Leaves, vacation and holidays

LEAVES, VACATION AND HOLIDAYS

Contents

This module provides researchers with information about the operation of employment standards related to holidays, vacation, and leaves across different jurisdictions. It also gives researchers access to data for exploring how access to different forms of leaves vary by jurisdiction and by employees’ social location. The module is organized around two key research questions:

- How have the concepts of public holiday, annual vacation, personal leave, and parental leave been developed and how have they changed across the national and sub-national jurisdictions?

- How are the features of public holiday, annual vacation, personal leave, and parental leave related to employees’ socio-demographic characteristics (e.g., social relations of gender, migration status, and employment status)?

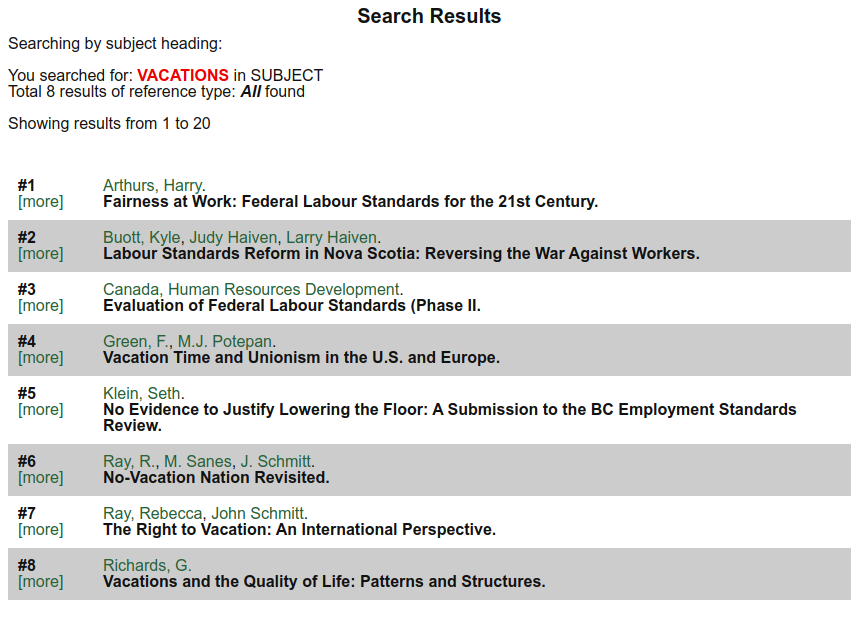

This module is comprised of an introduction to the ESD’s organizing themes and concepts surrounding holidays, vacation, and leaves, as well as a description of the indicators devised on the basis of legislative details governing statutory holidays and vacation and personal leaves in the jurisdictions covered by the ESD. The module also includes statistical tables incorporating survey data, a searchable library of published and unpublished papers, books and other resources, and a thesaurus of terms. These elements seek to provide a package of conceptual tools and guidelines for research.

KEY CONCEPTS

Public Holidays

Public holidays, also known as statutory holidays, are designated as non-working days for most employees. They are legislated at the national, provincial/state, and territorial levels, usually for cultural, civic, or religious reasons. In Canada, the Canada Labour Code (CLC) Part III and, in Ontario, the provincial jurisdiction of central focus in this database, the Ontario Employment Standards Act (ESA) establish nine statutory holidays each, with slight differences between them. The UK, in contrast, refers to public holidays as bank holidays, which differ between England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Statutory holidays are granted to most employees; exemptions and special rules may exist for employees in certain workplaces or industries (Ray, Sanes, & Schmitt 2013).

Annual Vacations

Annual vacations, also referred to as annual leaves, are authorized periods of leaves during which an employee may or may not be monetarily compensated. They are granted to an employee without restriction as to how the employee may choose to use the time. Although most jurisdictions mandate a minimum amount of vacation for employees, it is important to note that annual vacation is not recognized as an employee’s right in some countries. For example, while Australia passed legislation in 2010 that permits full and part-time employees to take 4 weeks of paid annual vacation per year (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 87), the United States lacks legislation mandating annual vacations for employees. In addition, access to annual vacation reflects the superior protection afforded to workers in a standard employment relationship. In many jurisdictions, such as Ontario, entitlement to vacation is established only after a minimum period of job tenure. Many employees in temporary employment, a form of so-called “non-standard employment,” do not accumulate sufficient job tenure to access vacation rights.

In many industrial countries paid vacation is a labour right (most readily accessible to workers in a standard employment relationship). North American employees commonly receive 2 weeks of paid vacation each year. However, their European counterparts, particularly in Northern Europe, enjoy vacation entitlements that average more than twice this amount (Green & Potepan, 1998). Scholars advance a range of explanations for the stark difference between vacation entitlements in Europe and North America. Some attribute these noticeable differences to the structure, size, and influence of organized labour in different countries (Green & Potepan, 1988). Others refer to social and cultural factors to explain the wide gap between vacation entitlements in North American and European countries. For instance, compared to Europeans, North Americans may be more likely to invest productivity and wealth in consumption rather than leisure time (Schor, 1991, as cited in Richards, 1999). Nonetheless, the development of vacation entitlements in North America and Europe has followed distinct historical trajectories.

In Europe, vacation entitlements emerged in three stages. First, before World War I, European employers had complete and exclusive control over granting vacation time. As a result, most manual labourers did not receive vacations (Richards, 1999). Second, with the growth of organized labour movements in the inter-war period, paid vacations became a key demand, and eventually became established as a common labour right. Following these two earlier developments, during the period of prolonged economic growth after World War II, vacation rights were consolidated, and in many cases, expanded. Paid vacation time became a legislated standard in many European countries (Richards, 1999). In most cases, legislation establishing paid vacation followed the strong demands of labour movements (Green & Potepan, 1988). Despite other notable achievements, the United States failed to enact legislation that would provide employees the right to paid vacation. Before World War Two, American employers strategically used paid vacation to increase employees’ productivity. In the context of mass unionization in the 1930s, employers offered paid vacation as a means of winning employees’ loyalty against unionization efforts. For this reason, although paid vacation was not a central demand of the American labour movement, some vacation time became a common feature of employment among non-unionized employees. Given this trajectory, collective bargaining for vacation in the US began considerably later than in Europe (Green & Potepan, 1988).

Leaves of Absence

A leave of absence is a period of time during which an employee is not actively engaged in their occupation; however, they are still recognized as an employee of the company. There are many different types of leaves of absence, and depending on the legislation in a jurisdiction, and different employer policies, they may be paid or unpaid.

Personal leaves were originally intended for employees to be able to take time off from work should they need to care for themselves. Personal leaves generally include sick leave, personal emergency leave, bereavement leave, and family medical leave. In Canada, employees continue to accrue pension, health and disability, and seniority entitlements while on these specific types of leaves.

Parental leave (including adoption leave) is paid leave that an employee is entitled to in order to care for their newborn or recently adopted child. Parental leaves allow for both parents to provide care for the newborn at such a crucial stage of life, and to be involved in the childrearing process. The length of time allocated for parental leaves are different depending on the legislation of the province, territory, state, or country. Whereas maternity and paternity leaves are respectively exclusive to the mother or father, mothers and fathers should have equal access to parental leaves. This leave is considered either a non-transferable individual right, or a family right that parents can divide between themselves as they choose.

Some jurisdictions treat parental leave entitlements as an entire family right, while others split the parental leave into an individual right and a familial right. In Canada’s federal jurisdiction, single employees are entitled to up to 63 weeks of job-protected parental leave. If parental leave is taken by both parents, they may use up to a combined total of 71 weeks, provided both parents work for employers who fall under the federal jurisdiction governed by the Canada Labour Code. The total duration of maternity and parental leaves in Canada’s federal jurisdiction cannot exceed 86 weeks. In Ontario, new parents have the right to take parental leave when a baby or child is born or first comes into their care. Birth mothers who took pregnancy leave are entitled to up to 61 weeks’ leave. Birth mothers who do not take pregnancy leave and all other new parents are entitled to up to 63 weeks’ parental leave. It is important to note that maternity and parental leave entitlements in Canada’s federal jurisdiction and in Ontario stipulate only the “job-protected” aspect of these leaves. Canada’s Employment Insurance program pays employees’ wage replacement. The number of weeks of monetary entitlement under employment insurance may not match the number of weeks of job-protected leave.

