statistics database. If you are unsure how to choose which variables to display, remove variables or items from tables, modify the table layout, calculate percentages, etc., please see our tutorial on using the statistics database and/or review the demonstrations for other modules.

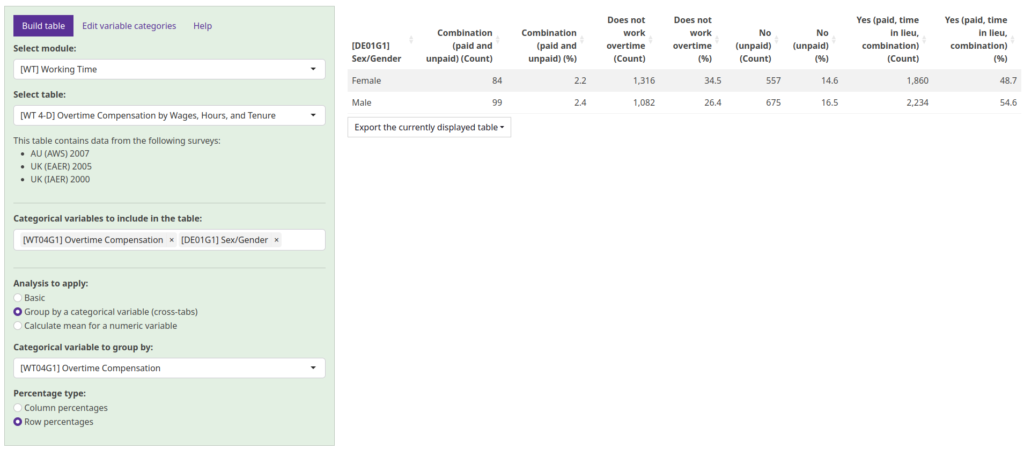

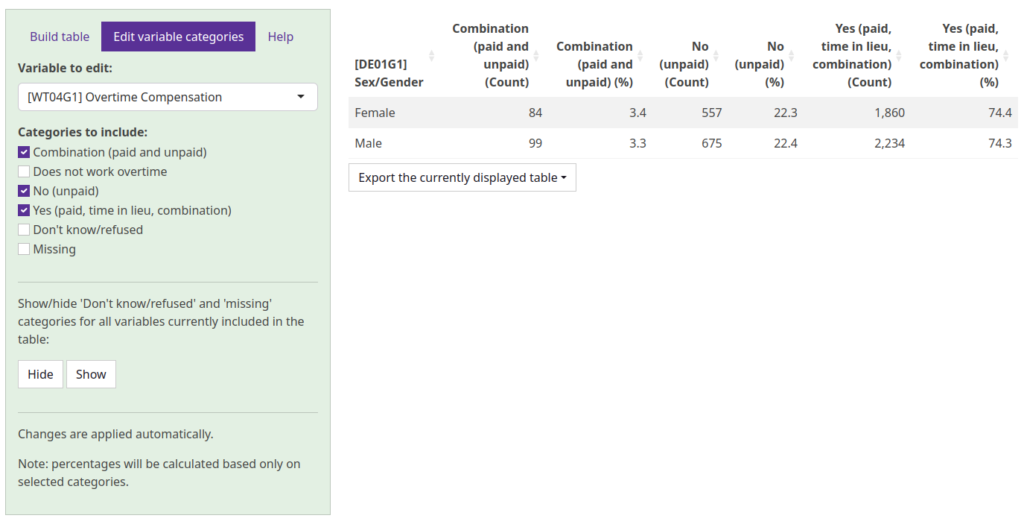

First, we can look at how overtime work and pay are distributed by gender. Drawing on data from the AWS, IAER and EAER surveys, Table 1 explores overtime work and compensation, comparing male and female respondents.

As the data demonstrate, male respondents were more slightly more likely to have worked overtime hours: 26.4% of male respondents reported not working overtime, as compared to 34.5% of female respondents. However, as shown in Table 1b, when we look just at respondents who reported working overtime, men and women are paid for that overtime at approximately the same frequency (74.4% of women report receiving overtime pay, and 74.3% of men do).

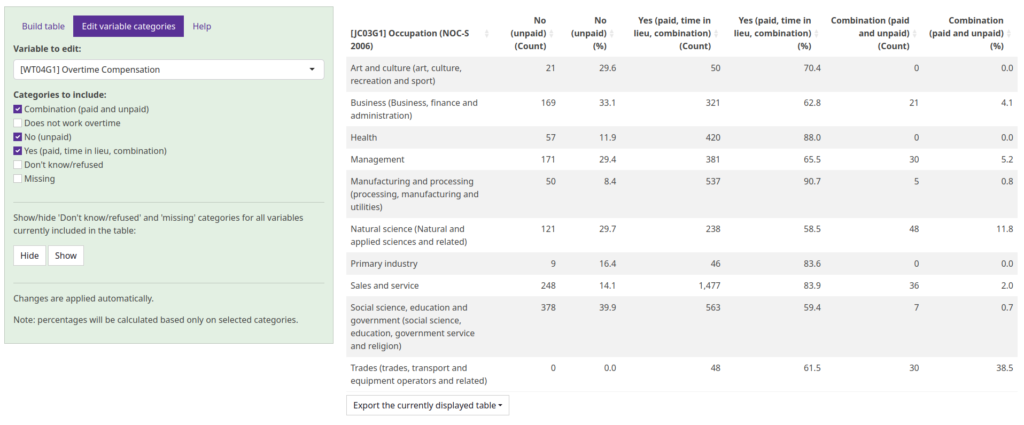

Next, we might consider which industries are more likely to have employees working overtime.

According to Table 2a, while a majority of respondents in all industries report working overtime, those in “utilities” were most likely to report that they worked overtime (only 22.1% report not doing so), followed by those in “manufacturing” (only 22.6% report not doing so).

To identify which industries are more likely to have employees working unpaid overtime, we consider Table 2b, where we have included only respondents who report work overtime.

According to Table 2b, respondents working in education are the group that most frequently reports not being paid for overtime work (nearly half, 48.2%), whereas those in the health sector are the group that least frequently reports not being paid for overtime work (13.8%).

Researchers can further explore issues related to working hours and overtime hours and compensation by searching terms such as “overtime,” “overtime pay” and “breaks” in the thesaurus and library resources, and by reviewing other secondary literature cited in this module. To read more about how to use all of the databases, please see the following tutorials:

Works Cited

Lee, S., McCann, D., & Messenger, J. C. (2007). Working Time Around the World. London, UK: Routledge.

Fudge, J. (1991). “Reconceiving Employment Standards Legislation: Labour Law’s Little Sister and the Feminization of Labour.” Journal of Law and Social Policy, 7(1), 73-89.

Thomas, M. (2004). “Setting the Minimum: Ontario’s Employment Standards in the Postwar Years, 1944-1968.” Labour/Le Travil, 54(Fall), 49-82.

Thomas, M. (2007). “Toyotaism Meets the 60-hour Work Week: Coercion, Consent, and the Regulation of Working Time.” Studies in Political Economy, 80(1), 105-128.

Tucker, E. (1990). Administering Danger in the Workplace: The Law and Politics of Occupational Health and Safety. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Vosko, L. F. (2010). Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.