It is widely held that countries of greater affluence provide more support to working parents by providing them with a variety of leaves of absence that they are entitled to and encouraged to take. In the United Kingdom, a variety of legislation governs the right to maternity, paternity, shared parental, and adoption leave including the Employment Rights Act 1996 and the Employment Relations Act 1999. Statutory maternity leave in the UK is 52 weeks long and consists of ordinary maternity leave (the first 26 weeks) and additional maternity leave (the second 26 weeks). Some jurisdictions even provide working parents the option to take a leave to care for a child who is ill, as is the case in Ontario, Canada where the Ministry of Labour identifies “Critical illness leave” and “Crime-related child death or disappearance leave” as types of leaves to which employees are entitled. Entitlement to leaves to care for ill children varies significantly between jurisdictions in terms of the length of the leave, age of the child suffering illness, and payment or compensation the employee receives during the leave. Overall, leaves of absence are a large, diverse, and still evolving group of employee entitlements.

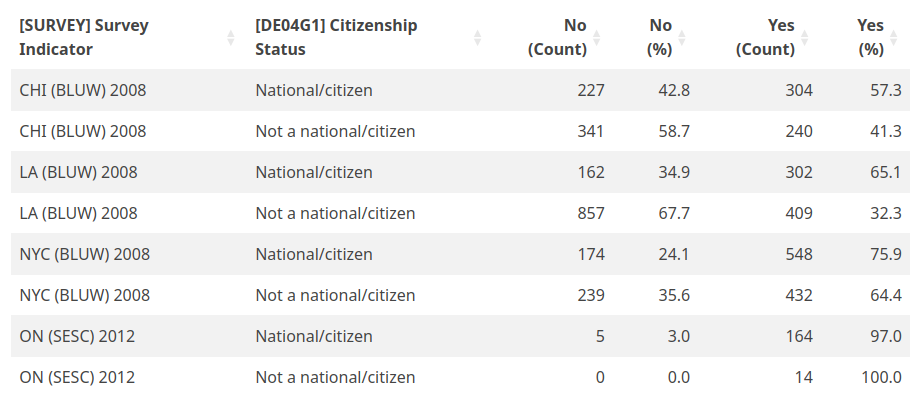

Leaves are not equally accessible to all employees. In addition to significant cross-national variations, employees’ entitlement and access to leaves within different countries reflects the ways in which superior protections are available to workers in a standard employment relationship. For example, in Australia, access to leaves is greater for men, full-time employees, permanent employees, public sector employees, trade union members, higher paid employees, and managers and professionals. Furthermore, in Australia access to leaves is more common in some sectors, such as mining, utility, government administration, manufacturing, and education (Burgess & Baird, 2003). In certain instances, access to leaves depends on conditions that indirectly disadvantage groups of employees. For example, access to some leaves requires specific durations of continuous service, but since women are more likely to take career breaks for child bearing and rearing, requirements of continuous service make some leave benefits less accessible to women. Moreover, the majority of leave benefits cannot be transferred by employees to new employment settings. The non-transferable nature of leaves also disproportionally disadvantages women because they are more likely to work in industries that commonly offer short-term employment (Burgess & Baird, 2003).

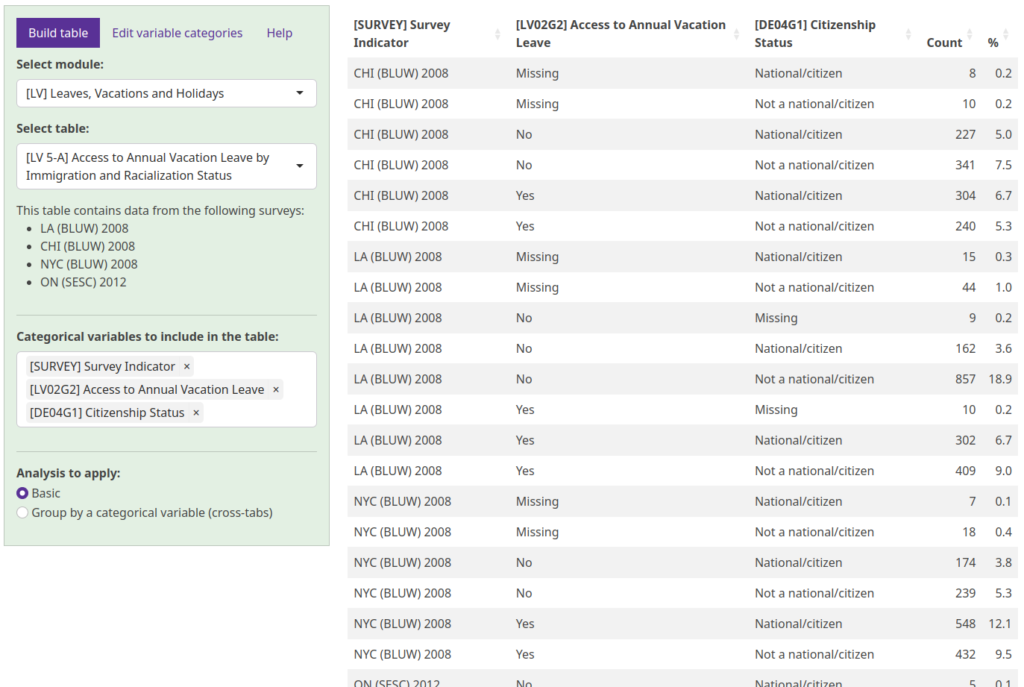

INDICATORS

The key indicators in this module can be divided into two groups: “Statutory Holidays and Vacation” and “Leaves of Absence”. The goal of these measures is to capture the degree to which survey respondents are entitled to public holiday and vacation leaves as well as personal and parental leaves. Taken together, these groups of indicators classify survey respondents into different categories given whether they are covered, exempted, or laws do not apply for the entitlement to holidays, vacation, and leaves. These indicators also measure whether survey respondents can access public holidays, vacation, and leaves in their workplace. Ultimately, these indicators can be used to understand the nature of entitlement and access to leaves across different jurisdictions in Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

The first group of variables examines the entitlement and access to public holidays and annual vacation (LV1G1; LV1G2; LV2G1; LV2G2).

Detailed information on regulations in different jurisdictions in this module provides guidance for understanding the national contexts of employment standards related to statutory holidays, vacations, and leaves.

JURISDICTION MAPPING INFORMATION

Public Holiday

CANADA

Basic Standard: Employees in Canada’s federal jurisdiction are entitled to 10 general public holidays with pay each year: New Year’s Day, Good Friday, Victoria Day, Canada Day, Labour Day, National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Thanksgiving Day, Remembrance Day, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day.

General holiday pay is equal to at least one twentieth of the wages, excluding overtime pay, that an employee earned in the four-week period immediately preceding the week in which the general holiday occurs. Different calculation methods apply in the long-shoring industry, for employees on commission, in continuous operation businesses, and for managerial and professional employees.

As of September 1, 2019 employees are entitled to holiday pay from the start of employment, eliminating the previous 30 day employment eligibility requirement.

If New Year’s Day, Canada Day, Remembrance Day, Christmas Day, or Boxing Day falls on a Sunday or Saturday that is a non-working day for an employee, the employee is entitled to a holiday with pay on the working day immediately preceding or following the general holiday. If one of the other general holidays not listed above falls on a non-working day, then a holiday with pay may be added to the employee’s annual vacation or granted at another mutually convenient time.

ONTARIO

Basic Standard: Ontario has 9 public holidays: New Year’s Day, Family Day, Good Friday, Victoria Day, Canada Day, Labour Day, Thanksgiving Day, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day. Most employees who qualify are entitled to take these days off work and be paid public holiday pay. Alternatively, the employee can agree in writing to work on the holiday and be paid:

- public holiday pay plus premium pay for all hours worked on the public holiday and not receive another day off (called a “substitute” holiday); or

- be paid their regular wages for all hours worked on the public holiday and receive another substitute holiday for which they must be paid public holiday pay

Employees are entitled to public holidays and to public holiday pay whether they are full-time, part-time, permanent or on term contract. It does not matter how recently they were hired, or how many days they worked before the public holiday. Most employees who fail to qualify for the public holiday entitlement are still entitled to be paid premium pay for every hour they work on the holiday.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Many groups of employees are exempt from the public holiday provisions of the Ontario ESA. These include firefighters, taxi drivers, farm employees, fishers, landscape gardeners, residential building superintendents, janitors and caretakers, real estate salespersons and brokers, among others.

Special Rules: Some employees may be required to work on a public holiday, including employees who work in hospitals and nursing homes and employees in continuous operations (which are operations, or parts of operations, that either never stop or do not stop more than once a week — such as an oil refinery, alarm-monitoring company, or the games part of a casino if the games tables are open around the clock). Harvesters are only entitled to public holidays and public holiday pay if they have been employed by the same employer for at least 13 consecutive weeks. Employees in the aforementioned groups can be required to work on a public holiday without their agreement, but only if the holiday falls on a day that the employee would normally work and the employee is not on vacation. If an employee is required to work on a public holiday, he or she is entitled to either: his or her regular rate for the hours worked on the public holiday, plus a substitute day off work with public holiday pay; OR public holiday pay plus premium pay for each hour worked on the public holiday. The employer chooses which of these options will apply. The employer’s ability to require employees to work on a public holiday is subject to the employee’s right to take a day off for purposes of religious observance under the Ontario Human Rights Code, and to the terms of the employee’s employment contract.

Certain retail workers who work in continuous operations (e.g., a 24-hour convenience store) have the right to refuse to work on a public holiday because of the special rules that apply to some retail workers. Where the public holiday falls on a day that would not ordinarily be a working day, or the employee is on vacation, most retail employees qualify for a substitute day off with public holiday pay. Retail businesses are excluded from these provisions if their main business is: selling prepared meals (e.g., restaurants, cafeterias, cafés); renting living accommodations (e.g., hotels, tourist resorts, camps, inns); providing educational, recreational, or amusement services to the public (e.g., museums, art galleries, sports stadiums, theatres, bars, nightclubs); selling goods and services that are secondary to the businesses described above and are located on the same premises (e.g., museum gift shops, souvenir shops in sports stadiums).

Construction employees, including road construction employees, road maintenance workers, and sewer and water main construction workers are not entitled to public holidays or public holiday pay if they receive 7.7% or more of their hourly wages for vacation or holiday pay.

Hospitality industry employees (who work in hotels, motels and tourist resorts, restaurants and taverns) may be required to work on a public holiday if the day on which the holiday falls is normally a working day for the employee and the employee is not on vacation on that day. If the employee is required to work on a public holiday, the employer may either pay the employee his or her regular rate for the hours worked on the public holiday and provide a substitute day off work with public holiday pay; or, pay the employee public holiday pay plus premium pay for each hour worked on the public holiday. Where hospitality industry employees are provided with room and board and work no more than 16 weeks in a calendar year for the employer, they are not entitled to public holidays or public holiday pay. These special rules concerning public holidays apply to any employee working in a hotel, motel, tourist resort, restaurant, or tavern even if the employee is not employed by the owner or operator of the hotel, motel, tourist resort, restaurant, or tavern.

Although the public holiday provisions of the ESA apply to assignment employees of temporary help agencies, there is a special rule that applies where a public holiday falls on a day that is not ordinarily a working day for an employee and the employee is not on assignment on that day. In that case, the employee is treated as being on lay-off, which means that he or she will be entitled to public holiday pay for the day but will have no other entitlement under the public holiday provisions. (This is so even if the week in which the holiday fell would not be considered to be a week of lay-off for purposes of the notice of termination and severance pay rules that apply to temporary help agency assignment employees.)

UNITED KINGDOM

Basic Standard: Public holidays in the UK are referred to as bank holidays. The specific holidays differ somewhat between England and Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland. Employees do not have a legal right to paid leave on bank holidays. Any right to paid time off on bank holidays will be indicated in the employment contract and it will count towards an employee’s statutory annual leave. If the place of employment is closed on a bank holiday, the employer has the right to decide if the employee must take the day off as part of their annual paid vacation entitlement.

AUSTRALIA

Basic Standard: Australia has 8 national public holidays, namely: New Year’s Day, Australia Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, Anzac Day, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day. State and territory governments may also separately declare additional public holidays such as the Queen’s Birthday and Labour Day.

All employees in Australia are covered by the National Employment Standards, which outlines the above-mentioned public holidays, including those declared by state or territory governments.

According to Australia’s National Employment Standards, most employees are entitled to take a paid day (or part day) off work on public holidays. Full and part-time employees who would normally work on a public holiday are entitled to be paid their base rate of pay, for their ordinary hours of work, and take the day off. If an employee does not have ordinary hours of work on the public holiday (for instance, if they are a casual or part-time employee and their part-time hours would not have included the day of the week on which the holiday falls) then they are not entitled to payment for the public holiday (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 116). Casual employees are entitled to take an unpaid day off work on public holidays. Employees who are off work on their annual vacation leave or due to sick leave are still entitled to a public holiday.

Special Situations

Requirement to Work: Employers may request that an employee work on a public holiday, on the condition that the request is reasonable; the Fair Work Act 2009 (s. 114) outlines the factors used to determine what constitutes a reasonable request. Employees may also refuse a request to work on a public holiday if their refusal is reasonable. Employees covered by an award or enterprise agreement who work on a public holiday may also be entitled to additional pay (this is called a penalty rate), an extra day of annual vacation leave, or a substitute paid day off work.

UNITED STATES

There are no federal laws preventing employers from requiring their employees to work on designated federal public holidays.

CALIFORNIA

There are no laws in the State of California preventing employers from requiring employees to work on state or federal public holidays.

ILLINOIS

State of Illinois law does not prevent employers from requiring employees to work on state or federal public holidays.

NEW YORK

New York State law does not prevent employers from requiring employees to work on state or federal public holidays.

Annual vacation

CANADA

Basic Standard: An employee with fewer than five years of employment is entitled to at least two weeks of vacation annually with vacation pay of at least 4 percent of gross wages. Employees with five or more years of employment are entitled to at least three weeks of vacation annually with vacation pay of at least 6 percent of gross wages. As of September 1, 2019, employees with 10 or more years of employment are entitled to at least four weeks of vacation annually with vacation pay of at least 8 percent of gross wages. Employers are required to pay employees accumulated annual vacation pay when the employee takes vacation.

ONTARIO

Basic Standard: An employee is entitled to at least two weeks of vacation annually with vacation pay of at least 4 percent of gross wages. After six consecutive years of employment with one employer, an employee is entitled to three weeks of vacation with pay equivalent to at least 6 percent of gross wages.

If the vacation entitlement year is a standard vacation entitlement year, the employee will be entitled to a minimum of two weeks of vacation time after the 12 months following his or her date of hire and after each 12-month period thereafter. If an employer establishes an alternative vacation entitlement year, the employee will be entitled to a minimum of two weeks of vacation time after each alternative vacation entitlement year but will also be entitled to a pro-rated amount of vacation time for the stub period preceding the start of the first alternative vacation entitlement year.

Special Situations

Exemptions: Travelling salespersons, real estate salespersons and brokers, farm employees, and fishers are not entitled to the annual vacation provision of the ESA.

Special Rules: In Ontario, a special rule applies to vacation pay for harvester employees whereby they are entitled to a vacation with pay if they have been employed by the same employer for 13 weeks or more. The 13 weeks do not have to be consecutive.

UNITED KINGDOM

Basic Standard: Annual vacation rules in the UK apply to those designated as ‘workers’ or ‘employees’ under section 230 of the Employment Rights Act 1996. Generally, the term worker is a broader designation: it is greater in scope than the term employee and holds fewer rights (see Employment Rights Act, 1996, s. 230). Workers are entitled to the National Minimum Wage, protection against unlawful deductions and discrimination, statutory holiday pay, rest breaks, and protection for whistleblowing. Under some circumstances, they may be entitled to sick pay, maternity pay, paternity pay, adoption pay, and parental pay. Employees, on the other hand, are entitled to all of the preceding rights as well as sick leave, maternity leave, paternity leave, adoption leave, parental leave, protection from unlawful dismissal, the right to request flexible working, and time off for emergencies. Under Working Times Regulations 1998 (amended), most workers and employees in the UK are entitled to a statutory annual leave (also known as statutory leave entitlement) of 5.6 weeks off each year. This includes those working full and part-time, agency workers and casual workers, on a pro-rata basis. Employers may choose to offer additional leave beyond the minimum, but the rules that apply to the statutory annual leave do not necessarily apply to any additional leave. For instance, additional leave may be conditional on having worked for an organization for a certain length of time.

The number of paid days of annual leave is calculated based on the number of days a week an employee or worker would normally work. For instance, for someone that normally works five days a week, multiply this number (five) by the annual entitlement of 5.6 weeks to receive 28 paid days off. Likewise, someone that works two days a week is entitled to 11.2 paid days off. It is important to note, however, that statutory annual leave is limited to 28 paid days off, regardless of whether or not the worker or employee normally works more than five days per week.

Employers have the right to designate times when statutory leave must be taken, for instance, to close an office on a bank (public) holiday. If an employee or worker is entitled to paid time off on a bank holiday, this will count towards their statutory annual leave, unless indicated otherwise in their employment contract.

Employees and workers do not necessarily have a right to carry over any unused leave into the next year; however, an employer may agree to carry-overs in their employment contract. In either circumstance, employees and workers must take a minimum of four weeks of statutory leave within a given year. If an employee or worker is entitled to more than four weeks of holiday, then they may carry the additional leave into the following year provided that their employer agrees to it. Those who are off work due to sick leave, maternity, paternity, or adoption leave may accrue their annual leave and roll it into the following year, or they may be paid for this leave. Employees may also request to take a holiday while on sick leave.

Employers should inform all staff of the dates of the statutory leave year (i.e., if it runs from January 1 to December 31, or otherwise) and employees and workers must take their leave during that year. If employers have not indicated the statutory leave year in an employment contract, the following rules apply: if an employee started working for that employer on or before October 1, 1998, their statutory leave year begins on October 1. If an employee was hired after October 1, 1998, their statutory leave year begins on the first date of their job. If an employee is hired mid-way through a leave year, they are only entitled to a portion of their annual leave in that year, depending on how much of the leave year remains.

The amount of notice required for requesting annual leave is generally twice as long as the amount of leave days requested. For example, if an employee is requesting one day of leave they must provide a minimum of two days’ notice. Employers may decline an employee or worker’s leave request but they must provide the employee with as much notice as was requested off (i.e., three weeks of notice for three weeks of leave).

Special Situations

Exemptions: Under Working Times Regulations 1998 (amended), provisions for annual leaves and annual leave pay do not apply to those working in services such as the armed forces, the police, parts of civil protection services, and agricultural workers.

AUSTRALIA

Basic Standard: As of 2010, Australia’s National Employment Standards permit full and part-time employees in Australia to take four weeks of paid annual leave per year, based on their regular hours of work (see Fair Work Act, 2009, s. 87). Casual employees are not entitled to paid annual leave, whereas employees designated as ‘shift workers’ are entitled to 5 weeks of annual leave. Typically, employees earn one day of paid annual leave for every 13 days they work. Employees covered by an award or enterprise agreement may be entitled to additional annual leave.

Employees are not required to take annual leave each year. Any unused annual leave will roll over into the next year. Employees are entitled to be paid for all accrued leave when their employment is terminated.

Annual leave can accumulate while an employee is on paid annual leave, paid sick or carer’s leave, community service leave, or long service leave. It will not accrue when an employee is on unpaid leave for any of the following: sick or carer’s leave, parental leave, or annual leave. Annual leave will not accrue when an employee is being paid by the Australian Government’s paid parental leave scheme.

Employees and employers must come to an agreement as to when and for how long leaves may be taken; there are no set minimum or maximum for leaves. Annual leave may be taken at any time provided that an employer agrees to the leave dates requested by the employee. An employer may refuse to grant annual leave only if the request is deemed unreasonable.

Employees not covered by an award or annual agreement may come to an agreement with their employer to cash out a portion of their annual leave, provided that the employee retains a minimum of four weeks of annual leave, there is a signed written agreement on each occasion that leave is cashed out indicating the amount paid and on what date, and the payment matches what the employee would have received had they taken their leave. Employees are not required to cash out any portion of their annual leave if they do not choose to.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The Fair Work Act of 2009 outlines Australia’s National Employment Standards and these standards apply to all national workplace relations system employees. Workers not covered by the national workplace relations system are instead covered by applicable state-level industrial relations systems. These include: employees in the state public sector in Tasmania, employees in the state public sector or local government in New South Wales, Queensland or South Australia, and employees in the state public sector or a non-constitutional corporation in either the local government or private industry in Western Australia. In these cases, only the state system would apply. For instance, the Government of Western Australia has its own state system which applies to employees of businesses that are sole traders, unincorporated partnerships, unincorporated trust agreements and some incorporated associations.

UNITED STATES

The federal government does not provide any legislation on how much vacation time employers must provide annually, nor does it require that vacation time be provided at all.

CALIFORNIA

California does not legally require that employers provide any vacation time to employees, paid or unpaid (State of California, “Vacation”).

ILLINOIS

Illinois does not have legislation requiring employers to provide vacation time to employees.

NEW YORK

New York State does not legally require that employers provide vacation time to employees.

Personal Leave

CANADA

At the federal level, employees have access to various paid and unpaid leave entitlements. For each of these leaves, pension, health and disability benefits, and seniority continue to accrue during an employee’s absence. The employer must continue to pay the same share of contributions as if the employee were not on leave, provided the employee makes the required contributions. If the employee does not make the required contributions, the employer is not obliged to pay the employer’s portion.

Medical Leave with Pay: After 30 days of continuous employment, all employees are entitled to 3 days of paid medical leave. At the beginning of each subsequent month, the employee receives an additional day of paid medical leave, up to a maximum of 10 days per year. Each day of paid medical leave an employee does not use in a calendar year can be carried forward to the following January. However, no employee can accrue more than 10 days of paid leave.

Personal Leave: The Canada Labour Code provides five job-protected personal leave days (the first three of which are paid) for carry out responsibilities related to care or health of family members or addressing an urgent matter concerning themselves or family members. Notes, that employees may not use personal leave for sick days. Employees who have completed three consecutive months of employment with the same employer are entitled to personal leave days.

Medical Leave: All employees are entitled to up to 27 weeks of unpaid, job-protected medical leave for illness or injury, organ or tissue donation, or medical appointments. Employees are entitled to this leave from their date of first employment.

Bereavement Leave: All employees without exception are entitled to paid bereavement leave for the death of a member of their immediate family of up to three working days within the 3-day period immediately following the day the death occurred. Employees who have completed three consecutive months of employment with the same employer are entitled to paid bereavement leave.

Compassionate Care Leave: Compassionate care leave of up to 28 weeks can be taken within a 52-week period to provide care and support to a gravely ill family member who faces a significant risk of death within 26 weeks. It is available to all employees. The entitlement of 28 weeks of compassionate care leave may be shared by two or more employees who are under federal jurisdiction. The total amount of leave that may be taken by two or more employees in regard to the same family member is 28 weeks in the 52-week period. The minimum period of compassionate care leave that can be taken is one week. The Code provides job security only. There is no provision for paid compassionate care leave. However, employees may be eligible for up to 26-weeks of compassionate care benefits under the Employment Insurance Act.

Leave Related to Critical Illness: An employee whose child is under 18 years of age and is critically ill is eligible to take up to 37 weeks of leave to provide care or support to their child. A “critically ill child” is a person under 18 years of age, on the day the leave begins, whose health has changed and whose life is at risk as a result of an illness or injury (as defined under the Employment Insurance Regulations). If both parents are employed under federal jurisdiction, they can take leave at the same time or one after the other, as long as the combined duration of the leave does not exceed 37 weeks within a 52 week period. Additionally, an employee may take up to 17 weeks of job-protected leave to care for a critically ill adult family member. The Code provides job security only. There is no provision for paid critical illness leave. However, employees may be entitled to benefits under the Employment Insurance Act. Employees are entitled to this leave from their date of first employment.

Leave Related to Death or Disappearance: An employee, whose child is under 18 years of age and has disappeared or died as a result of a probable crime, is eligible to take up to 52 weeks of leave in the case of a missing child, and up to 104 weeks of leave if the child has died. If both parents are employed under federal jurisdiction, they can take leave at the same time, or one after the other, as long as the combined duration of the leave does not exceed 52 weeks for a missing child and 104 weeks for a child who has died. The Code provides job security only. There is no provision for paid death or disappearance leave. Some employees, however, may be entitled to financial assistance from the Federal Income Support for Parents of Murdered or Missing Children grant. Employees are entitled to this leave from their date of first employment.

Leave of Absence for Members of the Reserve Force: Employees who are reservists and who are deployed to an international operation or to an operation within Canada that is or will be providing assistance in dealing with an emergency or its aftermath (including search and rescue operations, recovery from national disasters such as flood relief, military aid following ice storms, and aircraft crash recovery) are entitled under the Canada Labour Code to unpaid leave for the time necessary to engage in that operation. In the case of an operation outside Canada, the leave would include pre-deployment and post-deployment activities that are required by the Canadian Forces in connection with that operation. In order to be eligible for reservist leave, the employee must have worked for an employer for at least 6 consecutive months.

ONTARIO

Employees in Ontario have access to various paid and unpaid leave entitlements. Employees on family caregiver leave, family medical leave, critically ill child care leave, crime-related child death or disappearance leave, and organ donor leave have the right to continue participation in certain benefit plans and continue to earn credit for length of employment, length of service, and seniority. In most cases, employees must be given their old job back at the end of their leave. An employer cannot penalize an employee in any way because the employee is or will be eligible to take any of these leaves.

Sick Leave: Most employees are entitled to up to three unpaid, job-protected sick days when they have worked for an employer for at least two consecutive weeks. These days may cover personal illness, injury, or a medical emergency.

Family Responsibility Leave: Mostemployees have the right to take up to three days of unpaid, job-protected leave each calendar year due to illness, injury or medical emergency, or other urgent matters related to certain relatives. Employees are entitled to family responsibility leave days when they have worked for an employer for at least two consecutive weeks. Leave days may be taken to care for the following family members:

- A spouse

- A parent, step-parent, foster parent, child, step-child, foster child, grandparent, step-grandparent, grandchild, or step-grandchild of the employee or the employee’s spouse

- The spouse of the employee’s child

- A brother or sister of the employee

- A relative of the employee who is dependent on the employee for care or assistance

Family Caregiver Leave: Family caregiver leave is unpaid, job-protected leave of up to eight weeks per calendar year per specified family member. Family caregiver leave may be taken to provide care or support to certain family members for whom a qualified health practitioner has issued a certificate stating that he or she has a serious medical condition. Care or support includes, but is not limited to:

- providing psychological or emotional support;

- arranging for care by a third-party provider; or

- directly providing or participating in the care of the family member.

All employees, whether full-time, part-time, permanent, or term contract, who are covered by the ESA, may be entitled to family caregiver leave. There is no requirement that an employee be employed for a particular length of time, or that the employer employ a specific number of employees for the employee to qualify for family caregiver leave.

Family Medical Leave: Family medical leave is unpaid, job-protected leave of up to 28 weeks in a 52-week period for employees with certain relatives who have a serious medical condition with a significant risk of death within a 26-week period. Aside from the length of leave, the main differences between family caregiver leave and family medical leave is that an employee is only eligible for the latter if the family member has a serious medical condition has a significant risk of death occurring within a period of 26 weeks. Also, the list of family members for whose care this leave can be taken is longer than for family caregiver leave. Employees who must be away from work temporarily to provide care to a family member who has a serious medical condition with a significant risk of death within 26 weeks may be eligible to receive six weeks of “compassionate care benefits” under the federal Employment Insurance program.

The 28 weeks of family medical leave must be shared by all employees in Ontario who take a family medical leave under the ESA to provide care or support to a specified family member. The spouses could take leave at the same time, or at different times.

Critical Illness Leave: Critical illness leave is unpaid, job-protected leave of up to 37 weeks within a 52-week period in relation to a critically ill minor, or up to 17 weeks within a 52-week period in relation to a critically ill adult family member. Critical illness leave may be taken to provide care or support to a critically ill child or adult family member of an employee for whom a qualified health practitioner has issued a certificate stating that the family member is critically ill and requires care or support for a specified period. The following people are considered “family members” for purposes of critical illness leave:

- the employee’s spouse (including same-sex spouse);

- a parent, step-parent, or foster parent of the employee or the employee’s spouse;

- a child, step-child, or foster child of the employee or the employee’s spouse;

- a brother, step-brother, sister, or step-sister of the employee;

- a grandparent or step-grandparent of the employee or of the employee’s spouse;

- a grandchild or step-grandchild of the employee or of the employee’s spouse;

- a brother-in-law, step-brother-in-law, sister-in-law, or step-sister-in-law of the employee;

- a son-in-law or daughter-in-law of the employee or of the employee’s spouse;

- an uncle or aunt of the employee or of the employee’s spouse;

- a nephew or niece of the employee or of the employee’s spouse;

- the spouse of the employee’s grandchild, uncle, aunt, nephew, or niece; or

- another person who considers the employee to be like family.

Employees who take leave from work to provide care or support to their critically ill child may be eligible to receive federal Employment Insurance (EI) benefits for up to 35 weeks. Employees who take leave to provide care or support to a critically ill adult family member may be eligible to receive up to 15 weeks in EI special benefits.

Domestic or Sexual Violence Leave: Employees who have been employed for at least 13 consecutive weeks are entitled to up to 10 days and 15 weeks in a calendar year of job-protected leave related to domestic or sexual violence. The leave can be taken when the employee or the employee’s child has experienced or been threatened with domestic or sexual violence. The first five days of leave in the calendar year are paid; the remainder are unpaid.

Crime-Related Child Disappearance Leave and Child Death Leave: The crime-related child disappearance leave and child death leave are two unpaid, job-protected leaves of absence. Both provide up to 104 weeks with respect to the crime-related disappearance or death of a child (including a step-child or foster child). Employees who have been employed by their employer for at least 6 consecutive months are entitled to these leaves if it is probable, considering the circumstances, that a child of the employee disappeared or died as a result of a crime. An employee is not entitled to either of these leaves if the employee is charged with the crime or if it is probable, considering the circumstances, that the child was a party to the crime.

The total amount of crime-related child disappearance leave or child death leave taken by one or more employees under the ESA in respect of the same disappearance or death is 104 weeks. The employees who are sharing the leave can be on leave at the same time, or at different times. The sharing requirement applies whether or not the employees work for the same employer. An employee who takes time away from work because of the crime-related death or disappearance of their child may be eligible for the Federal Income Support for Parents of Murdered or Missing Children grant.

Organ Donor Leave: Organ donor leave is unpaid, job-protected leave of up to 13 weeks, for the purpose of undergoing surgery to donate all or part of certain organs (kidney, liver, lung, pancreas, or small bowel) to a person. In some cases, organ donor leave can be extended for up to an additional 13 weeks, up to a maximum of 26 weeks in total. An employee is entitled to organ donor leave whether he or she is a full-time, part-time, permanent, or term contract employee. To qualify for organ donor leave, the employee must have been employed by his or her employer for at least 13 weeks.

Reservists Leave: Employees who are reservists and who are deployed to an international operation or to an operation within Canada that is or will be providing assistance in dealing with an emergency or its aftermath (including search and rescue operations, recovery from national disasters such as flood relief, military aid following ice storms, and aircraft crash recovery) are entitled under the ESA to unpaid leave for the time necessary to engage in that operation. In the case of an operation outside Canada, the leave would include pre-deployment and post-deployment activities that are required by the Canadian Forces in connection with that operation. In order to be eligible for reservist leave, the employee must have worked for an employer for at least 6 consecutive months.

Employees on a reservist leave are entitled to be reinstated to the same position if it still exists or to a comparable position if it does not. Seniority and length of service credits continue to accumulate during the leave.

Unlike the case with other types of leave, an employer is entitled to postpone the employee’s reinstatement for two weeks after the day on which the leave ends or one pay period, whichever is later. Also, the employer is not required to continue any benefit plans during the employee’s leave. However, if the employer postpones the employee’s reinstatement, the employer is required to pay the employer’s share of premiums for certain benefit plans related to his or her employment and allow the employee to participate in such plans for the period the return date is postponed.

Special Situations

Special Rules: White collar professionals, such as lawyers, those working in healthcare (such as nurses, medical laboratory technologists, and physicians and surgeons) may not take family responsibility leave where it would constitute an act of professional misconduct or a dereliction of professional duty.

UNITED KINGDOM

Employees in the UK have a right to take a reasonable amount of time off to deal with an emergency involving a family member or dependent. The person involved may be a spouse, a partner, a child, grandchild, parent, or a person who depends on the employee for care. Since emergencies may vary, there is no predetermined amount of time for this leave; it is situation dependent. There are no limits to the number of times personal leaves can be taken off to deal with an emergency. Incidents involving a dependent that would be classified as an emergency include: illness, injury, assault, going into labour unexpectedly, a disruption of care arrangements, or an incident involving a child during school hours. This form of leave is unpaid unless outlined otherwise in an employment contract or in an agreement with an employer. This form of leave only applies to unforeseen circumstances; it does not apply if the situation is known in advance (i.e., for a pre-arranged medical appointment). An employer may also choose to grant an employee compassionate leave in the case of an emergency, which may be paid or unpaid. An employer should be notified of an emergency as soon as possible; this does not need to be done in writing and no formal documentation is necessary.

If an employee is sick for more than seven days in a row (including non-working days) they are required to provide their employer with a sick note from a doctor. This sick note may either indicate that the employee may be fit to return to work, or not yet fit for work. Employers may also require that employees fill in a self-certification form if they have been sick for more than seven days in a row. If an employee is sick for more than four weeks they may be considered long-term sick. Long-term sick employees can ask their employer or their doctor to refer them to a Fit for Work program and can agree to a return to work plan; however, an employer can also choose to dismiss a long-term sick employee.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The emergency and sick leaves described above only apply to those designated as ‘employees’ under section 230 of the Employment Rights Act 1996. What makes employees distinct from other designations (workers, self-employed, etc.) is they hold an employment contract with their employer. This contract does not necessarily have to be in writing; the employee must simply accept their job offer (see Employment Rights Act, 1996, s. 230).

AUSTRALIA

All employees covered by the national workplace relations system in Australia are covered by the National Employment Standards, which governs paid personal/carer’s leave, unpaid carer’s leave, and paid or unpaid compassionate leave, regardless of any applicable awards, enterprise agreements, or employment contract. This includes full-time and part-time employees. Casual workers are only entitled to unpaid carer’s leave and unpaid compassionate leave. An employee may take personal/carer’s leave if they are not fit for work due to illness or injury, or because they must provide support to an immediate family member due to an illness, injury, or unexpected emergency.

Personal/carer’s leave refers to both personal sick leave and carer’s leave entitlements. Employees are entitled to a minimum of 10 paid personal/carer’s leave days per year in order to deal with personal illness, emergencies, caring responsibilities, and the death or serious illness of immediate family members. An employee’s paid personal/carer’s leave days may accumulate from one year to the next. An immediate family member of an employee may include any of the following people: a spouse or partner, a child, a grandchild, a parent, a grandparent, a sibling, or the child, parent, grandparent, grandchild, or sibling of the employee’s spouse or partner.

With respect to unpaid carer’s leave, employees are entitled to two days of unpaid leave for each incident. Unpaid leave does not accumulate from one year to the next. Employees are also entitled to two days of compassionate leave when a member of their immediate family sustains a life-threatening injury or illness, or after a death in the immediate family. For all forms of personal/carer’s leave and compassionate leave, an employer must be notified of the intent to take leave as soon as is practicable and the employer has the right to request documentation substantiating the claim to the leave.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The Fair Work Act of 2009 outlines Australia’s National Employment Standards and these standards apply to all national workplace relations system employees. Workers not covered by the national workplace relations system are instead covered by applicable state-level industrial relations systems, including,

- Employees in the state public sector in Tasmania

- Employees in the state public sector or local government in New South Wales, Queensland, or South Australia

- Employees in the state public sector or a non-constitutional corporation in either the local government or private industry in Western Australia

In these cases, only the state system would apply. For instance, the Government of Western Australia has its own state system which applies to employees of businesses that are sole traders, unincorporated partnerships, unincorporated trust agreements and some incorporated associations

UNITED STATES

While the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), 1938 does not require employers to provide personal leave to their employees, a separate piece of legislation does. The Family and Medical Leave Act 1993 allows workers to take up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave for one of the following reasons:

- to care for a newborn or newly adopted child;

- to care for an immediate family member with a serious health condition;

- when the employee is unable to work because of their own serious health condition; or

- to spend time with a family member who is on active military duty

The FMLA also allows employees to take a reduced or intermittent work schedule for the above reasons. In each case, the Family and Medical Leave Act requires that an employee on leave have any existing health benefits continue throughout their leave. They are also entitled to return to their previous job, or an “equivalent” job, when their leave is over.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The Family and Medical Leave Act only applies to employees who have been with their employer at least 12 months, and who have worked at least 1,250 hours during the previous 12 months. Therefore, employees with a shorter tenure or fewer hours are exempt from coverage. Furthermore, this coverage only applies to employees who work at locations where a minimum of 50 individuals are employed, or where at least 50 individuals are employed by the same company within 75 miles of the location.

CALIFORNIA

Several pieces of legislation govern leaves in the State of California. The California Family Rights Act is based on the federal Family and Medical Leave Act. Like the federal law, the Act entitles workers to up to 12 weeks of unpaid job-protected leave for one of the following reasons:

- the birth or adoption of a child;

- to care for an immediate family member with a serious health condition; or

- when the employee is unable to work due to their own serious health condition

Any health, dental, or vision care benefits must be maintained throughout this leave.

Since 2015, the Healthy Workplace, Healthy Family Act has required that employers provide paid sick leave to their employees. Paid sick leave accrues at the rate of one hour per 30 workdays. An employee may only take paid sick leave once they have worked 90 days for the employer. Employers are entitled to limit paid sick leaves to three days per year (or 24 hours), but an employee’s leave may carry over to the following year, up to six days (or 48 hours). The Healthy Workplace, Healthy Family Act does not apply to workers covered by a valid collective bargaining agreement.

Paid Family Leave is a program that provides six weeks of partial pay to workers who are unable to work because they are taking time off to bond with a new child (including foster and adopted children), or to care for a seriously ill family member. It is a contributory program, and thus in order to be eligible for Paid Family Leave, a worker must have contributed through payroll deductions. This leave applies to full- and part-time public and private sector employees, who have contributed to the State Disability Insurance program through mandatory payroll deductions at least once in the past 18 months. Self-employed workers may also be eligible if they have contributed to the Disability Insurance Elective Coverage Program.

Special Situations

Exemptions: The California Family Rights Act only applies to employees who have worked more than 12 months for their employer, and whose hours have totaled at least 1,250 during the previous 12 months. Thus shorter tenure or more part-time employees are exempt. Furthermore, the Act only applies to employers with 50 or more employees. Employees of small firms are exempt.

The Healthy Workplace, Healthy Family Act does not apply to In-Home Support Service providers, or certain employees of air carriers.

Anyone who has not contributed to the State Disability Insurance or the Disability Insurance Elective Coverage Program is exempt from paid family leave.

ILLINOIS

Beyond the federal laws, the State of Illinois does not have additional requirements that employers provide paid or unpaid sick leave, or leave to care for a family member. However, in cases where an employer has a sick leave policy, the Employee Sick Leave Act entitles employees to use at least a portion of their sick leave entitlement to care for immediate family members.

NEW YORK

On January 1, 2018, New York State implemented the Paid Family Leave policy. This program is mandatory for all private employers in the state, and is funded through payroll deductions. It allows eligible employees to take up to 10 weeks of paid leave a year. Employees receive 55 percent of their regular earnings up to a cap while on leave. By 2021, the maximum duration of paid leave will increase to 12 weeks.

The Paid Family Leave policy covers leaves for

- the birth or adoption of a new child;

- caring for a close relative with a serious health condition; and/or

- spending time with a relative who is on active military duty or who has an impending call to active duty.

Throughout these leaves, any employer health benefits will continue, though if the program is contributory, the employee must continue to make contributions throughout their leave. The Paid Family Leave program is mandatory for private employers. Public employers may opt in, and unionized public workers are only included if it is outlined in their collective agreement. Therefore, some public employees may not be covered.

In addition, if an employment contract (written, oral, or based on past practices) includes paid or unpaid sick leave, the employer is required by law to provide it.

Special Situations

Exemptions: In order to be eligible for paid family leave, an employee must have been employed full-time for 26 weeks, or part-time for 175 hours. Thus, new employees or shorter tenure employees will be exempt until they reach that threshold. Farm workers are exempt from the Paid Family Leave policy. Other seasonal workers may also be exempt.

New York City

New York City has a Paid Sick Leave Law, which came into effect in 2014. Employees may take sick leave for the following reasons:

- if they have a mental or physical illness, injury, or health condition;

- if they require treatment for one of the above;

- if they are seeking preventative medical care;

- if they are caring for a family member (child, grandchild, sibling, partner, parent or grandparent) satisfying any of the above conditions;

- if their employer’s business closes due to a public health emergency; or

- if they must care for a child whose school or childcare provider is closed due to a public health emergency

Typically, employees are entitled to 40 hours of paid sick leave in a calendar year. This law covers a large portion of New York City’s workers: full-time and part-time employees, transitional job program employees, undocumented workers, and employees who live both in and outside of the city (but work in New York City).

Special Situations

Exemptions: The following workers are not covered by New York’s Paid Sick Leave Law:

- Workers who work 80 or fewer hours per calendar year

- Students in federal work study programs

- Employees whose work is paid for by scholarships

- Employees of government agencies

- Independent contractors

- Participants in Work Experience Programs

- Some unionized employees

- Physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech language pathologists, and audiologists who manage their own schedules, can reject or accept any assignment referred to them, and are paid at least four times the federal minimum wage.

Special Rules: Employees of organizations that employ four or fewer employees are entitled to 40 hours of sick leave, but they are not entitled to pay for that leave.

Parental Leave

CANADA

Employees in the federal jurisdiction have access to maternity leave and parental leave. For both leaves, the employer must pay at least the same share of pension, health and disability contributions as if the employee were not on leave, unless the employee does not pay her or his contributions. Likewise, the accumulation of seniority continues during the employee’s absence.

Maternity Leave: Female employees, including managers and professionals, are entitled to maternity leave. The CLC provides for up to 17 weeks of maternity leave. The 17-week maternity leave may be taken any time during the period that begins 11 weeks before the expected date of delivery and ends 17 weeks after the actual delivery date. An employee on maternity leave is entitled to 15 weeks of Employment Insurance under the federal Employment Insurance program.

Parental Leave: Any employee who assumes actual care of a newborn or newly adopted child is entitled to parental leave of up to 63 weeks. Parental leave may be taken any time during the 52-week period starting the day the child is born or the day the child comes into the employee’s care. An employee on parental leave is entitled to 35 weeks of Employment Insurance under the federal Employment Insurance program.

Parental leave can be taken by both parents for a combined total of up to 71 weeks provided both parents work for employers who fall under the federal jurisdiction governed by the Canada Labour Code. Parents have the option of taking their parental leave at the same time, or one after the other, as long as the total combined parental leave does not exceed 71 weeks. Employees combining parental leave are entitled to 40 weeks at 55 percent of weekly earnings or 69 weeks at 33 percent of weekly earnings under the Employment Insurance program. The total duration of the maternity and the parental leaves cannot exceed 63 weeks.

Special Situations

Interruptions: If an employee’s child is hospitalized shortly after birth or adoption, with the consent of the employer, the employee can interrupt the leave and temporarily return to work. The period within which maternity leave may be taken is extended by the number of weeks the child is hospitalized. However, maternity leave must end no more than 52 weeks after the date of delivery.

It is also possible for an employee to interrupt his or her parental leave to take compassionate care leave, leave related to critical illness of a child, leave related to death or disappearance of a child, sick leave, work-related illness or injury leave, or reservist leave (except for the purposes of annual training). In such a case, parental leave resumes immediately after the other leave ends. The period within which parental leave may be taken is extended by the number of weeks during which the child is hospitalized or during which the employee takes one of the other leaves mentioned above. However, parental leave must end no later than 104 weeks after the day on which the child is born or comes into the employee’s actual care.

ONTARIO

Ontario makes provisions for pregnancy leave and parental leave. Employees on pregnancy or parental leave have the right to continue participation in certain benefit plans and continue to earn credit for length of employment, length of service, and seniority. In most cases, employees must be given their old job back at the end of their pregnancy or parental leave. An employer cannot penalize an employee in any way because the employee is or will be eligible to take a pregnancy or parental leave, or for taking or planning to take a pregnancy or parental leave.

Pregnancy Leave: Pregnant employees have the right to take pregnancy leave of up to 17 weeks of unpaid time off work. In some cases the leave may be longer. An employee is eligible for Employment Insurance for 15 of those weeks under the federal Employment Insurance program.

Parental Leave: New parents have the right to take parental leave – unpaid time off work when a baby or child is born or first comes into their care. Birth mothers who take pregnancy leave are also entitled to up to 61 weeks of parental leave. Birth mothers who do not take pregnancy leave and all other new parents are entitled to up to 63 weeks of parental leave. A new parent is eligible for Employment Insurance for 35 of those weeks under the federal Employment Insurance program, or 40 weeks if parental leave is combined.

Parental leave is not part of pregnancy leave and so a birth mother may take both pregnancy and parental leave. In addition, the right to a parental leave is independent of the right to pregnancy leave. For example, a birth father could be on parental leave at the same time the birth mother is on either pregnancy leave or parental leave.

UNITED KINGDOM

A variety of legislation governs the right to maternity, paternity, shared parental, and adoption leave in the UK, including the Employment Rights Act 1996 and the Employment Relations Act 1999, among others. Under the Equality Act (2010, sec. 18), pregnant employees are protected from discrimination or unfair dismissal. A maternity, paternity, and parental leave calculator tool for the UK is available online.

Pregnant employees have the legal right to paid time off for pre-natal care, maternity leave, and maternity pay or maternity allowance. They might also be eligible for additional government assistance in the form of benefits, tax credits, income support, and/or additional unpaid parental leave. Paid time off at the normal rate of pay must be given to pregnant employees for pre-natal care. This care can include appointments and classes recommended by a doctor or midwife. The pregnant employee’s partner, the father of the baby, or the intended parent also has the right to unpaid time off to attend two pre-natal appointments, up to 6.5 hours per appointment.

Pregnant employees are required to inform their employer about their pregnancy a minimum of 15 weeks before the beginning of the week of the baby’s due date and an employer may ask for this to be put in writing. Employees must also inform their employer of the date they intend to start their maternity leave. In cases where this isn’t possible, such as when the employee did not realize they were pregnant, they must inform their employer of the pregnancy as soon as possible. Time off for pre-natal care will only be granted once the employer is informed of the pregnancy.

Maternity Leave: Statutory maternity leave in the UK is 52 weeks long and consists of ordinary maternity leave (the first 26 weeks) and additional maternity leave (the second 26 weeks). The earliest that an employee can take maternity leave is 11 weeks prior to the week of the baby’s due date. If the baby is born earlier than expected, maternity leave must begin once the baby is born. In the case that the pregnant employee must take time off for pregnancy-related illness in the four weeks prior to their due date, maternity leave will automatically begin, regardless of any prior arrangements. Even if a pregnant employee chooses not to take maternity leave after their baby is born, they are still required to take a minimum of 2 weeks off work, or a minimum of 4 weeks off work if they work in a factory. If an employee plans to change the date for their return to work from maternity leave, they must give their employer at least eight weeks’ notice. During the period that an employee is on statutory maternity leave, their rights to accrued holidays, pay raises, and their right to return to work are protected. Employees are entitled to 39 weeks of statutory maternity pay. The first six weeks are paid at 90 percent of average weekly earnings. The remaining 33 weeks are paid at £148.68 or 90 percent of average weekly earnings, whichever is lower.

Paternity Leave: Paternity leave in the UK applies when an employee takes time off work because their partner is having a baby, having a baby through a surrogacy arrangement, or adopting a child. There are several eligibility requirements for paternity leave. As with maternity leave, only employees are eligible. Eligibility for paternity leave requires that the leave be taken to take care of the child. The employee must have worked a minimum of 26 weeks continuously prior to the end of the 15th week of the expected due date. Eligible employees may receive either one or two weeks paid paternity leave. A week refers to the normal number of days that an employee would work during a week. For instance, if the employee normally only works on Fridays, a one-week leave is equivalent to one Friday off. Paternity leave cannot begin before the birth of the child, it must be taken all at once, and it must end within 56 days of the birth of the child, except in cases of adoption. If an employee plans to change the start date of their paternity leave, they must give their employer at least 28 days of notice.

Paternity leave also requires that the employee is one of the following: the father, the child’s adopter, the husband or partner of the mother (or adopter), or the intended parent through a surrogacy arrangement. The appropriate amount of notice must also be given to the employer. Notice must include the expected due date, when you expect the paternity leave to start, and the length of the leave (it may be one or two weeks’ leave). As with maternity leave, the employer can ask for this notice to be made in writing. Paternity leave cannot be taken after shared parental leave.

Adoption Leave: In the case of adoption and surrogacy arrangements, employees may be eligible for statutory adoption leave. As with other forms of parental leave, an employee’s rights to accrued holidays, pay raises, and their right to return to work are protected while on adoption leave. In the case of fostering a child for adoption, employees may be eligible for adoption leave from the time the child comes to live in their house. Some notable exemptions exist for adoption leave. Employees who arrange a private adoption, adopt a family member or stepchild, or become a kinship carer or guardian do not qualify for adoption leave or pay.

Similar to maternity leave, adoption leave in the UK is 52 weeks long and consists of ordinary adoption leave (the first 26 weeks) and additional adoption leave (the second 26 weeks). Statutory adoption pay is also the same as statutory maternity pay. If a couple is adopting, only one person may claim adoption leave, while their partner may be eligible for paternity leave. For those who have been granted adoption leave, once matched with a child they may receive paid time off for up to 5 adoption appointments. Their partner (the secondary adopter) would be entitled to take unpaid leave for up to 2 adoption appointments. Adoption leave requires that the employer be given notice within 7 days of being matched with a child. This notice must indicate the start date and duration of the adoption leave, as well as the date of placement of the child. Employers have the right to request this notice in writing along with proof of the adoption or surrogacy. For surrogacy arrangements, employers must be informed of the expected due date and when the leave will begin a minimum of 15 weeks prior to the expected week of the child’s birth. In addition, an employer may request a notarized written statement indicating the employee’s intention of applying for a prenatal order within 6 months of the birth of the child when a surrogacy arrangement applies.

For UK-based adoptions, leave may begin no more than 14 days before the child moves in. For overseas adoptions, leave may begin on or within 28 days of the child’s arrival in the UK. For surrogacy arrangements, leave may begin on either the day the child is born or the next day. The eligibility criterion for adoption leave differs slightly for overseas adoptions and surrogacy arrangements. In the case of overseas adoptions, employees must have worked continuously for the same employer for at least 26 weeks prior to providing notice of adoption leave. If adopting the child with a partner, the employee must also provide their employer with a signed SC6 form (available from HM Revenue & Customs, the UK’s tax authority). In the case of surrogacy arrangements, the leave eligibility requirements are the same as for other adoptions; however, if the employee is genetically related to the child (for instance, if they are a sperm or egg donor), they may choose to take paternity leave instead of adoption leave; however, they may only select one.

Shared Parental Leave: Employees who are having a baby or adopting a child may also be eligible for shared parental leave and statutory shared parental pay. Shared parental leave regulations came into effect on December 1, 2014 and apply to eligible parents of babies due and children adopted on or after April 5, 2015. If both parents are eligible for shared parental leave, this leave may be shared between them and they may choose to take their leave in separate blocks of time, up to 3 blocks each, although an employer may agree to further split these blocks into shorter periods of time of a minimum of one week. Shared parental leave does not need to be taken all at once; periods of shared parental leave may be interspersed with periods of work. It may only begin once the child is born or has been placed for adoption. In order to claim shared paternal leave, an employee on maternity leave must first end that leave or end her maternity pay or allowance. Likewise, an employee or their partner on adoption leave must end their adoption leave or pay in order to claim shared paternal leave. Employees eligible for shared paternal leave and statutory shared paternal pay may choose to take their paternal leave as 52 weeks minus any adoption leave or maternity leave already claimed as well as 39 weeks of shared paternal pay minus any claimed weeks of maternity pay, maternity allowance, or adoption pay. If neither the employee nor their partner claimed maternity leave or adoption leave, then the shared parental leave will be 52 weeks long. Parents may choose how they would like to split their shared parental leave. All shared parental leave must be taken between the birth of the child and their first birthday, or within one year of adoption. If both parents are eligible for shared parental leave, they may also take their leave in separate blocks.

There are several eligibility requirements for shared parental leave. Responsibility for caring for the child must be shared between husband and wife, civil partners or joint adopters, the child’s other parent, or the parent’s partner if all are living together. One of the parents must have been eligible for (but did not necessarily need to claim) one of the following: maternity leave or pay, adoption leave or pay, or maternity allowance. Employees must have been employed continuously with that employer for a minimum of 26 weeks prior to the end of the 15th week before the expected due date of the child or the date a child is matched with a parent, in the case of adoption. Additionally, in the 66 weeks prior to the expected due date (or in the case of adoption, the week the child is matched) the partner of the employee (or child’s other parent) must have worked for at least 26 weeks (though not necessarily continuously) and earned at least a total of £390 within 13 of those 66 weeks (not necessarily in a row) as either an employee, a worker, or while self-employed.

For shared parental leave to begin, an employee must present their employer ‘binding notice’ or end their maternity or adoption leave. The partner (or the child’s other parent is on maternity leave or adoption leave) may begin shared parental leave by presenting their employers with ‘binding notice’. To apply for shared parental leave, a minimum of eight weeks’ written notice must be given to the employer indicating the dates of the leaves. Partners or the child’s other parent must also apply to their own employer in order to take shared parental leave. If requested, those applying for shared parental leave may be required to provide their employers with additional information within 14 days; this information might include things like a copy of the birth certificate, or the name and address of the partner’s employer.